Reactivity in Chemistry

Oxygen Binding & Reduction

OR4. Metal Oxos

In the previous section, we saw the Fe(IV) oxo group of Cytochrome P450 do something unusual. It grabbed a hydrogen atom from a substrate molecule. It did not take a proton. It took the hydrogen atom complete with its electron.

This type of reactivity is characteristic of radicals. Radicals are species that have unpaired electrons. Generally, but not always, they have odd numbers of electrons in their valence shells, leaving one electron without a spin partner. Having an odd number of electrons also leaves these compounds short of a full octet. From that point of view, it is easy to see the driving force for a reaction, from the point of view of the radical species.

However, this reaction is unusual. There are lots of metal oxo compounds on earth, but only some of them engage in this kind of radical behaviour. What makes some oxos different, in particular some biologically important iron oxos?

Let's take another look at that active form of the iron oxo complex in Cytochrome P450.

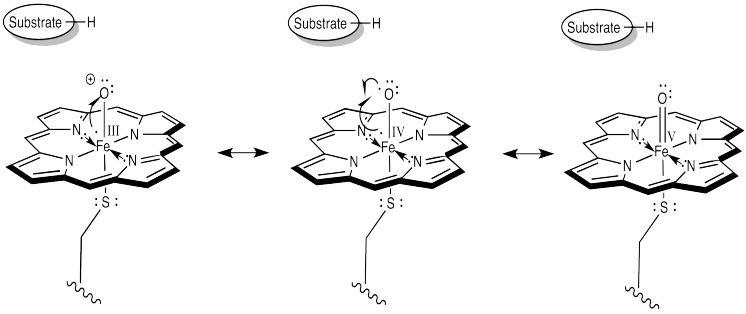

Figure OR4.1. Resonance structures of an iron oxo complex.

Earlier, we decided to think about this complex using the Fe(IV) structure. That would be a d4 iron complex. The coordination geometry appears to be octahedral. Chances are that in such a high oxidation state we would have a low-spin iron. Overall, that should give the frontier orbital diagram shown below.

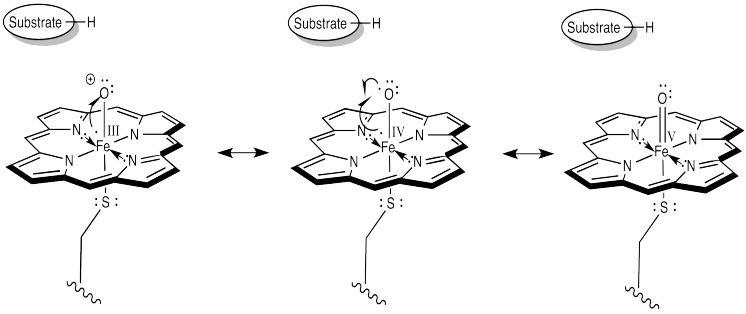

Figure OR4.2. Frontier orbitals of an iron oxo complex in an octahedral coordination environment.

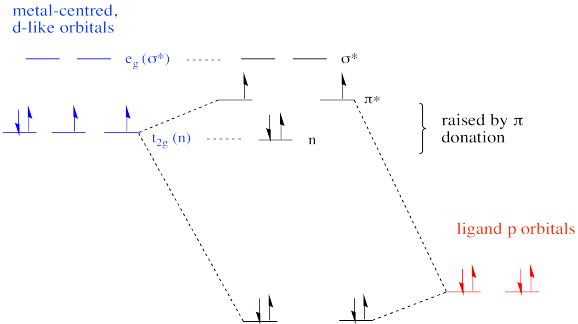

The oxo donor would have lone pairs. It would be a π donor. The same is true of the cysteine ligand trans to the oxo. We should probably modify our d orbital splitting diagram accordingly.

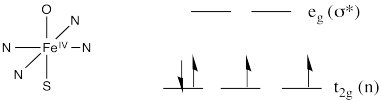

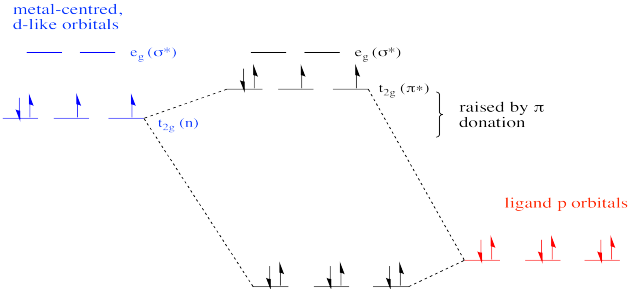

Figure OR4.3. Frontier orbitals of an iron oxo complex in an octahedral coordination environment with π-donation; the t2g set is higher in energy than before.

Remember, a π donor brings a pair of electrons from a relatively low-lying ligand orbital. The donor orbital interacts with one of the metal d orbitals that were previously non bonding. In-phase and out-of-phase combinations result. The in-phase combination is lower in energy and the out-of-phase combination is higher in energy than the levels we started with. Because the π donor is donating a lone pair, that lone pair drops in energy. It becomes a π bond. The electrons in the metal orbital involved in the interaction become anti bonding. Overall, the gap between the lower and upper d levels gets smaller.

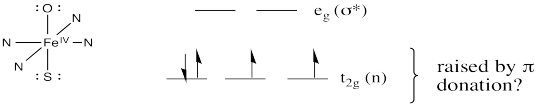

Figure OR4.4. The t2g orbitals are raised because they form the π* orbitals upon interaction with the ligands.

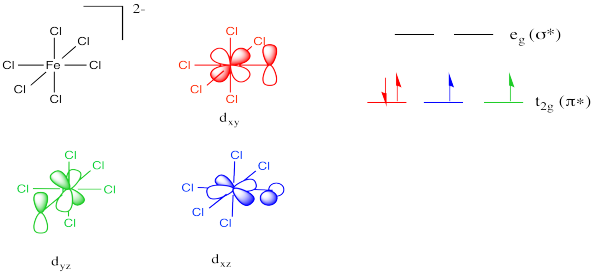

At least, that's how it would work in a normal case. In a simple example of a coordination complex, all six ligands might be the same. For example, if we had an octahedral Fe(IV) chloride complex such as FeCl62-, all six chloride ligands would be potential π donors. Different p orbitals on the chlorines would be able to interact with each of the three non bonding d orbitals, raising them all in energy via a π bonding interaction.

Figure OR4.5. The need for proper symmetry in forming π bonds between iron and chlorine.

Note the choice of different orbitals to illustrate pi donation along different axes. Not all of the t2g orbitals interact with all of the chlorine p orbitals. There is a need for symmetry matching in these interactions.

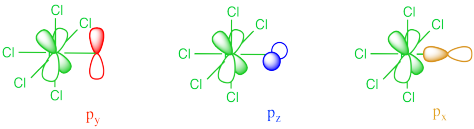

Look at a chlorine attached to the right of the metal (along the x axis, at least as defined by the orbital labels above). It would not be able to form π overlap with the dyz orbital. The symmetry isn't right.

Figure OR4.6. A lack of proper symmetry between a t2g orbital and a chlorine p orbital makes π bonding impossible.

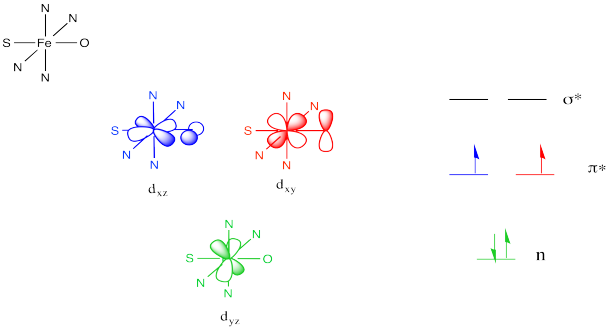

In our example of Cytochrome P450, things are different from the example in which all of the ligands were the same. In Cytochrome P450, only the oxygen and the sulfur can donate. As a result, one of the non bonding d orbitals is not participating in π bonding. That's because the π donors are unable to interact with one of the d orbitals. It is too far away and it has the wrong symmetry to overlap with either of the oxygen p orbitals that can participate in the π bond.

Figure OR4.7. If π-donation is only available along one axis, then only two of the t2g orbitals are raised in energy.

The same would be true for the sulfur atom, since it is located along the same axis as the oxo ligand.

The net result is different from the π donor picture we have seen before. Because the π donation is restricted along one axis, not all of the non bonding d orbitals are elevated to π* levels. Only two of them form this interaction. The third remains unchanged.

Figure OR4.8. Two of the t2g orbitals in the iron oxo complex are antibonding; the other is nonbonding.

The overall frontier picture of an Fe(IV) oxo reveals two unpaired electrons in the π antibonding level. As a result, the pi bond may be considered relatively weak compared to some other metal oxo complexes. That may result in increased reactivity. In contrast, a d0 or d2 oxo is usually much more inert than a d4 oxo because they lack unpaired electrons.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with contributions from other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.