TM1. Transition Metal Complexes

Transition metals are found in the middle of the periodic table. In addition to being found in the metallic state, they also form a range of compounds with different properties. Many of these compounds are ionic or network solids, but there are some molecular compounds, too, in which different atoms are arranged around a metal ion. These compounds are called transition metal complexes or coordination complexes. They are often brightly-coloured compounds and they sometimes play very useful roles as catalysts or even as pharmaceuticals.

Because of their relatively low electronegativity, transition metals are frequently found as positively-charged ions, or cations. These metal ions would not be found by themselves, but would attract other ions or molecules to them. These species bind to the metal ions, forming coordination complexes. The name originates from the term complex ion because the metal ions were composed of different pieces.

- Coordination complexes form when small molecules or ions bind to transition metals.

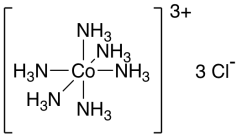

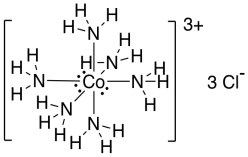

Hexaamminecobalt(III) chloride, [Co(NH3)6]Cl3, is an example of a coordination complex. It is a yellow compound. The "complex" part refers to the fact that the compound has a bunch of different pieces. There is a cationic part, which itself is a moderately complicated structure, plus three chloride anions.

Figure TM1.1. A transition metal coordination complex or complex ion.

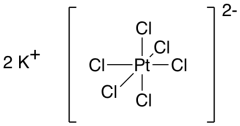

Potassium hexachloroplatinate, K2[PtCl6], is another good example. It is another bright yellow compound. This time, the anion is the more complex part, and there are two potassium ions as well.

Figure TM1.2. Another transition metal coordination complex or complex ion.

- Complex ions formed from form transition metals can be anionic or cationic.

- The overall charge on the complex depends on the balance of charges between the individual pieces of the complex ion.

The formulae for coordination complexes always give you hints about the structures. The stuff inside the square brackets always makes up one of the ions. In that part, there are a number of things attached to the transition metal. Those things attached to the transition metal are called ligands; we'll take a closer look at them, later. The part outside the square brackets tells you what the counterions are; those are there to balance out the charge of the ion inside the square brackets.

Very often, the counterions are individual atomic ions, like chloride anions (Cl-) or potassium cations (K+). So, when you see the K2 within the formula, the potassium atoms are not connected together; they are two separate potassium ions: 2 K+. Likewise, the Cl3 at the end of a formula does not really mean a group of three chlorine atoms clustered together; they are three separate chloride ions, 3 x Cl-.

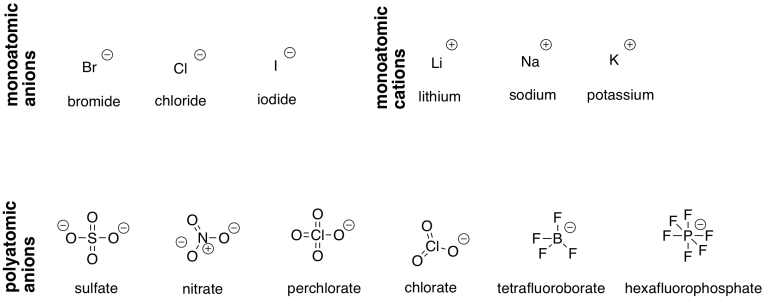

Sometimes, there are polyatomic ions that act as counterions to these complexes. That's especially common in the case of anions. Most often, they are oxoanions, in which an atom has some number of oxygens attached to it. A couple of the most common examples are nitrate (NO3-) and sulfate (SO42-); these ions have been known for hundreds of years. Tetrafluoroborate (BF4-) and hexafluorophosphate (PF6-) are a couple of twentieth-century anions.

A number of common ions are listed in the table below. Most of them have a +1 or -1 charge. Sulfate is the only common example listed with a 2- charge.

Figure TM1.3. Some common counterions for transition metal coordination complexes.

Note that some of these structures use a charge-minimised Lewis structure. In third-row elements, these structures may contain additional bonds to the central atom, going past the octet, in order to lower the number of + and - charges. Sulfate and perchlorate can also be drawn as octet-obedient structures, in which the sulfur and chlorine have true octets, and charge separation occurs. However, hexafluorophosphate has no octet-obedient Lewis structure; any way you draw it, the phosphorus has six bonds.

Problem TM1.1.

Draw the octet-obedient structures for (a) sulfate and (b) perchlorate.

Problem TM1.2.

Indicate the individual ions in the following complexes.

a) [Co(NH3)4Cl2]Cl b) [Co(NH3)5Cl]Cl2 c) [Co(NH3)5NO2]Cl2

d) [Co(NH3)5OH2]Cl3 e) K2[PtCl4] f) Na2[Co(SCN)4]

g) [Pt(NH3)2(OH2)2](NO3)2 h) [Co(NH3)4(OH2)2]2(SO4)3

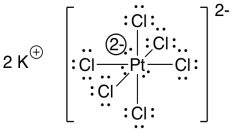

We haven't drawn proper Lewis structures for these coordination complexes so far. You won't usually see full Lewis structures of transition metals compounds, for reasons that you'll see soon, but it's useful to take a look at a couple of examples. For the hexachloroplatinate complex, the Lewis structure is shown below:

Figure TM1.4. The Lewis structure of hexachloroplatinate(VI) ion.

The electron acounting looks like this:

| atom | electrons |

| Pt | 10 e- |

| Cl | 6 x 7 e- |

| charge | add 2 e- |

| total | 54 e- |

Two electrons for each bond takes up 12 electrons. That leaves 42 more. If each chlorine gets three lone pairs, that uses up another 36 electrons. There are six left, and they could be left on the platinum.

That is a lot of electrons. But remember where platinum sits in the periodic table: it's a transition metal. How many electrons does the next noble gas have? Eighteen: that's radon. This structure works out perfectly in terms of reaching a noble gas configuration.

For another example, let's take a look at the cobalt complex.

Figure TM1.4. The Lewis structure of hexaamminecobalt(III) ion.

This time, the electron counting looks like:

| atom | electrons |

| Co | 9 e- |

| N | 6 x 5 e- |

| H | 18 x 1 e- |

| charge | lose 3 e- |

| total | 54 e- |

A dozen of those electrons get used for the six Co-N bonds, leaving 42 more. We need another 36 for the eighteen N-H bonds; that leaves six electrons. We can just put those on the cobalt, like last time.

Each nitrogen ends up with its octet (eight electrons in four bonds). Each hydrogen has its "octet" (two electrons in a bond, corresponding to helium's noble gas configuration. Cobalt also gets its "octet" (eighteen electrons corresponding to krypton's noble gas configuration).

These are still really big, unwieldy numbers. We need a simplification. We won't really count up all of the electrons in coordination complexes because they tend to be assembled from pre-existing parts (the "ligands") that already have their octets. The ligands are just donating their electrons to the metal in the centre. Instead, we focus on that metal, and see how many electrons it has once all of the ligands have been attached.

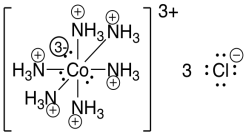

Also, notice that in the Lewis structure of the cobalt complex, we neglected the formal charges. That's actually common practice with transition metal complexes. The reason for that is simply that the structure is getting pretty crowded with all the lone pairs and formal charges. Normally, the lone pairs on the transition metal are not shown, and neither are the formal charges, in order to simplify an already complicated structure.

Figure TM1.4. The Lewis structure of hexaamminecobalt(III) ion with formal charges.

- Coordination complexes are usually drawn without showing formal charges.

- Overall charges on the ions are still drawn.

- Valence electrons are not normally shown on the transition metal.

- These short-cuts are taken to simplify these complicated structures.

On the next page, we will take a look at some common ligands: the pieces that are directly attached to the transition metal ions.

See a more in-depth discussion of coordination complexes in a later course.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted on individual pages. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry

by Chris Schaller is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry

by Chris Schaller is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

Navigation: