03/21/2012

Much of the info presented here comes from ideas presented in a fantastic book written by Lauren Sompayrac, How the Immune System Works. (2003, Blackwell Publishing. ISBN: 0-632-04702-X)

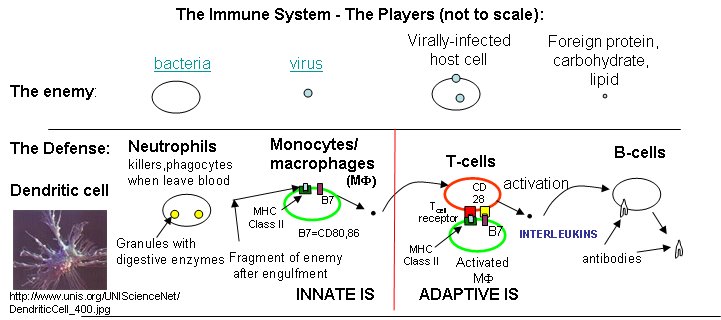

Three lines of defense protect us from the "enemies", foreign substances (bacteria, viruses and their associated proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids) collectively called antigens.

What do B cells and antibodies do? In fact, nothing too exotic. They can't kill anything. B cells make antibodies. Antibodies just bind to foreign molecules (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, etc), which might neutralize their effects, such as binding to the hemagglutinin molecule of the influenza virus and preventing its entry into the cell. They also bind to foreign cells like bacteria which signals other host immune proteins and cells to come in for the kill. Antibodies are secreted by B cells, which also have a membrane bound form of the antibody on their surface. This antibody acts as a receptor which recognizes antigen and through a signal transduction process, helps to activate the B cell. Mature B cells (those that have seen the antigen before) can churn out lots of antibodies quickly. Different surface antibodies, as well as secreted antibodies, can recognize and bind to almost any kind of molecules.

![]() Chime

Model:

Introduction to Antibodies |

Jmol

Chime

Model:

Introduction to Antibodies |

Jmol

![]() Chime

Model:

Antibody

recognition of Antigen |

Jmol

Chime

Model:

Antibody

recognition of Antigen |

Jmol

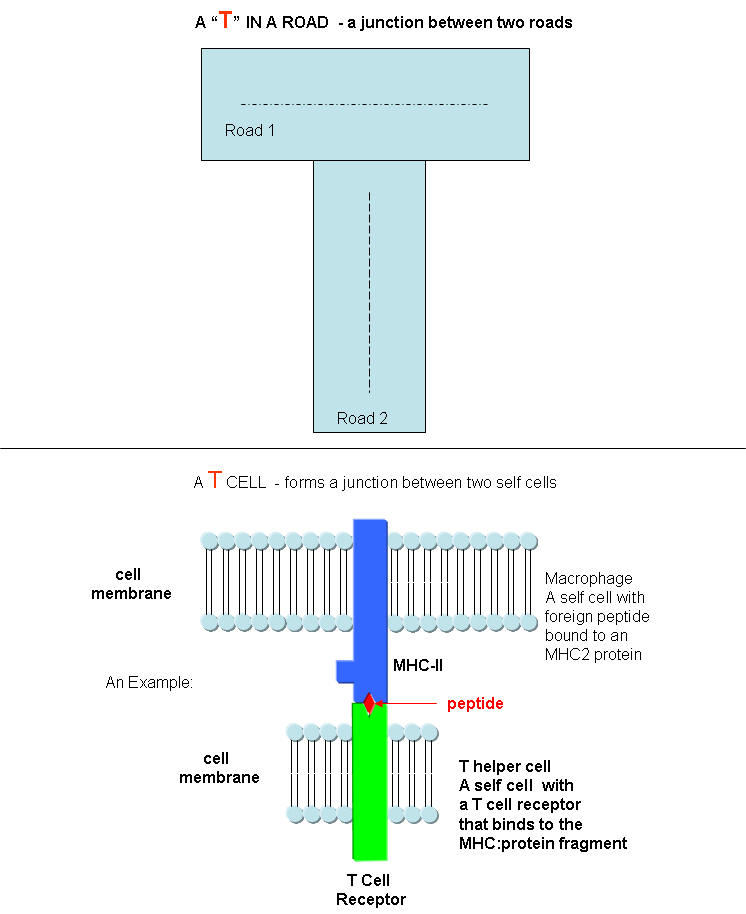

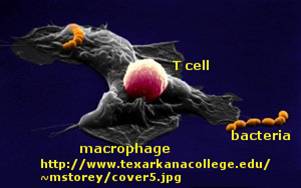

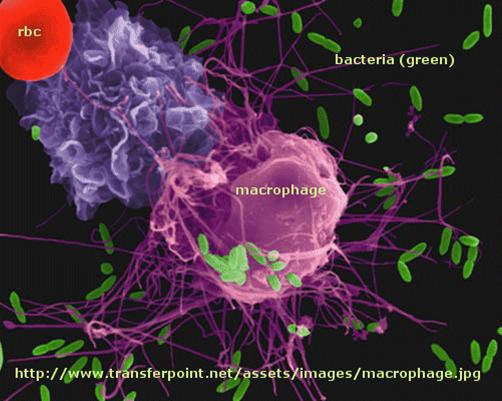

What do T cells do? What happens if a virus makes it into a cell? Antibodies can not bind to them anymore to prevent its entry. Something must be able to recognize a virally-infected cells and eliminate it. What about a cancer cell. Wouldn't it be nice if something could recognize a tumor cell as foreign and eliminate it before it divides to much and metastasizes? That something are T cells. There are many T cells in a person, and many different kinds, including T helper cells (Th) and cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTL).

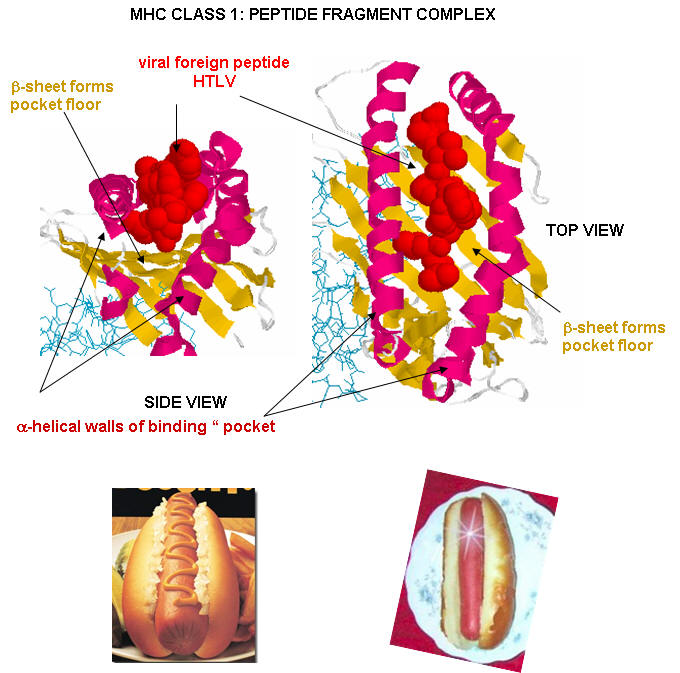

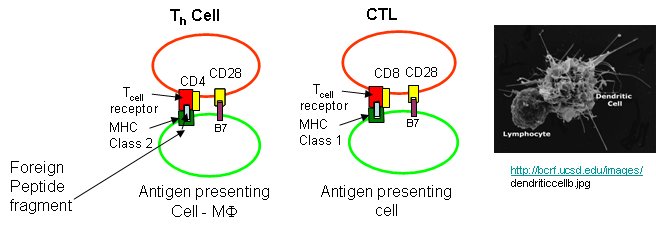

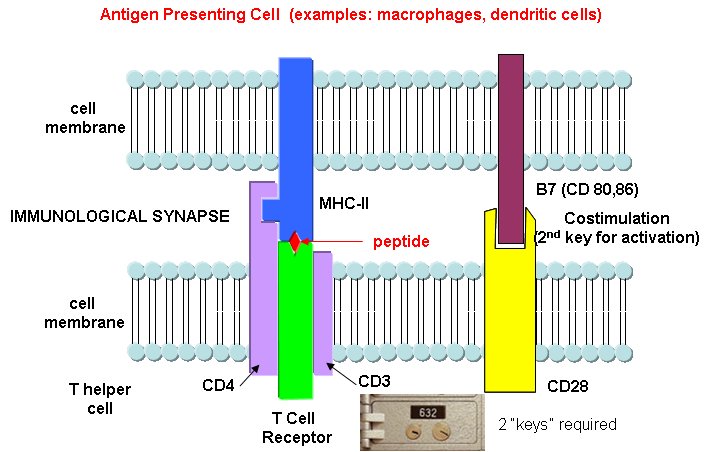

T cells also recognize antigens but unlike B cells, these antigens can only be proteins fragments. The membrane proteins that recognize proteins fragments are call T cell receptors. In addition, they don't recognize protein antigens in isolation. They must be bound to a protein on the surface of an "antigen" presenting cell (such as a macrophage or dendritic cell). The T cell receptor recognizes and binds simultaneously to the foreign protein fragment and to the to the self protein on the surface of the antigen-presenting cells. The self protein which binds and presents the foreign protein fragments (peptides) is called a MHC protein (Major Histocompatability Complex).

Antigen presenting cells like macrophages have MHC Class II molecules on their surface. These bind protein fragments from engulfed bacteria, for example, and present them on the surface. T cell receptors bind to the peptide:MHC II complex. Other cells in the body have MHC Class I proteins on their surface. If a cell is infected with a virus, protein fragments from the virus end up bound to the MHC Class I protein on the surface. Now a T cell can bind through its T cell receptor to the peptide:MHC Class I complex. By displaying a viral protein fragment on the surface, the immune cell can recognize a virally-infected cell without getting inside of the cell where the virus is. Sompayrac describes MHC molecules as looking like a hot dog bun. In the grove of the bun lies the peptide fragment - like the hot dog. The T cell receptor recognizes both the bun and the hot dog!

![]() Chime

Model:

T Cell Receptor: MHCI:

HTLV1 peptide complex (1QSF.pdb)

Chime

Model:

T Cell Receptor: MHCI:

HTLV1 peptide complex (1QSF.pdb)

![]() Chime

Model:

T Cell Receptor: MHCII:

Influenza peptide complex

Chime

Model:

T Cell Receptor: MHCII:

Influenza peptide complex

MHC Class I proteins also present "self" peptides in the binding pocket, since self proteins also are degraded in the cell by proteasomes. However, the T cell receptor does not recognize and bind to the self-peptide fragment bound to the MHC Class 1 protein. Hence T cells do not recognize self and turn against the bodies own cells. Once and a while they do, however, and autoimmune disease like MS, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus result.

Activation of B and T cells: another step

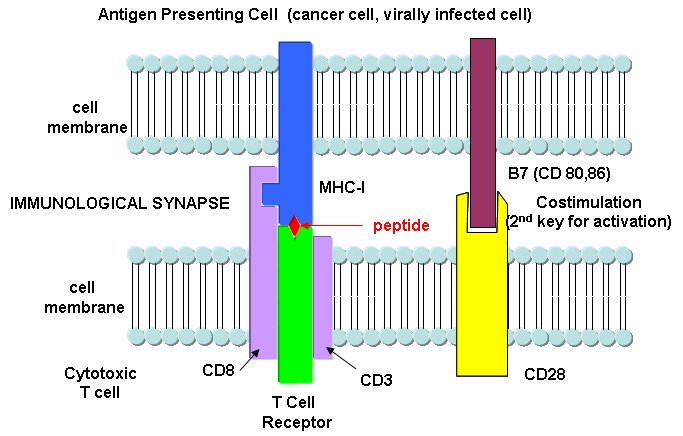

B cells and T cells must be "turned on" before the can do their thing. It is important to regulate the on switch. If the cells were to be become active without need, the cells might turn against self, which would be a big problem. It turns out that it is not enough for the T cell to bind foreign peptide:MHC complexes to get activated. They must bind another protein on the antigen-presenting cell. In the case of T helper cells. a protein on the T cell, CD28, must also bind a protein, B7, on the antigen-presenting macrophage, Hence there is one specific signal (the peptide:MHC complex binding to the T cell receptor) and a nonspecific signal (B7 binding CD28). Why are two signals needed for activation? Again Sompayrac has a great analog - that of a safety deposit box. It takes two keys (a specific key which you own and a nonspecific key (which the bank opens and which opens all the boxes) to open the box. Think of it as double security. You don't want to activate immune cells for killing unless you really need to do so.

Activation of cells either in the innate or adaptive IS occurs through signal transduction processes. Either of two event participate in cell activation:

Which is more important, the innate or adaptive immune system (IS)? Modern thought tilts toward the innate IS. It posts the sentinels. It gets activated when cells detect common pathogens such as bacteria, parasites, and viruses. It then activates the adaptive immune system. We'll first discuss activation of B and T cells in the adaptive immune response, and then return to the initial event, activation of the innate immune system.

Immune cells in action

T cell activation by antigen presenting cells (activated macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells)

Antigen presentation by MHC molecules is a bit complicated.

Class I MHC proteins are found on most human cells. They present peptides (hot dogs) in the grove (buns) of the MHC protein. It turns out that not only are foreign peptides (from virus proteins for example) are presented, but also self peptides. All these peptides are generated by intracellular proteolysis of proteins - self and nonself by a structure in the cell called a proteasome. Sompayrac suggests that the MHC Class 1 proteins are like "billboards [which] advertise a sampling of all the proteins that are being made in a cell". MHC Class 1 molecules present information about proteins made in the cell. They activate CTLs which can kill the altered cell.

Cytotoxic T cells have another protein CD8, which binds to its T cell receptor. The CTL must also have a second nonspecific signaling protein (as mentioned above in the safety deposit box analogy) for cell activation.

Class II MHC proteins are found on immune cells (macrophages, etc) which present antigen to T cells, especially T helper cells. They present information about proteins found outside of the cells (such as on bacteria) but whose proteins might end up inside the antigen presenting cell like a macrophage. They activate T helper cells which, through release of signaling molecules called cytokines, activate other immune cells. B cells, before activation by antigen, express little MHCII proteins (and small amounts of B7). After activation, they express more of these proteins and can activate T helper cells.

T helper cells and CTLs differ in another way. T helper cells have another protein CD4, which binds to its T cell receptor, while CTLs have the protein CD8 bound. Both cells must also have a second nonspecific signaling protein (as mentioned above in the safety deposit box analogy) for cell activation.

Sompayrac asks another interesting question. Why is antigen presentation by MHC proteins necessary at all? B cells don't really need presentation since they can bind antigen with membrane antibody molecules. Why do T cells need it. He gives different reasons for Class I and Class II presentations:

MHC Class I (found on most body cells): T cells need to be able to see what is going on inside the cell. When virally-infected cells bind foreign peptide fragments and present them on the surface, they can be "seen" by the appropriate T cell. It's a way to get a part of the virus, for example, to the surface. They can't hide out in the cell. T cells don't need to recognize extracellular threat since antibodies from B cells can do that. Presentation is also important since viral protein fragments that might be found outside of the cell might bind to the outer surface of a noninfected cell, that would then be targeted for killing by the immune system. That wouldn't be good. It also helps that peptide fragments are presented on the surface. This allows parts of the protein that are buried and not exposed on the surface, which would be hidden from interaction with outside antibodies, to be used in signaling infection of the cell by a virus.

MHC Class II (found on antigen-presenting cells like macrophages): In this way two different cells (the presenting cell and the T helper cell) must interact for a signal for immune system activation to be delivered to the body. Again it is a safety mechanism to prevent nonspecific activation of immune cells. Also, as in the case above, since fragments are presented, more of the foreign "protein" can contribute to the signal to activate the immune system.

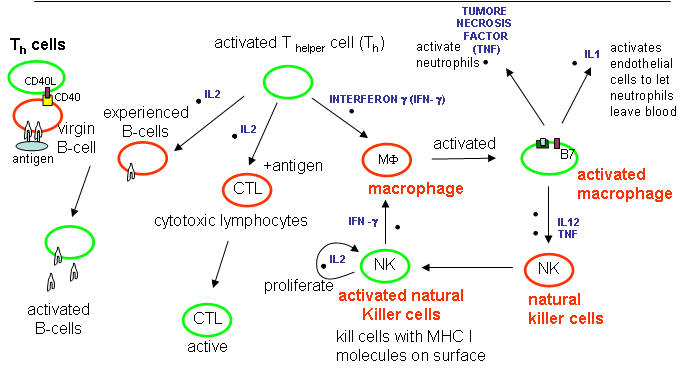

Cytokines and Activation of Immune Cells

There are a large number of different cytokines that are released from immune cells. Some examples and their activities are shown in the diagram below and described in the text that follows. They are

Cytokines released from cells such as macrohages in the innate IS:

Tumor Necrosis Factor: TNF - from activated macrophages and dendritic cells. Main mediator of acute inflammation. Induces fever and sleep by acting on sites in the brain. Promote scar formation (excessive wound healing). Too much can cause shock. Acts on

endothelial cells that line all blood vessel walls, and facilitates the movement of immune cells from the blood into tissues through the endothelial cells.

activates neutrophils

activates macrophages which leads to IL1 secretion

kills some tumor cells.

IL-1 - has similar properties as TNF

IL-12 - Activates NK and CTL. Leads to release of INF-γ from NK and T cells.

Interferon α, β, ω : Are produced by virally-infected cells. They cause cells to degrade mRNA which kills virally-infected cells. The enzyme involved in RNA hydrolysis is inactive until the cell becomes infected with a virus. This protects uninfected cells.

Cytokines released after antigen activation of T cells in the adaptive immune system:

IL-2 -

Produced by T helper cells (CD4), and leads to the proliferation of NK cells and T and B-lymphocytes that have been activated by antigen exposure.

Interferon-gamma (INF-γ) -

is also produced by activated T cells and increases the activity of other T cells (CTLs, NK cells.

principle way to activate macrophages.

induces expression of MHC-I molecules, MHC-II molecules on antigen presenting cells to promote presentation

IFN-γ stimulates the differentiation of T4-lymphocytes into activated T helper cells.

Chemokines

Chemokines are chemotactic cytokines, or protein that recruit other cells towards the site of release. Some examples are listed below:

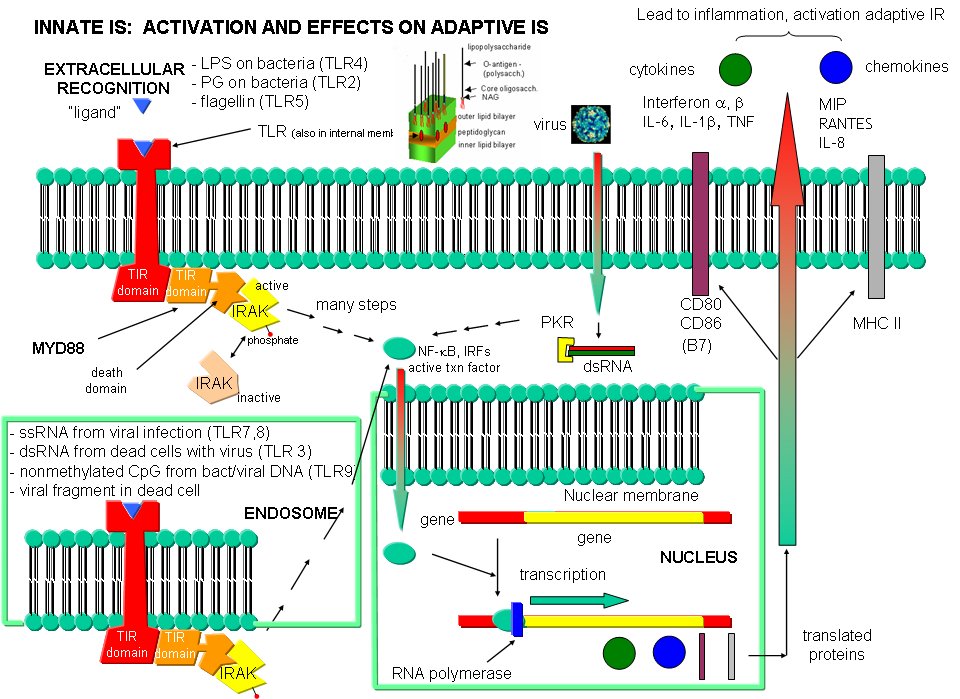

Back to the Innate Immune System

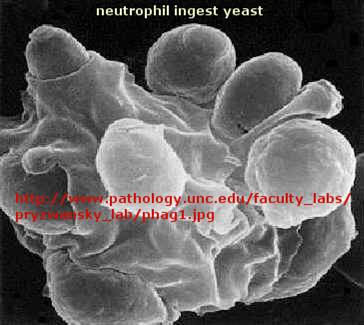

The adaptive immune response must be activated by cells on the innate immune system. These cells must recognized viruses and living cells like bacteria, fungi, and protozoans like amoebas. There are often common structural features in these different classes of cells. The cells of the innate system (dendritic cells, macrophages, eosinophils, etc) have receptors (Toll-like Receptors 1-10 or TLRs) that recognize the common pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) , which leads to binding, engulfment, signal transduction, maturation (differentiation), antigen presentation, and cytokine/chemokine release from these cells. Take for example dendritic cells, which reside in the peripheral tissues and act as sentinels. They can bind PAMPs which include:

Bacterial and viral nucleic acids are recognized by intracellular TLRs in the cell after the they been taken up into the cells by endocytosis. Dendritic cells phagocytize microbial and host cells killed through programmed cell death (apoptosis). In the process of maturation, surface protein expression is altered, allowing the cells to leave the peripheral tissue and migrate to the lymph nodes where they activate T cells through the antigen presentation methods described above. They also control lymphocyte movement through release of chemokines. The very large figure below shows the processes involved in recognition of PAMPs by TLRs of innate immune system cells.

Some great links:

Cytokines

New: Cytokine storm