Reactivity in Chemistry

Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution

AR2. Mechanism of Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution

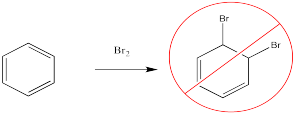

Bromine will not add across the double bond of benzene.

Figure AR2.1. The failure of electrophiles to add across the double bond of benzene.

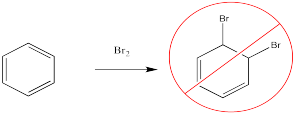

Instead, a bromine atom can replace one of the hydrogen atoms on the benzene. Instead of adding Br2 across the double bond, giving one Br at each end of the carbob-carbon bond in place of the former double bond in the product, a bromine atom has substituted for a hydrogen atom. This reaction is especially easy in the presence of a catalyst. The catalyst can be as simple as iron metal, but usually an Fe3+ or Fe(III) salt is used, such as FeBr3 or FeCl3.

Figure AR2.2. An electrophile substitutes for a hydrogen atom on benzene.

How does that outcome happen? Why does that outcome happen?

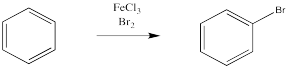

There has been a good deal of study of these reactions and there is strong evidence of the steps through which they occur. As expected, the reaction involves donation of π electrons from the benzene. The benzene has lots of π electrons. It is electron-rich, so it is a good source of electrons. For the moment, we'll assume the electrophile is a bromine cation; it probably isn't really Br+, but we will deal with its exact structure later when we look at how electrophiles form in these reactions.

Figure AR2.3. Substitution for hydrogen on aromatic rings requires very strong electrophiles.

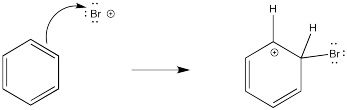

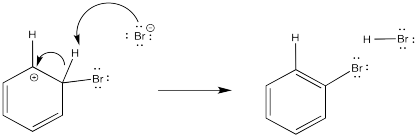

It makes sense that a Br+ (if it existed) would attract electrons from anywhere it could. The problem is, that initial step results in the loss of aromaticity. The aromatic system confers a little extra stability on the π system, so the molecule is motivated to restore the aromaticity. The easiest way to do that, and get rid of a positive charge at the same time, would be to deprotonate the cation. Some base will pick up the proton. The base could be anything with a lone pair that would be capable of binding a proton; it is likely a bromide ion in this case. We will see later where that bromide comes from.

Figure AR2.4. Deprotonation of the arenium ion intermediate.

How do we know that the mechanism unfolds this way? There are three basic steps that are clearly accomplished during the course of the reaction: the C-H bond is broken, the C-Br bond is formed, and the Br-Br bond is broken.

When is the C-H bond broken? That question can be answered by looking for what is called an "isotope effect". The most common isotope of hydrogen is 1H, or protium, but 2H is also available; it is called "deuterium". Deuterium is often represented by the symbol D and protium by the symbol H. Deuterium is twice as heavy as the common protium. That mass difference leads to a lower vibrational frequency of a C-D bond than a C-H bond. The C-H bond vibrates more rapidly and energetically than a C-D bond; as a consequence, the C-H bond is more easily broken than the C-D bond.

If we take a sample of ordinary benzene, C6H6, and a sample of deuterated benzene, C6D6, we can measure how quickly they each undergo a bromination reaction. Very often, a reaction that involves C-H bond cleavage will slow down if a C-D bond is involved. This outcome is observed in E2 eliminations, for instance. This slowing of the reaction with the heavier isotope is called the deuterium isotope effect.

However, no deuterium isotope effect is observed during bromination, or other aromatic electrophilic substitution reactions. That absence of an isotope effect usually means the C-H bond cleavage is a sort of an afterthought. The hard part of the reaction is already done. Both the C-H and C-D bonds are broken so quickly and easily, by comparison, that we don't really notice the difference between them.

There is even more evidence. In a few exceptional cases, the cationic intermediate in this reaction is stable enough to be isolated and crystallized. X-ray diffraction shows that there is a tetrahedral carbon in the ring, indicating that the C-H bond has not broken yet.

The C-H bond is broken at the end of the reaction. When is the Br-Br bond broken?

That question is a little harder to answer. We can't use the same isotope strategy that we used with the C-H bond. Although deuterium is twice as heavy as protium, producing a substantial isotope effect, 81Br is only 2.5% more massive than 79Br. Any difference in rates involving these isotopes is undetectable. The exact nature of the bromine species in the reaction is complicated, and may even be different under different conditions.

Problem AR2.1.

In the case of uncatalyzed bromination reactions, the addition of salts such as NaBr has no effect on the reaction rate, indicating that the arene reacts directly with Br2 rather than Br+. Explain this line of reasoning.

Problem AR2.2.

Given each of the following electrophiles, provide a mechanism for electrophilic aromatic substitution.

a) NO2+ b) CH3CH2+ c) SO3H+ d) CH3CO+

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: