Electrophilic Addition to Alkenes

EA8. Epoxidation

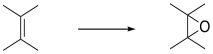

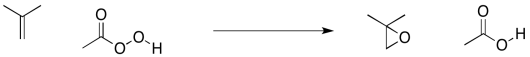

Epoxidation is the addition of a single oxygen atom across a C=C double bond. The resulting compound is an epoxide, also called an oxirane. Oxiranes are reactive ethers that play important roles in synthesis.

Figure EA8.1. Epoxidation of an alkene.

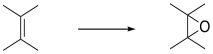

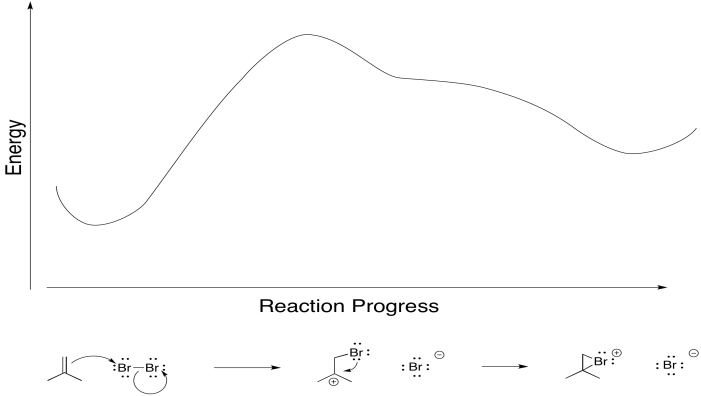

Earlier, we saw that alkenes can donate their pi electrons to electrophiles such as "Br+". In the bromonium ion that results, a lone pair on the bromine can donate back to the incipient carbocation, leading to a more stable intermediate.

Figure EA8.2. The formation of a cyclic bromonium ion from an alkene is a concerted process.

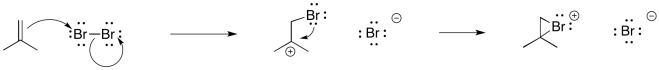

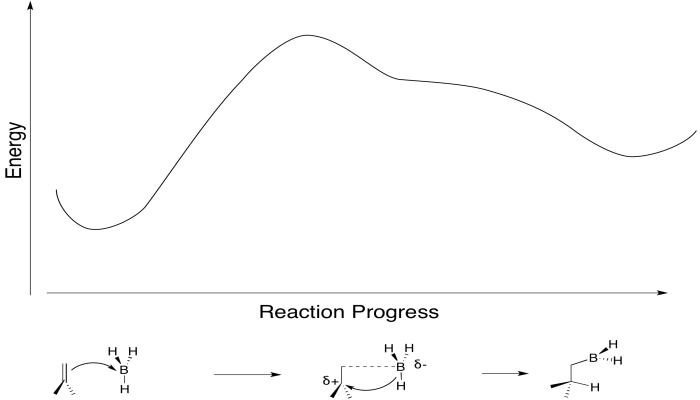

We have also seen that addition to alkenes can sometimes be concerted, happening all at once, rather than one step at a time. For example, in hydroboration, the boron and the hydrogen add to the double bond at the same time.

Figure EA8.3. The formation of an alkylborane from an alkene is a concerted process.

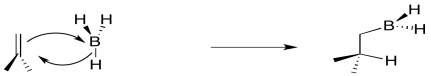

Conceptually, it may be easier to break down alkylborane formation into separate steps. In the first conceptual step, the Lewis acidic or electrophilic boron atom attracts electrons from the nucleophilic alkene, just like a proton. In the second conceptual step, the boron anion donates a hydride to the carbocation. Really, these events do not happen in two separate steps, although some charge separation may occur in the transition state. The boron is adding just slightly ahead of the hydrogen. However, as soon as positive charge starts to build up on carbon, and negative charge starts to build up on boron, the hydride is immediately donated. Time is not allowed for the charged intermediate to fully form before proceeding.

Figure EA8.4. A primary alkene-to-boron donation causes an immediate B-H bond-to-carbon donation.

Really, that's what is happening to the bromine, too. As the alkene starts to donate its pi electrons to the bromine and begins to build up positive charge, the bromine's lone pair is drawn back to the alkene. As a result, the intermediate that we imagine with a full positive charge on carbon and no charge on bromine exists too fleetingly to be considered an intermediate at all. As soon as it begins to form, it is already turning into something else.

Figure EA8.5. A primary alkene-to-bromine donation causes an immediate bromine-to-carbon back-donation.

That sort of concerted addition happens with some other electrophiles, too. If an atom is electrophilic, but also has a lone pair to donate, that cyclic transition state can lead to the product in one step.

Alkene epoxidation is another example of this kind of reaction, although there is a little more going on in this case. An epoxidation is the transfer of an oxygen atom from a peroxy compound to an alkene. Peroxides contain O-O bonds, which are relatively weak and reactive. Most of the time, peroxycarboxylic acids (or sometimes just "peroxyacids" for short) are used as the oxygen donor. Peroxycarboxylic acids are like carboxylic acids that contain an OOH group attached to the carbonyl rather than an OH group.

Figure EA8.6. An epoxidation reaction using a peroxycarboxylic acid.

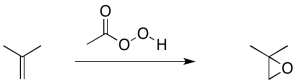

To simplify a little bit, look at the reaction from the point of view of the alkene. It's just picking up an oxygen atom, because the peroxide had an extra one.

Figure EA8.7 An epoxidation reaction, ignoring the by-product.

When the oxygen atom is transferred, it forms an epoxide (again, sometimes called an oxirane). It is a three-membered ring containing two carbons and an oxygen. We don't really need to worry about the carboxylate by-product because it is water-soluble; it can be removed easily with an aqueous workup, leaving the epoxide behind.

Epoxidation results in transfer of an oxygen atom from a peroxide to an alkene.

Peroxides are compounds containing weak O-O bonds.

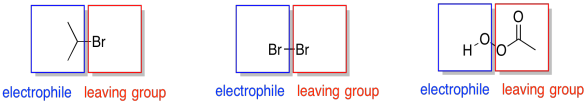

Like in a bromination, the electrophile is deceptive. It is an oxygen atom, which we more naturally think of as a nucleophile. However, just as Br2 contains an atom attached to a good leaving group (Br -), so do the kinds of oxygen compounds used in epoxidation. In a peroxycarboxylic acid, we could imagine the leaving group is a resonance-stabilized carboxylate anion, RCO2-, or even a neutral carboxylic acid, RCO2H.

Figure EA8.8. Like molecular bromine, a peroxycarboxylic acid contains a good leaving group.

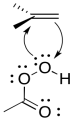

As in the bromination, as soon as the alkene begins donating to the electrophile, a lone pair can donate back, so that an unstable cation does not have to form.

Figure EA8.9. An epoxidation reaction involves both donation from and back-donation to an alkene.

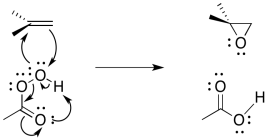

The entire mechanism is believed to be concerted, based on a number of lines of experimental evidence. A number of things need to be accomplished; in addition to the oxygen donation, the leaving group must leave, and a proton must be transferred.

Figure EA8.10. A concerted epoxidation also includes intramolecular proton transfer in the peracid.

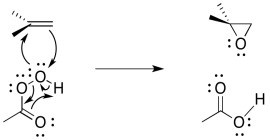

The reaction mechanism can be cleaned up slightly because it is thought to be an example of a pericyclic reaction. Pericyclic reactions frequently involving three pairs of electrons moving in a circle. Like the three pairs of electrons in a benzene ring, this structure is thought to be unusually stable.

Figure EA8.11. A more common way of drawing the epoxidation mechanism.

Apart from peroxy acids, many other peroxides can be involved in epoxidations, as well as some metal oxides. In some cases, the reaction is extremely slow, but works better in the presence of a catalyst.

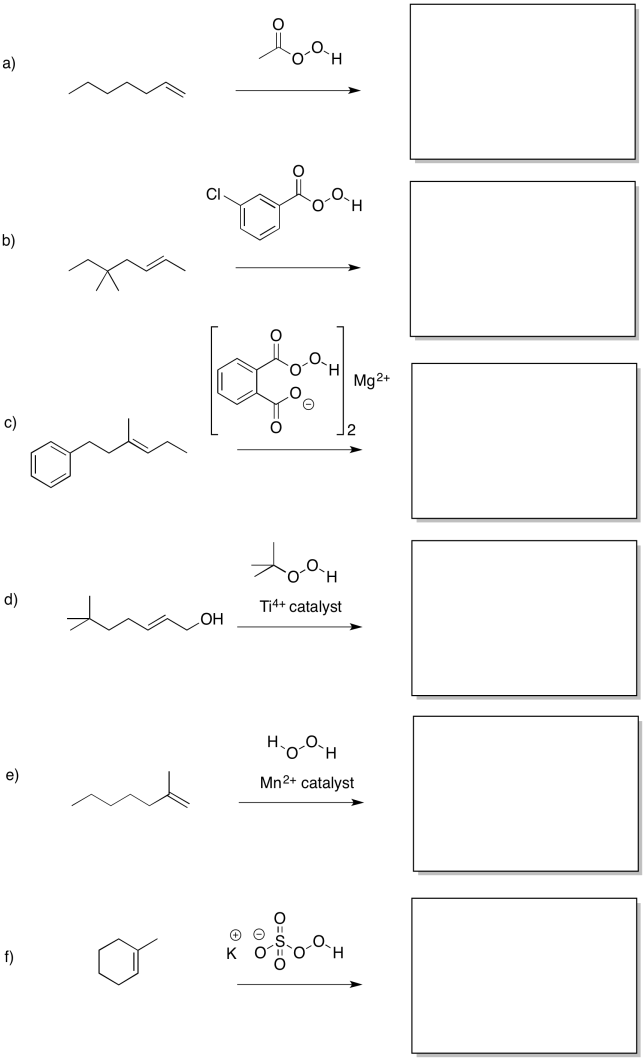

Problem EA8.1.

Predict the products of the following reactions.

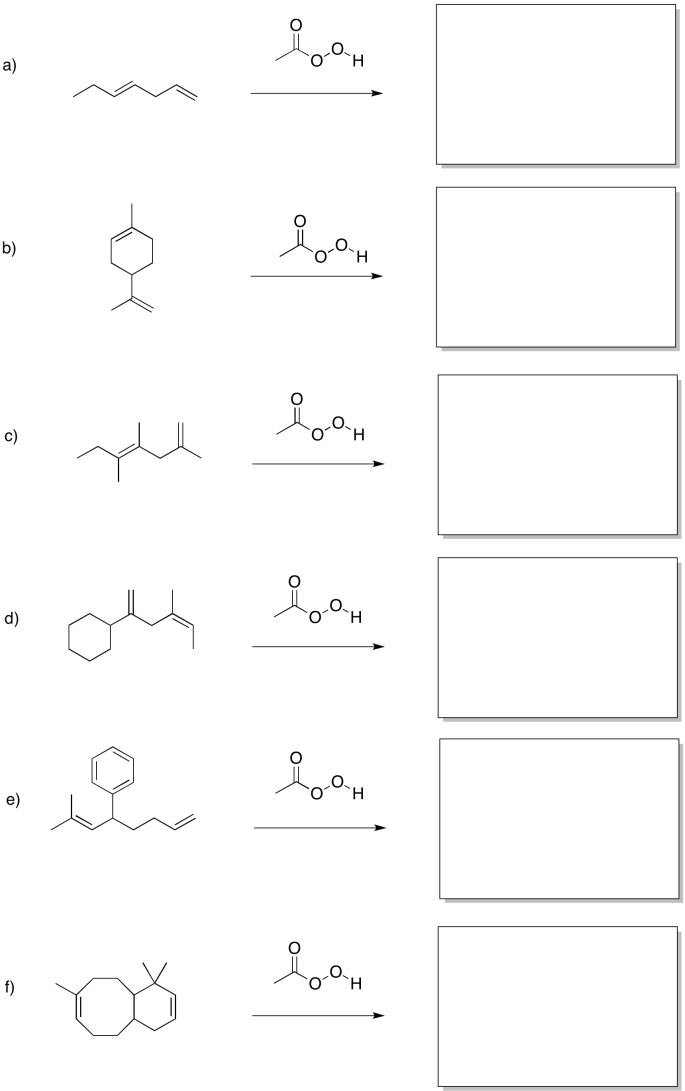

Epoxidation reactions display an almost counter-intuitive selectivity. Unlike hydrogenation reactions, which are generally easier with less-substituted alkenes, epoxidations are much faster with more-substituted alkenes. In the case of hydrogenations, the selectivity can be understood as a combination of steric factors (the alkene must bind to a catalyst) as well as thermodynamicic factors (more substituted alkenes are more stable, so they are less likely to react). However, in epoxidations, the more electron-rich the alkene, the more easily it can be induced to react with the peroxide. More substituted alkenes are generally more electron-rich than those that are substituted only with electron-poor hydrogens.

Figure EA8.12. Order of reactivity of alkenes towards epoxidation.

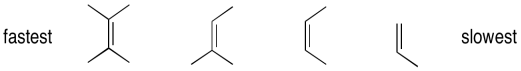

Problem EA8.2.

Predict the products of the following reactions.

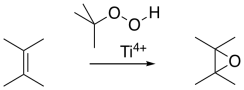

Peroxyacids aren't the only sources of oxygen for epoxidations. Sometimes, simpler peroxides such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide (Me3COOH) can be used. As mentioned before, metal ions can sometimes accelerate epoxidations, and they are often used with these oxidants.

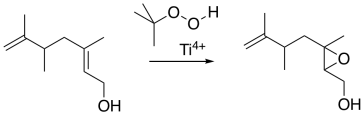

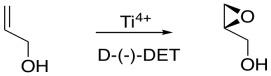

Figure EA8.13. A titanium-catalyzed epoxidation.

The Sharpless epoxidation is one of the most common methods of catalytically adding an oxygen across a double bond. The method generally employs a titanium catalyst; similar approaches use vanadium catalysts or other metallic species. The Sharpless epoxidation is important partly because it selectively epoxidizes allylic alcohols: compounds containing a C=C-C-OH unit. That means that, in addition to being able to selectively epoxidize more-substituted double bonds in the presence of less-substituted double bonds, we can also select double bonds that are close to alcohols.

Figure EA8.14. A Sharpless epoxidation of an allylic alcohol.

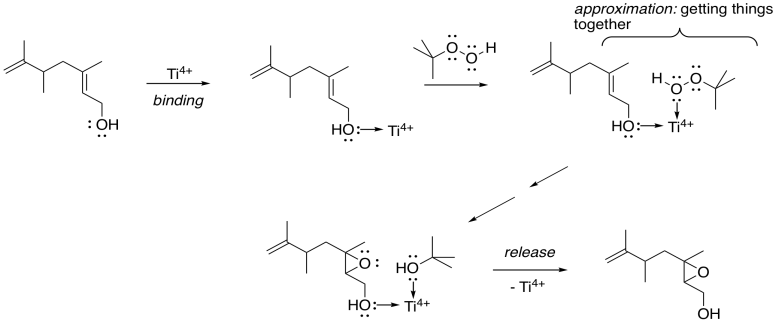

Problem EA8.3.

Circle the allylic alcohol in each of the following compounds.

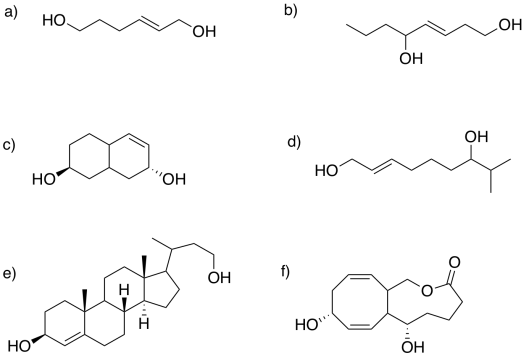

How does the metal catalysis selectively identify that position? Remember, one of the important strategies in enzyme catalysis is approximation: the act of bringing two things together. An alcohol is a potential lone pair donor, so it could become a ligand for a metal ion. Ti4+ and V4+ happen to be very oxophilic -- they bind well to oxygen -- and so they are particularly suited for this task.

Figure EA8.15. Approximation playing a key role in Sharpless epoxidation.

In this scheme, we're not worrying about exactly how the titanium ion gets to peroxide to give up its extra oxygen to the alkene; that's complicated. However, the fact that both the allylic alcohol and the peroxide can bind to the titanium gets them closer together, and makes them more likely to react with each other.

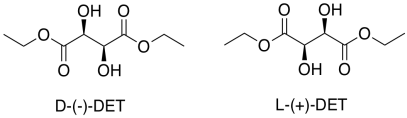

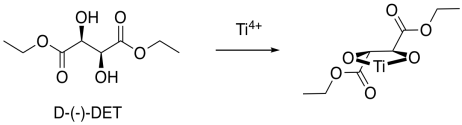

That's only part of the story of the Sharpless epoxidation. The other reason this method is important is its stereoselectivity. To get stereoselectivity, a chiral ligand is added for the titanium. It's usually diethyl tartrate (DET) or diisopropyl tartrate (DIT). Tartrate is chiral; there is a D-(-)-enantiomer and a L-(+)-enantiomer. The D and L are common symbols used to designate enantiomers in sugars; they relate the structure back to the biochemical grandparents of all sugars, D-glyceraldehyde and L-glyceraldehyde. The (-) and (+) symbols refer to the characteristics of this particular compound in polarimetry; the (+) enantiomer rotates plane polarized light in a clockwise direction, whereas the (-) enantiomer rotates plane polarized light in a counter-clockwise direction.

Figure EA8.16. A chiral tartrate ligand used in Sharpless epoxidation.

Problem EA8.4.

Assign stereochemical configurations (R and S) to the tartrates to confirm that they are enantiomers of each other.

If the D-(-)-isomer is added, one possible enantiomer of the product is obtained. If the L-(+)-isomer is added, the other possible enantiomer is obtained.

Figure EA8.17. Sharpless epoxidation to make a chiral epoxide.

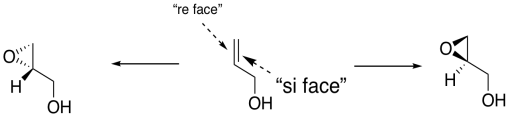

In general, we would get one enantiomer if the oxygen were added to one face of the alkene and the other enantiomer if the oxygen were added to the other face. In the drawing below, the face of the alkene towards us is sometimes called the "re face" (pronounced, ray face). The face of the alkene away from us is called the "si face" (see face). These words sound related to R and S configuration, and they sort of are like that, but they are used to describe two different faces of a flat molecule. Adding oxygen to the re face gives on enantiomer; addign oxygen to the si face gives another.

Figure EA8.18. An oxygen atom could be added to either the front face or the back face of a prochiral alcohol, giving different enantiomers.

How does this preferred reactivity work? How does the metal manage to add the oxygen to one face but not to the other? Tartrates are oxygen-rich and so they bind very well to titanium. Remember, if we have a reaction site and we make it chiral, one enantiomer of the product is generally preferred. Enzymes are very compicated, chiral molecules, and they are good at producing one enantiomer of a product. By comparison, the titanium DET complex is a relatively simple chiral molecule, but it uses the same idea.

Figure EA8.19. An asymmetric shape is formed when tartrate binds the titanium ion.

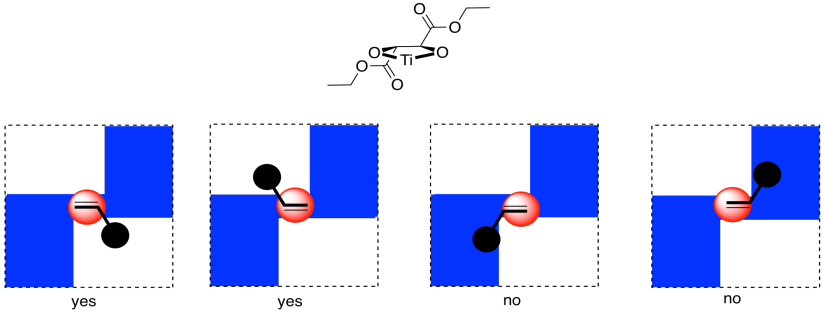

Now, it is really very difficult to look at these conditions and predict exactly which enantiomer would be formed in a reaction. However, we can look at a factor that might illustrate an underlying reason for the preference. In quadrant analysis, we look at the general shape formed by that bidentate tartrate ligand on the metal. In the pictures below, the red ball is the metal atom. The tartrate ligand extends up and to the right as it sits on the metal, and also down and to the left; it is cartooned in blue. As a result, if we think of the metal as sitting in the middle of a square, alternating corners of that square are filled, and the other corners are empty.

Figure EA8.20. "Quadrant analysis" with titanium tartrate: one face of the alkene binds preferentially, whereas the other face is blocked.

Imagine the alkene approaching that metal. The alkene will probably have a preferred orientation in which it will bind. Just for example, maybe it needs to bind with the double bond in the same plane as the ring formed by the titanium and the oxygens (horizontally in the picture). If it does that, it can reduce steric interactions with the ligand by binding one face of the alkene preferentially to the metal, keeping the biggest substituent on the alkane (the black ball) in a relatively open space. The alkene could also bind if rotated upside down compared to the first picture, but the same face would still be towards the titanium.

On the other hand, if the alkene tries to bind through the other face of the pi bond, the largest substituent would be in a more crowded space. That might be less favourable.

Overall, if the alkene has a preferred face that it will bind to the metal, then anything delivered from that metal will land on that face, and not the opposite one.

There are lots of variations on this model. Maybe it isn't steric interactions that influence how the alkene approaches the metal. Maybe it is some other factor, like hydrogen bonding, that pulls in the alkene oriented in one direction and not another. Nevertheless, although the details of a particular case make the outcome very difficult to predict, the general idea is a familiar one: a chiral molecule will fit preferentially one way with another molecule, because of its asymmetric shape.

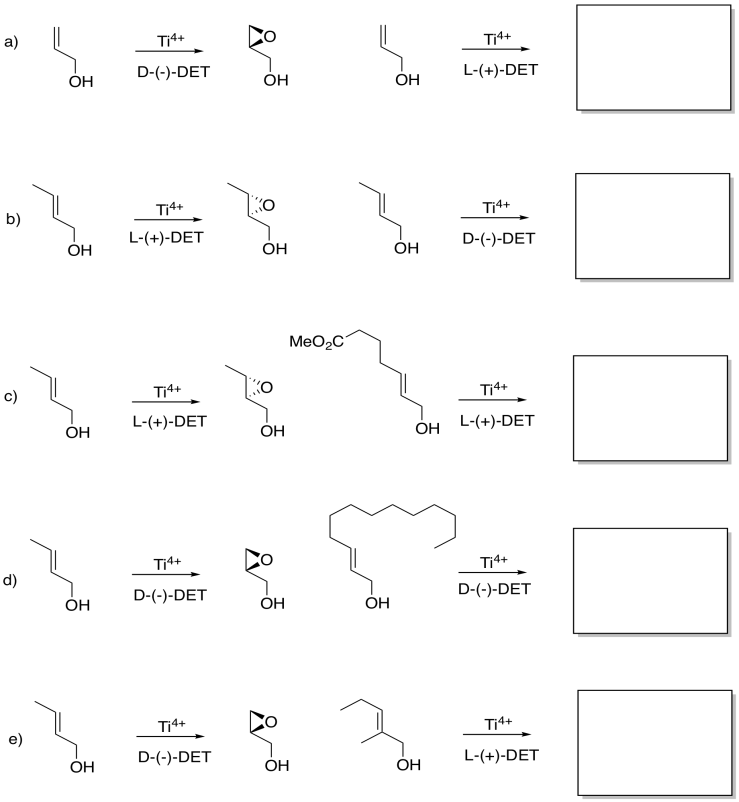

Problem EA8.5.

Although you may not be able to predict off the top of your head which enantiomer is formed in a Sharpless epoxidation, given one result, you may be able to guess another. Given the reaction on the left, see what you can tell about the reaction on the right.

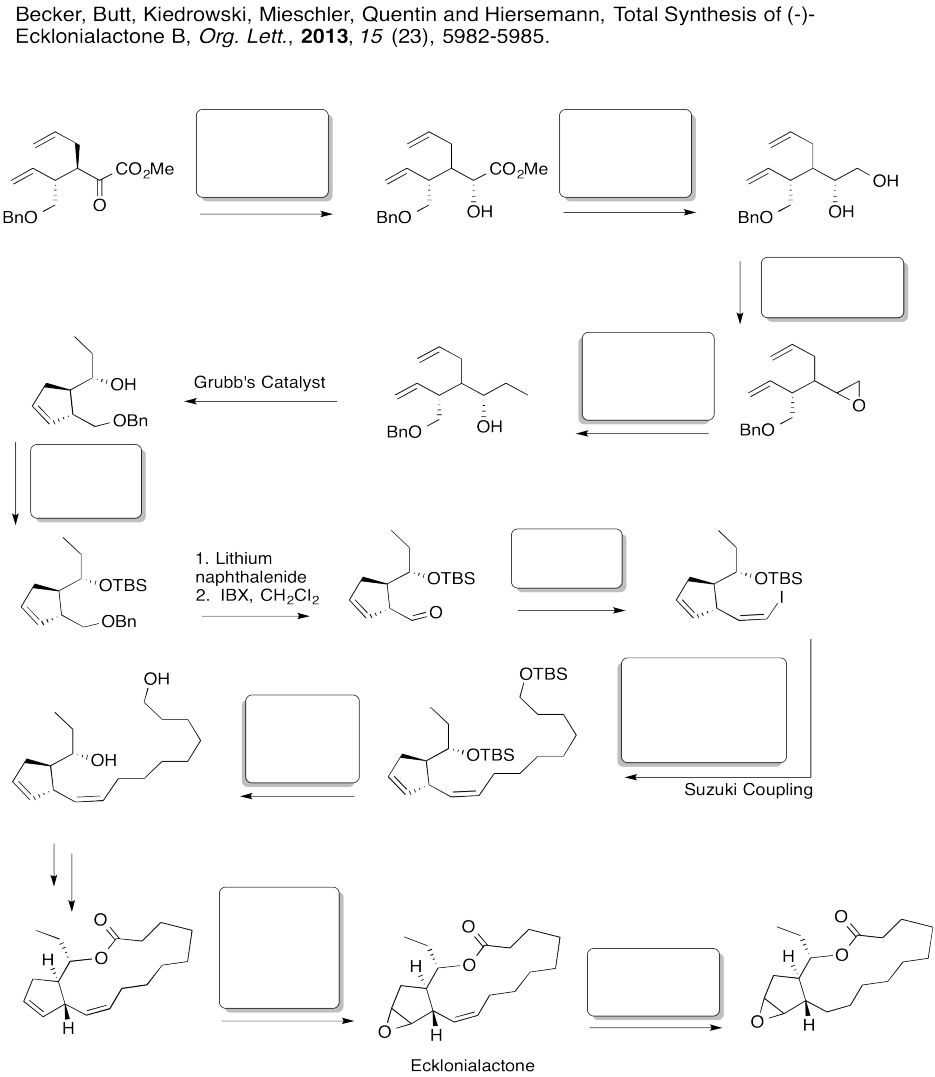

Problem EA8.6.

Fill in the boxes in the following synthesis.

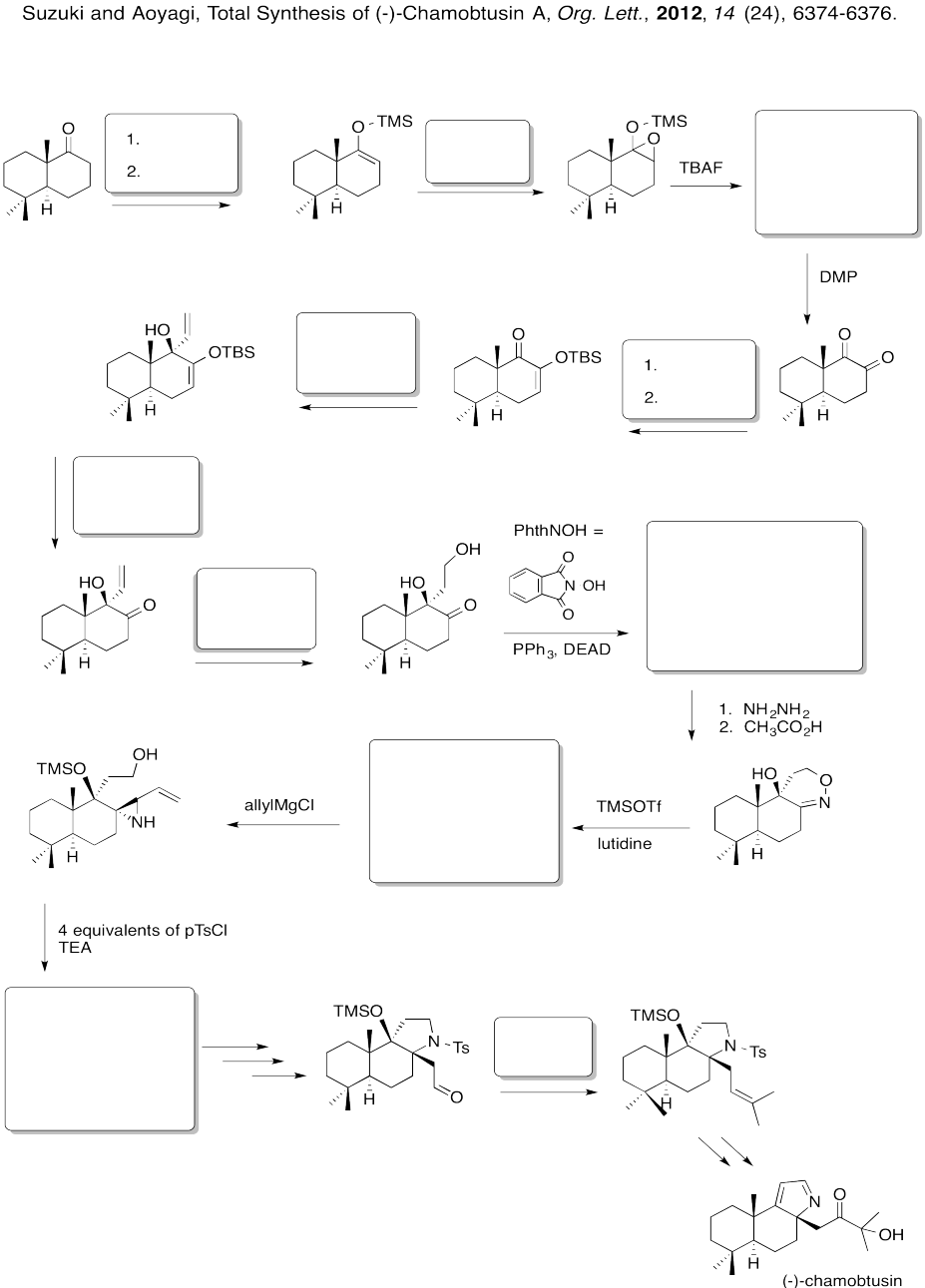

Problem EA8.7.

Fill in the boxes in the following synthesis.

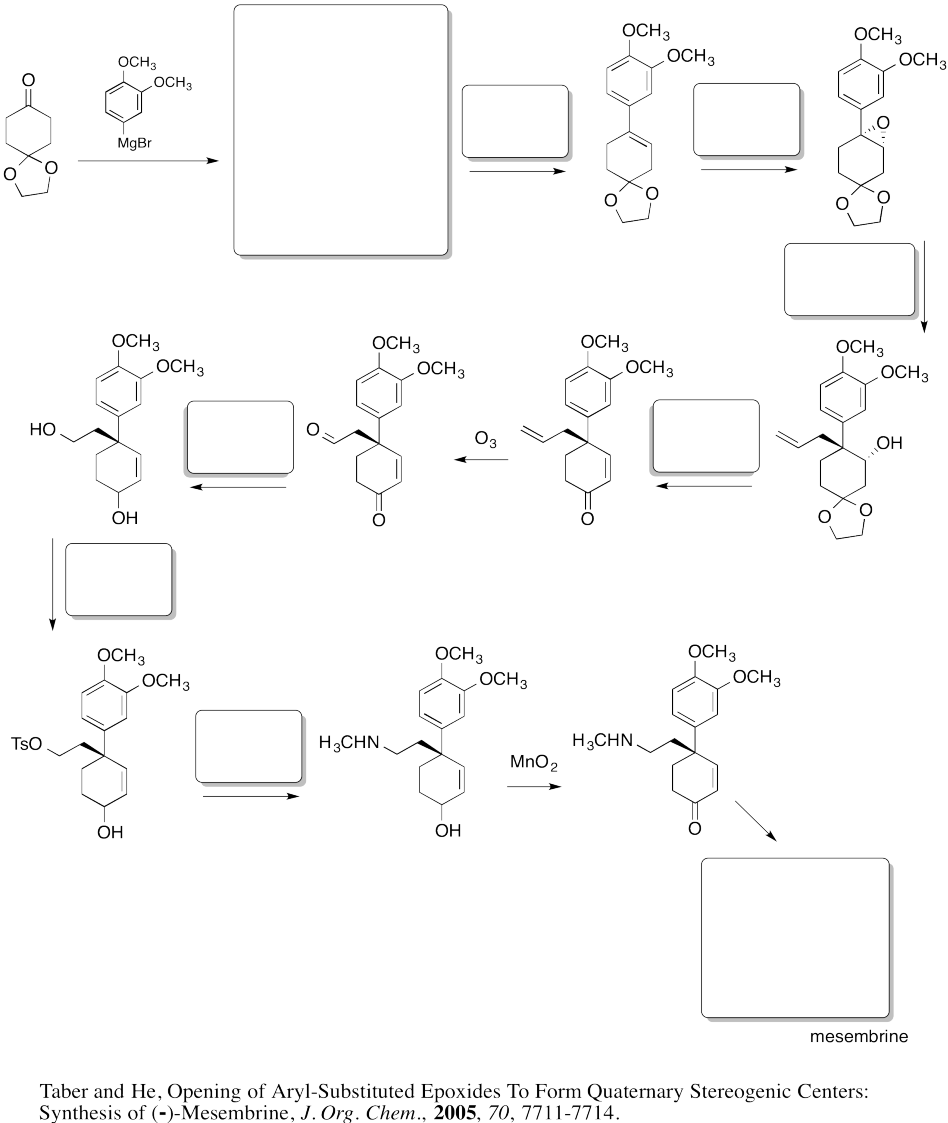

Problem EA8.8.

Fill in the boxes in the following synthesis.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: