Reactivity in Chemistry

Radical Reactions

RR10. Living Radical Polymerization

Chain polymerization reactions result in the efficient conversion of monomers into high molecular weight polymers. However, chain termination events result in a broadening of the polydispersity index of the material. In other words, instead of producing a material composed of molecules that are all about the same molecular weight, a wide range of sizes of molecules result. Some of the chains are very short and others are very long. That's a problem, because the chain length (and the associated property, molecular weight) strongly influence the properties of the material. If the size of the molecules is not controlled, neither are the properties. If the properties are not controlled, the material won't perform reliably in its intended application.

Problem RR10.1.

The degree of polymerization of a polymer is simply the average number of monomers incorporated in each polymer chain. Given the following "feed ratios" (ratios of monomer to initiator), what is the expected degree of polymerization in each case?

a) methyl methacrylate : AIBN 500 : 1

b) styrene : benzoyl peroxide 1000 : 1

c) acrylonitrile : tert-butyl peroxide 600 : 3

Problem RR10.2.

The measured degree of polymerization indicates the number average molecular weight of the polymer (Mn). Calculate Mn in each of the following cases.

a) polystyrene, with DP = 1250

b) polymethacrylamide, with DP = 725

c) poly(methyl acrylate), with DP = 1420

Problem RR10.3.

Alternatively, if the number average molecular weight of the polymer is measured, that result can be used to establish the degree of polymerization. What is DP in each of the following cases?

a) polyacrylonitrile, with Mn = 11,450 D

b) poly(vinyl acetate), with Mn = 24,760 D

c) polystyrene, with Mn = 927,000 D

Living polymerization refers to processes in which unexpected chain termination does not occur. The chain keeps growing and growing as long as more monomer is supplied. In extremely hardy cases, the term "immortal" polymerization is sometimes used.

Typically, strategies for living polymerization involve controlling the reactivity of the intermediates. Frequently, the concentration of the growing chains is kept low. If the concentration of growing chains is kept low, then unexpected side reactions involving the reactive growing chain will be kept to a minimum.

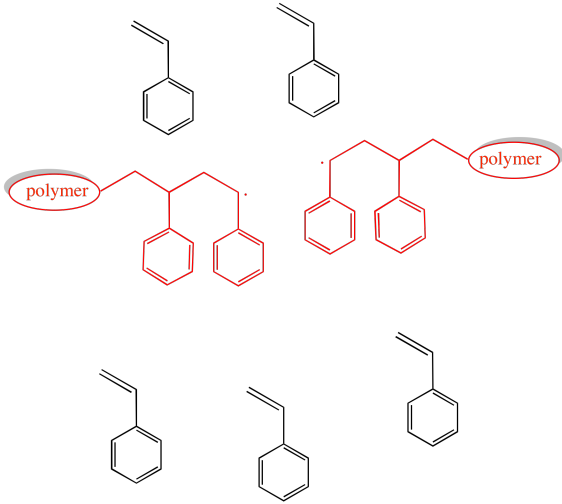

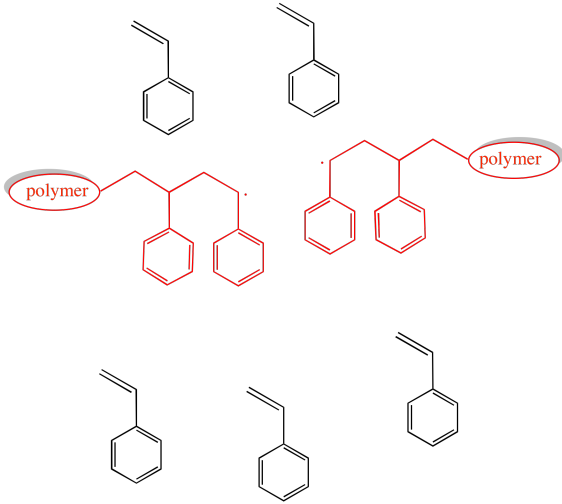

In radical polymerization, growing chains with radicals at their growing ends will be surrounded by monomers. The radicals devour and enchain the monomers as they move through the reaction medium.

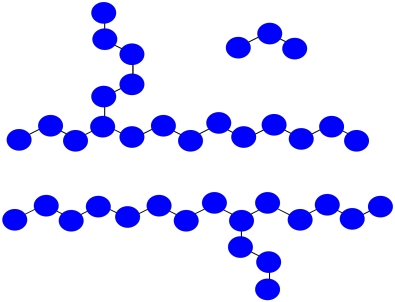

Figure RR10.1. Growing polymer chain ends surrounded by monomers.

Typical chain-terminating events in radical polymerization involve the collision of two growing chains. That event could result in head-to-head radical recombination, formation of a double bond via hydrogen abstraction at the head of a chain ("head biting") or formation of a new radical along the backbone of the polymer ("backbiting").

Problem RR10.4.

Suppose you have three growing polymer chains. The monomers have molecular weight = 100 D. Each chain is currently 8 repeat units long.

a) What is the current molecular weight of each chain?

b) If 15 monomers remain in solution, what is the expected degree of polymerization of each chain, assuming they all grow at the same rate?

c) What is the expected average molecular weight?

d) What is the expected PDI?

e) Suppose two of the chains join together in a termination step. What will be the molecular weight of the new chain?

f) If the third chain keeps growing, what molecular weight will it reach?

g) What will be the average molecular weight?

h) What will be the PDI (assume it's just the ratio of largest to smallest molecular weight)?

Problem RR10.5.

Suppose once again you have three growing polymer chains. The monomers have molecular weight = 100 D. Each chain is currently 8 repeat units long.

This time, one chain abstracts a hydrogen atom from the backbone of another. The first chain is terminated; the second now has two sites of growth. All three sites continue to grow at the same rate.

a) What will be the molecular weight of each chain?

b) What will be the average molecular weight?

c) What will be the PDI (assume it's just the ratio of largest to smallest molecular weight)?

Problem RR10.6.

Practically, polymers are purified by precipitation and washing after they are prepared. That means very short oligomers are washed away.

a) What is the average molecular weight of the impure mixture shown above, assuming each monomer has molecular weight = 100 D?

b) After precipitation and washing, if small oligomers are washed away, what is the avergae molecular weight of the isolated polymer?

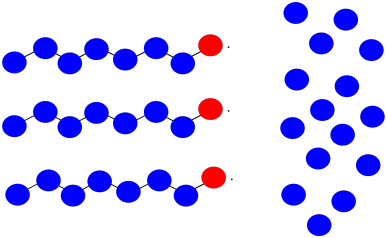

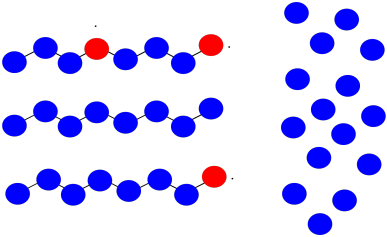

If the concentration of growing chains is limited, then the probability that any of these events will occur is also limited.

Figure RR10.2. The probability of chain termination decreases if the concentration of growing chains decreases.

Certainly, the rate of chain growth also slows when the concentration of growing chains is lowered. That is the price to pay for a smooth operation.

The key to living radical polymerization is to reversibly stop chain growth, sending a polymer chain from an active state into a dormant state. While in the dormant state, the polymer chain is less likely to undergo random chain-termination events. It can't grow, either, until it is brought back into an active state.

Problem RR10.7.

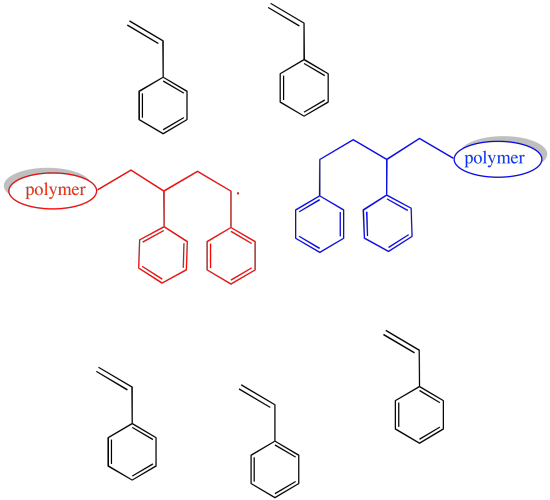

An early attempt at living polymerization employed an alkyl iodide initiator. Thermal initiation (initiation by heating) resulted in a reactive alkyl radical and an iodine atom.

Provide a mechanism for styrene polymerization, making sure to show the following points:

a) initiation

b) propagation

c) recombination with iodine atom

d) a growing chain

e) a "dormant" chain that could re-initiate and start growing again, but which is currently safe from random termination

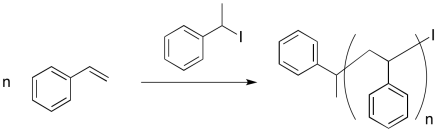

Researchers at IBM found that polystyrene polymerization proceeded much more smoothly when TEMPO, a relatively stable radical, was added to the reaction. The reaction also proceeded more slowly, resulting in overall lower molecular weight of the polymer. However, the distribution of molecular weight was much more uniform. All of the chains were of similar sizes, relatively speaking. As a result, the properties of the material were much more controlled.

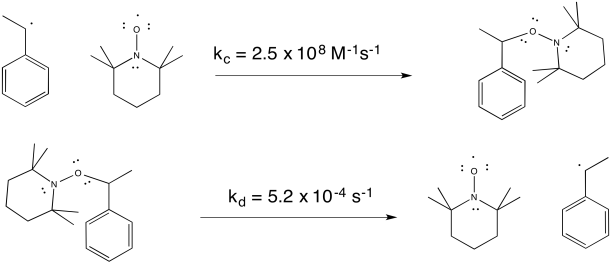

Figure RR10.3. Radical polymerization in the presence of a "chain control agent", RRpolymnLivTEMPO.

TEMPO helps to control the polymerization by forming a reversible bond with the growing end of the polymer chain. The radical on TEMPO combines with the radical on the head of the polymer to form a C-O bond. The bond can break again (unusually, for a C-O bond), allowing the polymer chain to resume growing periodically.

Figure RR10.4. Radical chain ends can be reversibly trapped by TEMPO.

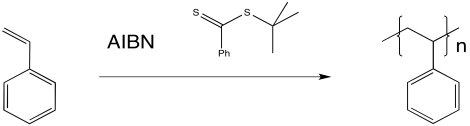

Two of the most common methods of inducing living radical polymerization are RAFT and ATRP. RAFT stands for radical atom fragmentation polymerization. Like the TEMPO reaction, it involves a reversible radical recombination to form a covalent bond. RAFT was developed by a group of Australian chemists in the late 1990's, including Enzio Rizzardo, Graeme Moad and San Thang of Australia's national science agency, CSIRO. ATRP stands for atom-transfer radical polymerization. It was developed in the mid 1990's by Krysztof Matyjaszewski at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh and his post-doctoral associate, Jin-Shan Wang, now at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. An independent discovery of the method was made by Mitsuo Sawamoto at Kyoto University in Japan.

RAFT most commonly employs a thioester (or similar compound) as a chain transfer agent. The chain transfer agent intercepts a growing polymer chain, but does so reversibly.

Figure RR10.5. Radical polymerization in the presence of a RAFT chain control agent.

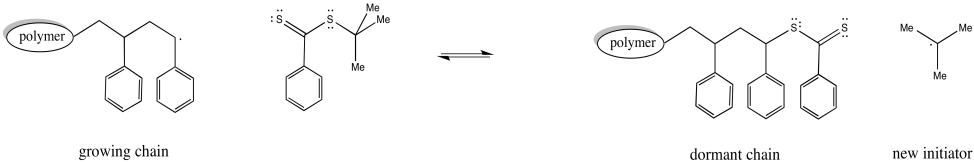

The thioester can react with a radical, placing the growing chain in a dormant state. It can also release a new radical, which can then initiate polymerization. Eventually, it will regulate the growth of two polymer chains.

Figure RR10.6. Chain control equilibrium with RAFT.

In addition, a third species present in equilibrium holds both chains dormant. The chain transfer agent can reversibly release one of these dormant chains at a time.

Problem RR10.8.

Provide a mechanism for conversion of a growing chain into a dormant chain via RAFT.

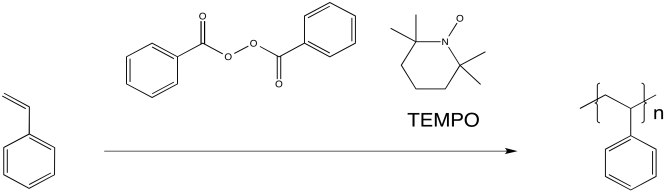

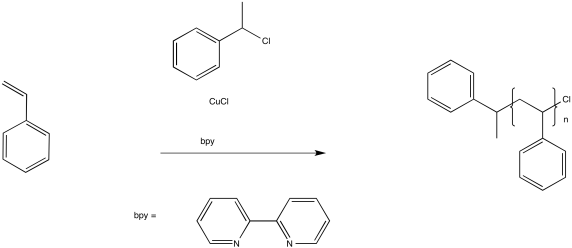

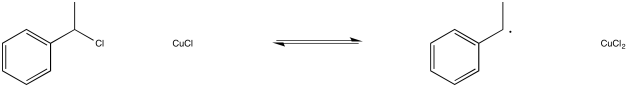

In ATRP, a similar process works to keep a fraction of the chains in a dormant state. A key component of this method is a copper(I) complex.

Figure RR10.7. Radical polymerization in the presence of an ATRP chain control agent.

The role of the copper(I) complex is to transfer an electron to an inactive species, producing a copper(II) species and a radical. For example, in initiation of the reaction above, the Cu(I) transfers an electron to the alkyl halide to become Cu(II). In turn, the chlorine atom on the alkyl halide becomes chloride anion, Cl-, and the alkyl portion is left as an initiating radical.

Figure RR10.8. Initiation in the ATRP system.

One of the reasons ATRP is so important is that it provides a very reliable and inexpensive way to control polymerization. In addition, it can be adapted to a wide range of useful processes. For example, Matyjaszeski has developed methods of electrochemically controlling the reaction; polymerization can literally be turned on and off with a switch. Yusuf Yagci and coworkers at Istanbul Technical University developed a photoinduced ATRP process, in which polymerization begins when the lights come on and stops when it gets dark. Other researchers, including the Hawker lab at UCSB, have also promoted the utility of this approach.

Problem RR10.9.

Provide a mechanism for initiation using ATRP.

Problem RR10.10.

Provide a mechanism for conversion of a growing chain to a dormant chain using ATRP.

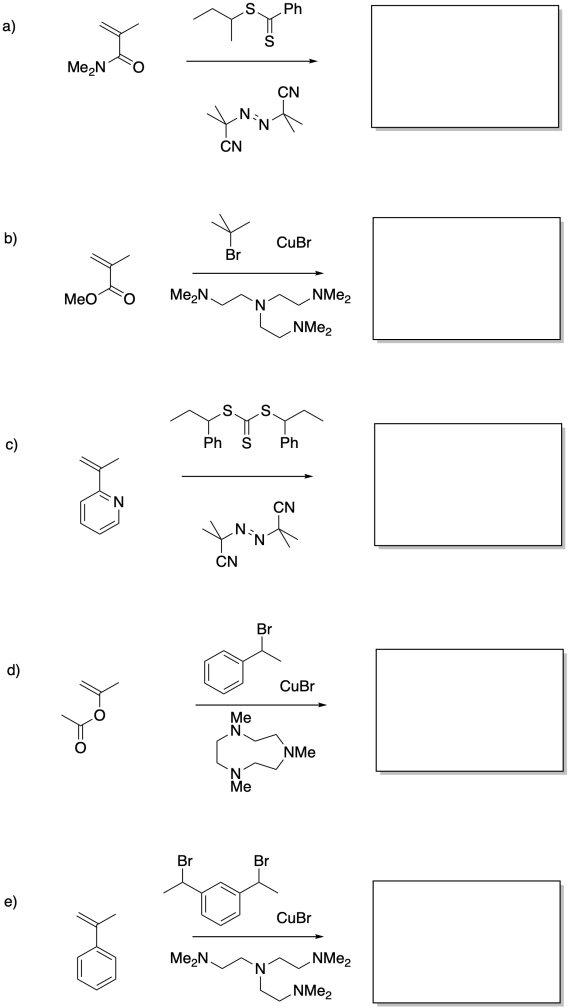

Problem RR10.11.

Provide products of the following reactions.

This site is written and maintained by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with contributions from other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: