Reactivity in Chemistry

Photochemical Reactions

PC1. Absorbance

Let's think first about the interaction of light with matter.

We have all seen light shine on different objects. Some objects are shiny and some are matte or dull. Some objects are different colours. Light interacts with these objects in different ways. Sometimes, light goes straight through an object, such as a window or a piece of glass.

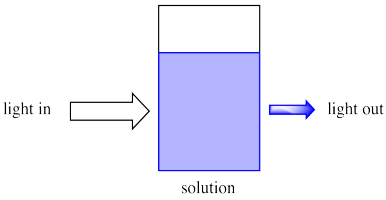

Because chemical reactions are frequently conducted in solution, we will think about light entering a solution.

Imagine sunlight shining through a glass of soda. Maybe it is orange or grape soda; it is definitely coloured. We can see that as sunlight shines through the glass, coloured light comes out the other side. Also, less light comes out than goes in.

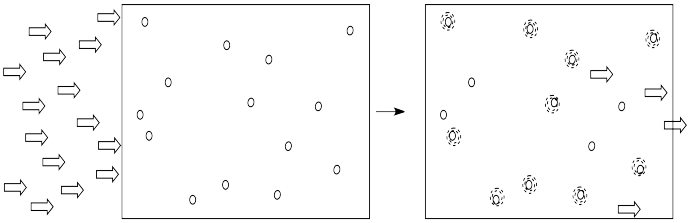

Figure PC1.1. Absorption of light by a coloured solution.

Maybe some of the light just bounces off the glass, but some of it is definitely absorbed by the soda. So, what is the soda made of? Molecules. Some of these molecules are principally responsible for the colour of the soda. There are others, such as the ones responsible for the flavour or the fizziness of the drink, as well as plain old water molecules. The soda is a solution; it has lots of molecules (the solute) dissolved in a solvent (the water).

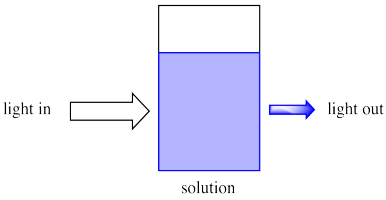

Light is composed of photons. As photons shine through the solution, some of the molecules catch the photons. They absorb the light. Generally, something in the molecule changes as a result. The molecule absorbs energy from the photon and is left in an excited state.

Figure PC1.2. Molecules absorb photons as light passes through a coloured solution.

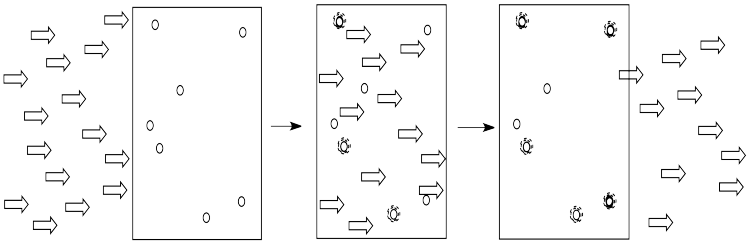

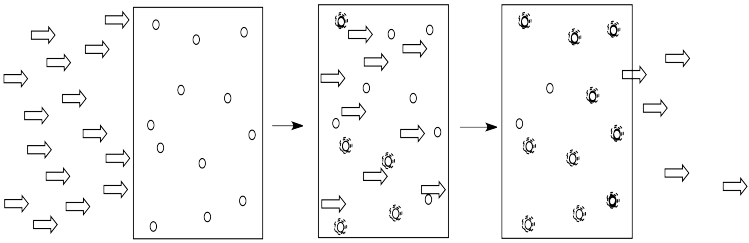

The more of these molecules there are in the solution, the more photons will be absorbed. If there are twice as many molecules in the path of the light, twice as many photons will be absorbed. If we double the concentration, we double the absorbance.

Figure PC1.3. More molecules absorb more light.

Alternatively, if we kept the concentration of molecules the same, but doubled the length of the vessel through which the light traveled, it would have the same effect as doubling the concentration. Twice as much light would be absorbed.

Figure PC1.4. More photons are absorbed if the path through the solution gets longer.

These two factors together make up part of a mathematical relationship, called Beer's Law, describing the absorption of light by a material:

A = ε c l

in which A = Absorbance, the percent of light absorbed; c = the concentration; l = the length of the light's path through the solution; ε = the "absorptivity" or "extinction coefficient" of the material, which is a measure of how easily it absorbs a photon that it encounters.

That last factor, ε, suggests that not all photons are absorbed easily, or that not all materials are able to absorb photons equally well. There are a couple of reasons for these differences.

Problem PC1.1.

Calculate the absorbance in the following cases.

a) A sample with a molar absorptivity ε = 60 L mol-1cm-1 is diluted to a 0.01 mol L-1 solution in water and placed in a 1 cm cell.

b) A sample with a molar absorptivity ε = 3,000 L mol-1cm-1 is diluted to a 3.5 x 10-5 mol L-1 solution in water and placed in a 1 cm cell.

c) A sample with a molar absorptivity ε = 1.4 L mol-1cm-1 is diluted to a 0.25 mol L-1 solution in water and placed in a 0.5 cm cell.

d) A sample with a molar absorptivity ε = 23,000 L mol-1cm-1 is diluted to a 2.5 x 10-6 mol L-1 solution in water and placed in a 1 cm cell.

e) A sample with a molar absorptivity ε = 14,000 L mol-1cm-1 is diluted to a 0.015 mmol L-1 solution in water and placed in a 1 cm cell.

Problem PC1.2.

Calculate the extinction coefficient in the following cases.

a) 30% absorbance is observed with a 0.01 mol L-1 solution in a 1 cm cell.

b) 25% absorbance is observed with a 0.025 mol L-1 solution in a 1 cm cell.

c) 95% absorbance is observed with a 0.00175 mol L-1 solution in a 0.5 cm cell.

d) 66% absorbance is observed with a 0.025 mmol L-1 solution in a 1 cm cell.

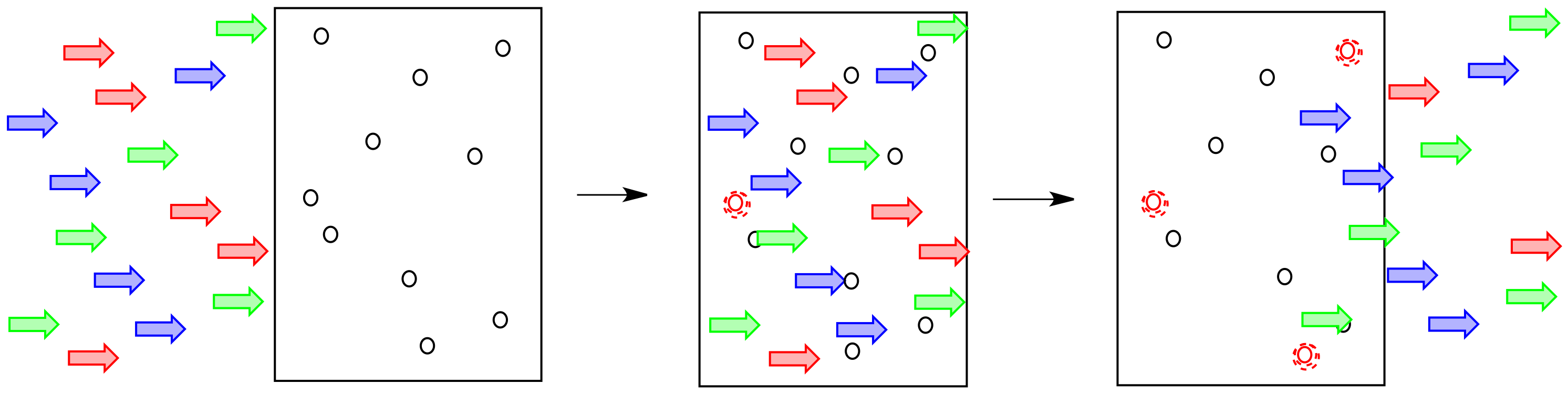

Often a particular soda will absorb light of a particular colour. That means, only certain photons corresponding to a particular colour of light are absorbed by that particular soda.

Figure PC1.5. Specific wavelengths of photons are absorbed by a coloured solution.

How does that affect what we see? If the red light is being absorbed by the material, it isn't coming back out again. The blue and yellow light still are, though. That means the light coming out is less red, and more yellowy-blue. We see green light emerging from the glass.

A "colour wheel" or "colour star" can help us keep track of the idea of complementary colours. When a colour is absorbed on one side of the star, we see mostly the colour on the opposite side of the star.

Figure PC1.6. A colour star shows complementary colours.

Problem PC1.3.

a) What colour of photon is probably most strongly absorbed by a glass of orange soda?

b) What colour of photon is most strongly absorbed by a glass of lime soda?

c) What colour of photon is most strongly absorbed by a glass of blue raspberry kool-aid?

d) What colour of photon is most strongly absorbed by a glass of pineapple soda?

e) What colour of photon is most strongly absorbed by a glass of cherry soda?

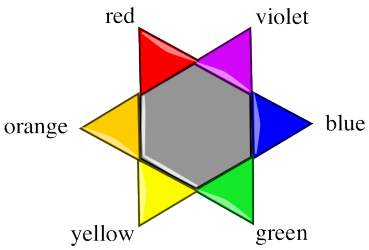

Why do certain materials absorb only certain colours of light? That has to do with the properties of photons. Photons have particle-wave duality, just like electrons. They have wave properties, including a wavelength.

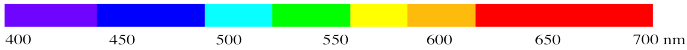

Figure PC1.7. The colour of light depends on the wavelength of the photon.

That wavelength corresponds to the energy of a photon, according to the Planck-Einstein equation:

E = h c / λ

in which E = energy of the photon, h = Planck's constant (6.625 x 10-34 J s-1), c = speed of light (3.0 x 108 m s-1), λ = wavelength of light in m.

Alternatively, the Planck-Einstein equation can be thought of in terms of frequency of the photon: as a photon passes through an object, how frequently does one of its "crests" or "troughs" encounter the object? How frequently does one full wavelength of the photon pass an object? That parameter is inversely proportional to the wavelength. The equation becomes:

E = h ν

in which ν = the frequency of the photon, in s-1.

Problem PC1.4.

a) Calculate the energy of a photon with a wavelength of 1 x 10-5 m.

b) Calculate the energy of a photon with a wavelength of 125 nm.

c) Calculate the energy of a photon with a wavelength of 1025 nm.

d) Calculate the energy of a photon with a wavelength of 450 µm.

e) Calculate the energy of a photon with a wavelength of 850 Å.

Problem PC1.5.

a) Calculate the wavelength of a 1.36 x 10-17 J photon.

b) Calculate the wavelength of a 4.72 x 10-24 J photon.

c) Calculate the wavelength of a 9.26 x 10-7 J photon.

Problem PC1.6.

a) Calculate the wavelength of a photon with a frequency of 6.7 x 1010 s-1.

b) Calculate the wavelength of a photon with a frequency of 1500 MHz.

c) Calculate the frequency of a photon with a wavelength of 9.8 x 10-10 m.

d) Calculate the frequency of a photon with a wavelength of 4.3 x 10-12 m.

The visible spectrum, shown below, contains a very limited range of photon wavelengths, between about 400 and 700 nm. It's a little broader than that, but these are round numbers that are easy to remember.

Figure PC1.8. The spectrum of visible light.

The higher the frequency, the higher the energy of the photon. The longer the wavelength, the lower the energy of the photon.

As a result of this relationship, different photons have different amounts of energy, because different photons have different wavelengths.

Problem PC1.7.

Different portions of the electromagnetic spectrum interact with matter in different ways. Because of that, we can use different wavelengths of light to gain different kinds of information about a material. Calculate the amount of energy involved in the following kinds of interactions, in units of kJ/mol.

a) Molecular bond rotations, measured by microwave spectroscopy. Suppose the microwave has a wavelength 1 mm long.

b) Bond stretching and bending, measured by infrared spectroscopy. Suppose the IR wavelength is 1,000 nm long.

c) Nuclear magnetic moments, measured by radio waves in NMR. Assume the radio wave is 1 m long.

d) The excitation of an electron from one energy level to another, measured by ultraviolet and visible spectroscopy. Assume the visible light's wavelength is 500 nm long.

Problem PC1.8.

The visible spectrum ranges from photons having wavelengths from about 400 nm to 700 nm. The former is the wavelength of violet light and the latter is the wavelength of red light. Which one has higher energy: a photon of blue light or a photon of red light?

Problem PC1.9.

Ultraviolet light -- invisible to humans and with wavelengths beyond that of violet light -- is associated with damage to skin; these are the cancer-causing rays from the sun. Explain their danger in terms of their relative energy.

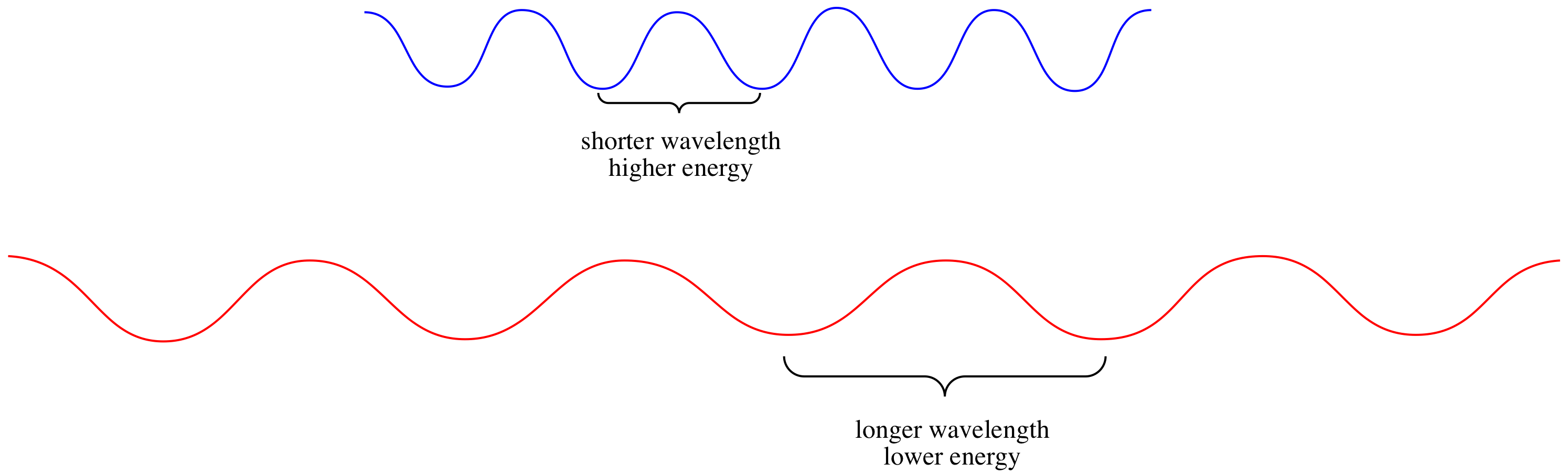

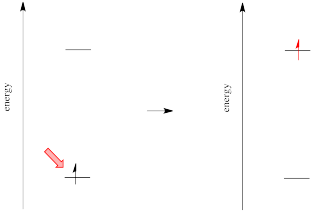

Different materials absorb photons of different wavelengths because absorption of a photon is an absorption of energy. Something must be done with that energy. In the case of ultraviolet and visible light, the energy is of the right general magnitude to excite an electron to a higher energy level.

Figure PC1.9. Absorption of light excites an electron.

However, we know that energy is quantized. That means photons will be absorbed only if they have exactly the right amount of energy to promote an electron from its starting energy level to a higher one (producing an "excited state"). Just like Goldilocks, a photon with too much energy won't do the trick. Neither will a photon with too little. It has to be just right.

Figure PC1.10. The energy of a photon must match an energy difference between orbital levels.

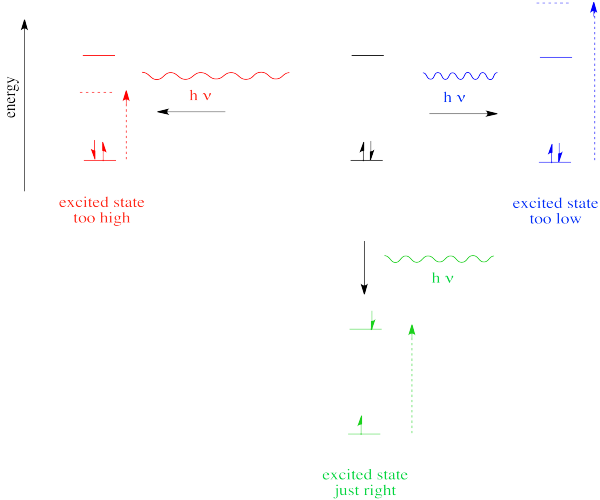

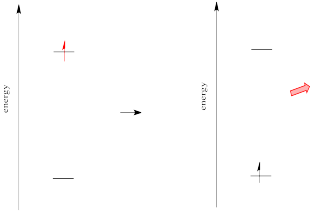

If the absorption of a UV-visible photon is coupled to the excitation of an electron, what happens when the electron falls back down to the ground state? You might expect a photon to be released.

This phenomenon was observed during the late nineteenth century, when scientists studied the "emission spectra" of metal ions. In these studies, the metal ions would be heated in a flame, producing characteristic colours. In that event, the electron would be thermally promoted to a higher energy level, and when it relaxed, a photon would be emitted corresponding to the energy of relaxation.

Figure PC1.11. Relaxation of an electron leads to loss of energy in the form of a photon.

By passing this light through a prism or grating, scientists could separate the observed colour into separate lines of different wavelengths. This evidence led directly to the idea of Niels Bohr and others that atoms had electrons in different energy levels, which is part of our view of electronic structure today.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with contributions from other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: