Reactivity in Chemistry

Mechanisms of Glycolysis

GL9. Thermodynamics of Glycolysis: Concentrations Matter

In the last section, we looked at the energetic changes along the glycolysis pathway. The picture we got was of a hilly environment, with lots of barriers and many valleys to get stuck in. In this section, we are going to see a slightly different picture of the energetic terrain of glycolysis. Rather than the roller coaster ride we saw before, we will find that glycolysis exists mostly on an energetic plain, with just a couple of steep drops. The reason for that has to do with the relative concentrations of the different species under cellular conditions.

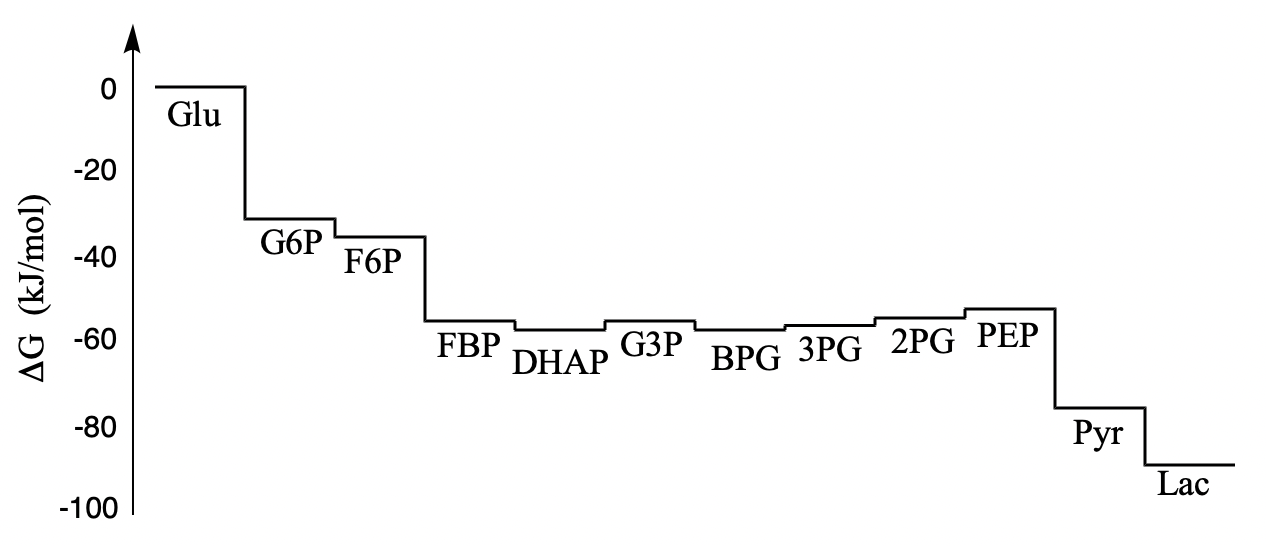

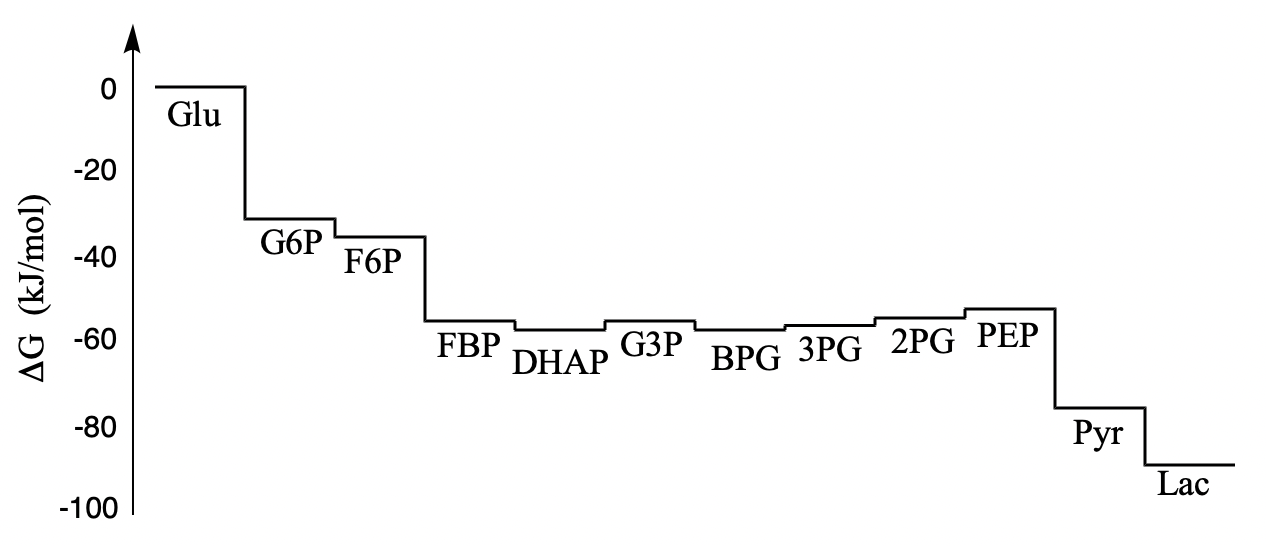

Figure GL9.1. Thermodynamic changes along the glycolysis pathway under cellular conditions.

Why is this picture different from the one we saw before? The energy map we saw earlier was based on the equilibrium constant of each reaction in the standard state. That gave us the standard free energy change for that reaction.

Here, T is the temperature in Kelvin and R is the ideal gas constant. You might know that the ideal gas constant is a statistical factor, based on Boltzmann's constant, relating temperature to available energy. You can find different values for it based on the units you are interested in working in. Most commonly, we see it expressed as R = 8.314 J K-1 mol-1.

Conditions inside the cell are not at the standard state. They are not at equilibrium, either. The cell is sometimes descibed as being in an environmental steady state. In an environmental steady state, material and energy are constantly being supplied to the system but are balanced by material and energy leaving the system, so that their levels remain somewhat steady. Thus, we have a general idea of the approximate concentrations of various compounds in the cell, even if they are constantly changing. We can correct for that difference in concentration between the standard state and the cell by a small modification of the equation for free energy.

In this case, Q has the form of the equilibrium constant, but the concentration values are whatever we happen to have under the current conditions, instead of being values at equilibrium.

We think of ΔG as the driving force to get to equilibrium. When ΔG = 0, we have reached equilibrium. Looking at the graph, we can see that, at cellular concentrations, most of the steps in glycolysis have ΔG values that are fairly small, meaning they are not that far from equilibrium. That turns out to be really important. If a reaction is already close to equilibrium, we know that it is pretty easy to shift the equilibrium one direction or the other with small changes in concentrations of the reactants or products. Add a little more reactants, and the reaction shifts forward. Add a little more products, and the reaction shifts into reverse.

The reactions of glycolysis are catalyzed by enzymes. Generally, an enzyme has no effect on the equilibrium of a reaction. The equilibrium is the same with or without the enzyme; the enzyme just makes it get there faster. Most of the time, it doesn't even matter which side of the reaction we are starting from. The enzyme just lowers the barrier for the reaction, so if it lowers the barrier for the forward reaction, it is also lowering the barrier to the reverse reaction. As a result, an enzyme can generally catalyze both the forward direction or the reverse direction of a given process. These reactions are described as being under substrate control. That means the direction of the reaction is controlled by the relative amounf of reactant and product. If the reactant concentration gets a little high, the equilibrium shifts forward. If the product concentration gets a little high, the reaction shifts backward. Substrate control is a great way for the process to self-regulate, because it can simply shift whichever direction it is needed.

There are some limitations to this idea. Suppose a reaction is very exothermic. In that case, the forward reaction is easy to do once the barrier is lowered, but the reverse reaction may still be very difficult, because it would be very endothermic. Even an enzyme may have trouble pushing this reaction backward. Some of the steps in glycolysis are not subject to substrate control, so they need other mechanisms to regulate those steps instead.

See the section on metabolic pathways at Henry Jakubowski's Biochemistry Online.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted on individual pages. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic,

Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by

Chris Schaller

is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: