Reactivity in Chemistry

Nitrogen Reduction

NF4. Model Studies for Nitrogen Binding

If nitrogen is to be reduced, it first has to be bound. However, nitrogen is remarkably inert. Chemists routinely run reactions under an atmosphere of pure nitrogen because of its lack of reactivity. Fine chemical companies bottle compounds under nitrogen to ensure that the contents remain in pristine condition while sitting on the shelf. If nitrogen doesn't react with anything, how does it react with an iron atom in nitrogenase?

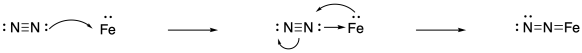

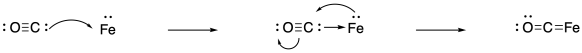

What is the weakness of the dinitrogen molecule? That turns out to be related to its strength. The enormously strong nitrogen-nitrogen triple bond is composed of a sigma bond and two pi bonds. The corresponding antibonding orbital allows nitrogen to act as a weak pi acceptor.

That means there is a chance of getting the very unreactive nitrogen molecule to bind to a transition metal. An occupied d orbital on an iron atom could back-donate into that nitrogen orbital, holding the dinitrogen more securely on the iron. The nitrogen can then be bound.

Figure NF4.1. Bonding and backbonding between iron and nitrogen.

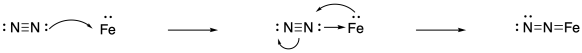

Just to make that scenario more likely, the metal could be tuned in order to maximise its ability to backbond with the nitrogen. That means it needs a lot of electron density. An electron-rich metal atom would readily donate electron density into nitrogen's pi acceptor orbital. Then the nitrogen would bind more tightly.

One factor that would help is a low oxidation state. A low oxidation state on the metal would leave it with more electron density to donate to the nitrogen pi acceptor orbital.

A secondary factor is strongly donating ancillary ligands. These other ligands would play a supporting role by lending additional electron density to the transition metal so that it could bind to the nitrogen even more tightly.

Figure NF4.2. The role of ancillary ligands in backbonding from iron to nitrogen.

As with other metalloproteins, researchers have spent a great deal of effort studying nitrogenase. They have also expended a tremendous amount of effort studying model compounds. Model compounds are simpler molecules that incorporate selected aspects of the metalloprotein. By intentionally designing a model compound to include certain features of the metal centre in the protein, researchers can evaluate what role those features play in the reactivity of the metalloprotein.

It's pretty obvious that we might want a model compound for nitrogenase to contain iron atoms. After all, nitrogenase contains a number of iron atoms at its active site. Of course, it also contains molybdenum, or in some cases vanadium. A model compound might contain those atoms, instead. Alternatively, it could contain atoms other than the ones found in the native enzyme. That would be a sort of pushing-the-envelope approach. If an electron-rich metal is important, how electron rich can we go? Or how electron-poor can we get and still be able to bind nitrogen? By exploring things that aren't part of the natural system, we might better see the importance of those things that are.

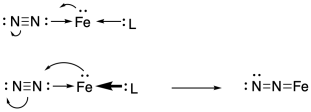

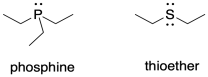

The same is true with the ancillary ligands, those that support the metal but that may not be directly involved in catalysis. The electron-rich sulfides in nitrogenase may be an important part of a model compound. So could phosphines, whose phosphorus donor atoms are of a similar size to sulfur. Phosphines are commonly used industrially in organometallic catalysis and might make good mimics of the sulfur ligands in nitrogenase.

Problem NF4.1.

Consider the ligand type presented by a phosphine compared to a thioether. What might be the disadvantage of using a phosphine as a stand-in for a sulfur donor?

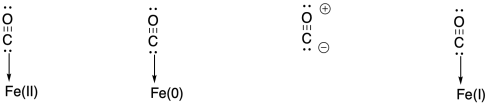

Having said all of that, it is worth emphasizing that binding nitrogen is still not easy. Sometimes, researchers who want to study the potential for nitrogen binding in a given complex start with binding carbon monoxide instead. Why carbon monoxide? First of all, it is much easier to bind than dinitrogen. It is a much stronger pi acceptor, because the pi antibonding orbital is much more heavily located on the carbon that sigma donates to the metal. Of course, you may already know that there are some important transition metal reactions that involve binding and reducing carbon monoxide.

Figure NF4.3. Bonding and backbonding between iron and carbon monoxide.

Furthermore, carbon monoxide studies can be useful because carbon monoxide acts as a "reporter ligand". It is easily monitored by IR spectroscopy, for instance. Dinitrogen is a poor candidate for IR study because of the non-polar N-N bond. (It can be observed via Raman spectroscopy, which gives similar information but is slightly more complicated to run.) The CO bond is easily detected in the IR spectrum, it is in a region that isn't usually cluttered with other peaks from other bonds, and it is quite sensitive to the oxidation state of the metal. That's because of the strong back-bonding from a filled metal d orbital into the pi antibonding orbital of carbon monoxide. The more back-donation from the metal, the weaker the CO bond, resulting in a drop in the frequency in the IR spectrum.

Problem NF4.2.

Rank the following species in terms of their CO stretching frequency in the IR spectrum.

Problem NF4.3.

Nitrogen can bind to metals in a number of ways. Draw structures that illustrate the following binding modes:

a) an end-bound, terminal nitrogen ligand bound via a lone pair

b) a side-bound, terminal nitrogen ligand bound via donation from a pi bond

c) an end-bound, bridging nitrogen ligand bound via a lone pair

d) a side-bound, bridging nitrogen ligand bound via donation from a pi bond

e) a bridging nitrogen ligand bound via donation from a pi bond and a lone pair

Problem NF4.4.

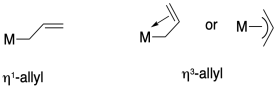

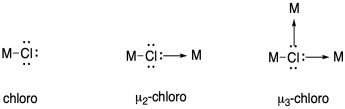

In naming coordination compounds, the prefixes eta (η) and mu (μ) are sometimes used to indicate ligand binding modes such as the ones described above.

Eta describes the number of ligand atoms bound to a single metal atom, and is generally used when there are pi bonds that could donate, bringing two or more donor atoms close to the metal.

Mu is used to indicate a bridging ligand, and if followed by a number it can describe the number of metal atoms bridged by one ligand.

Use these notations to describe the nitrogen binding modes in the previous question.

Problem NF4.5.

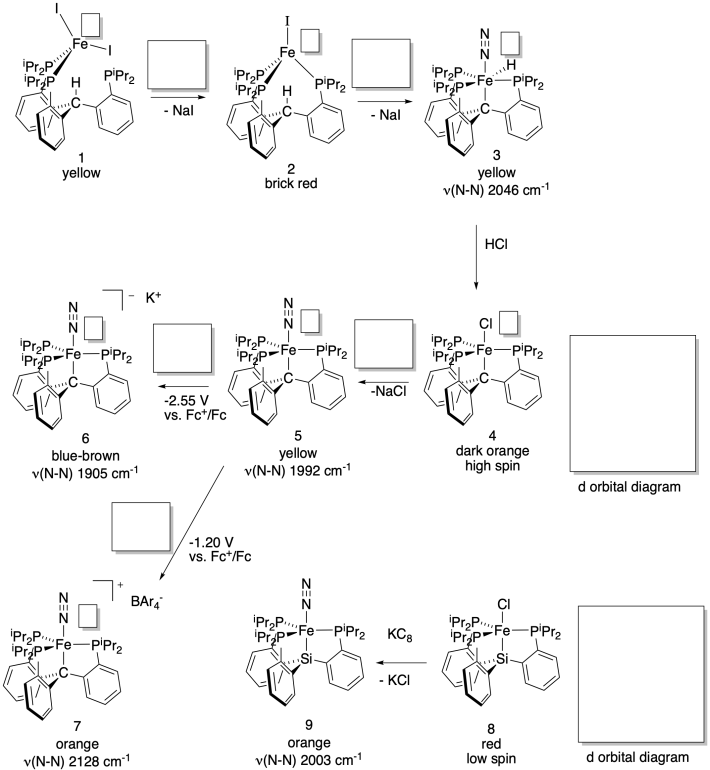

Jonas Peters' lab (Caltech) has developed a new system in an attempt to model the effect of a reported carbon atom in the structure of Fe/Mo cofactor of nitrogenase (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1105-1115). The system catalytically produces ammonia in the presence of N2, acid and sodium metal, Na.

a) Fill in the oxidation states.

b) Fill in missing reagents.

c) Fill in d orbital splitting diagrams.

d)

Explain the differences in the N-N stretching frequencies.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with contributions from other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Navigation: