MO6a. Assembling the Pieces

So far, we have looked at the ways in which pairs of atomic orbitals could combine to form molecular orbitals -- to form bonds. Just as we think of there being a progression of atomic orbitals from lowest energy to highest (1s, 2s, 2p, 3s...), we can organise these molecular orbitals by order of their energy.

To a great extent, the order of molecular orbitals in energy can be considered to follow from the order of the atomic orbitals from which they are constructed. There are some departures from that rule, sometimes, but that's the simplest place to start. So, in a molecule, the lowest-energy molecular orbitals would be the ones formed from the lowest-energy atomic orbitals, the 1s orbitals.

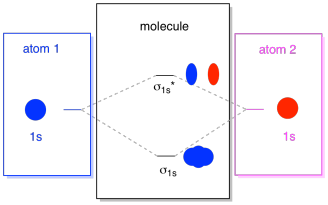

What we see here is a molecular orbital interaction diagram. The middle of the diagram is just the molecular orbital energy diagram. It is analogous to the atomic orbital energy diagram (which goes 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s...). The order of energy so far is σ1s, σ1s*. The sides of the diagram just refer back to where those molecular orbitals came from, with dotted lines to guide you from one place to another. Altogether, the picture says that the 1s orbital on one atom and the 1s orbital on the other atom can combine in two different ways, producing the lower-energy, bonding σ1s and the higher-energy, antibonding σ1s*.

Note that we have not added any electrons to that molecular orbital energy diagram yet, but when we do, we will just fill them in from the bottom up, just like we would an atomic orbital energy diagram.

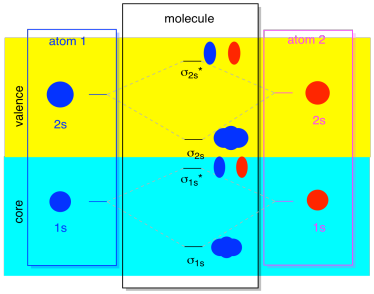

The next lowest set of atomic orbitals is the 2s level. These spherical orbitals would comine very much like 1s orbitals, and we would get a similar diagram, only at a slightly higher energy level.

Most of the time, we aren't going to see both the σ1s and the σ2s displayed in the diagram. That's because if there are any 2s electrons, then those 1s electrons are really core electrons, not valence. They are buried a little deeper in the atom, and they don't play a very important role in bonding. Ignoring the core electrons is pretty common; if you recall, in atomic electron configurations we might write [He]2s22p4 instead of 1s22s22p4 for oxygen; we were ignoring the core. When we drew Lewis structures, we gave oxygen six electrons, rather than eight; we were ignoring the core.

In the context of MO, suppose we do have 2s electrons. That must mean that each atom has two 1s electrons of its own, for a total of four. When those four electrons are filled into the MO diagram from the bottom up, they will occupy both the bonding σ1s and the antibonding σ1s*. The effect of both those combinations being occupied is to cancel out the bonding; those two pairs of electrons remain non-bonding. So we can ignore them and we aren't really missing anything.

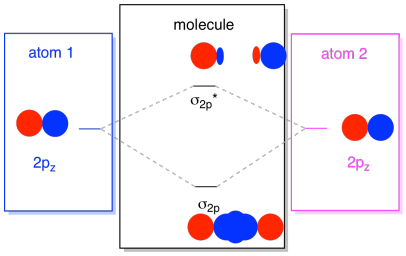

The 2s orbitals aren't the only ones in the second shell. There are also 2p orbitals. Remember, there are a couple of very different ways in which p orbitals can combine with each other, depending upon which axis they lie. If they do not lie parallel to each other -- that is, if they are prependicular to each other, such as a px and a py -- then they cannot interact with each other at all. The pz on one atom could interact with the pz on the other atom, however, because they are parallel to each other.

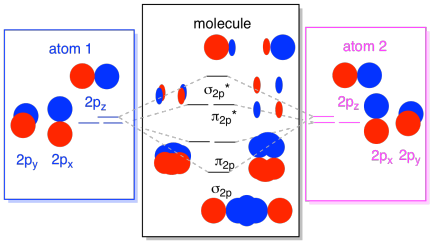

Usually, we define the z axis as lying along the line between the two atoms we are looking at. Two pz orbitals would lie along that axis, each with a lobe extending into the space between the atoms, and each with another lobe extending away, in the other direction.

The resulting combinations are called σ because they do lie along the axis between the atoms (that's exactly what σ means, in terms of bonding). There is a σ combination, if the overlapping lobes are in phase with each other, and σ* combination, if those lobes are out of phase with each other. Because these new orbitals arise from the atomic 2p orbitals, we call them σ2p and σ2p*.

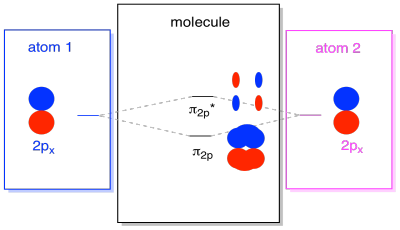

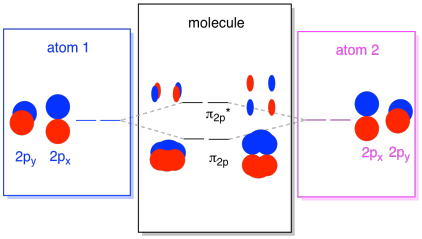

There are also those p orbitals that do not lie along the bond axis, or the axis between the two atoms. The px orbitals are perpendicular to the pz orbitals we just looked at, and therefore perpendicular to the axis between the bonds. However, they are still parallel to each other, and they can still form combinations. These two orbitals would form an in-phase combination and an out-of-phase combination.

Note that the energetic separation between these two combinations is a little smaller that the gap between the σ2p and σ2p* levels. The difference is related to the degree of overlap between the atomic orbitals. The on-axis orbitals project strongly into the same space; they overlap a lot, and they interact strongly. The off-axis orbitals brush against each other, interacting less strongly, and resulting in smaller energetic changes. The gap between the π2p orbital and π2p* orbital is therefore much smaller than the one between the σ2p and σ2p* orbitals.

There are actually two of those off-axis p orbitals. In addition to the px set, we would have a py set. If the px set is in the plane of the screen, the py set has one orbital sticking out in front and one hidden behind. Nevertheless, the combinations between the two py orbitals are exactly the same as what we saw between the two px orbitals. They are just rotated into a perpendicular plane with respect to the px combinations.

We can put all of those 2p-based orbitals together in one diagram. It's starting to get a little more crowded, but this diagram is just a combination of the pieces we have already seen. Note that the px, py, and pz atomic orbitals all start out at the same energy (we have stacked them here so that you can still see the correlation between the atomic and molecular orbitals). That means that the π2p & π2p* orbitals will be "nested" between the σ2p & σ2p* orbitals.

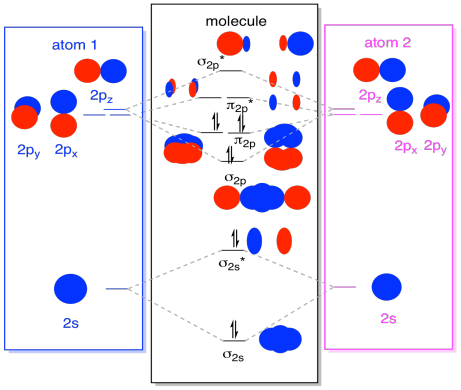

Finally, keeping in mind that the 2p orbitals are higher in energy than the 2s orbitals, we can combine those pictures into one diagram. Again, we have seen these individual pieces before; we are just assemblimg them, now.

While we are at it, we can can add in the electrons. How? It's just the total number of valence electrons. For an example, we have used N2. Each nitrogen has five valence electrons, for a total of ten, so we have just filled in ten electrons, starting at the bottom of the molecular orbital energy level diagram. If this were another molecule, such as F2 or O2, we would construct the overall diagram in a similar way, but just use a different number of electrons.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted on individual pages. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry

by Chris Schaller is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry

by Chris Schaller is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

Navigation: