Reactivity in Chemistry

Reduction & Oxidation Reactions

RO4. Reduction Potential and Energy Levels

Reduction potentials are relative. Standard reduction potentials are reported relative to the reduction of protons in a standard hydrogen electrode (SHE). But what would we see if we used some other sort of electrode for comparison?

For example, instead of a hydrogen electrode, we might use a fluorine electrode, in which we have fluoride salts and fluorine gas in solution with a platinum electrode. (Maybe we just don't think working with hydrogen is dangerous enough.)

The "reduction potentials" we measure would all be relative to this reaction now. They would tell us: how much more motivated is this ion to gain an electron than fluorine?

The resulting table would look something like this:

Table RO4.1. A table of reduction potentials standardized to the reduction of F2 rather than the reduction of H+.

| Half Reaction (species are aqueous unless noted otherwise) | Potential, Volts, Relative to Fluorine Reduction |

| Li+ + e- → Li (s) | - 5.91 |

| Al(OH)3(s) + 3e- → Al(s) + 3OH- | - 5.18 |

| Sc3+ + 3e- → Sc (s) | - 4.95 |

| Al3+ + 3e- → Al (s) | - 4.53 |

| V2+ + 2e- → V (s) | - 4.00 |

| Zn2+ + 2e- → Zn (s) | - 3.632 |

| Fe2+ + 2e- → Fe (s) | - 3.31 |

| CO2(g) + 2H+ + 2 e- → CO(g) + H2O | - 2.98 |

| Cu+ + e- → Cu (s) | - 2.98 |

| 2 H+ + 2 e- → H2(g) | - 2.87 |

| Fe3O4(s) + 8 H+ + 8 e- → 3Fe(s) + 4 H2O | - 2.79 |

| Cu2+ + 2e- → Cu0 | - 2.53 |

| CO(g) + 2H+ + 2 e- → C(s) + H2O | - 2.35 |

| MnO4- + 2 H2O + 3e- → MnO2(s) + 4 OH- | - 2.28 |

| Fe3+ + e- → Fe2+ | - 2.10 |

| Ag+ + e- → Ag (s) | - 2.074 |

| MnO2 + 4 H+ + 2e- → Mn2+ + 2 H2O | - 1.64 |

| MnO4- + 4 H+ + 3e- → MnO2(s) + 2 H2O | - 1.17 |

| Au+ + e- → Au (s) | - 1.04 |

| F2 (g) + 2e- → 2F- | 0.00 |

The trouble is, there isn't much out there that would be more motivated than fluorine to gain an electron. All of the potentials in the table are negative because none of the species on the left could take an electron away from fluoride ion. However, if we turned each of these reactions around, the potentials would all become positive. That means gold, for instance, could give an electron to fluorine to become Au(I). This electron transfer would be spontaneous, and a voltmeter in the circuit between the gold electrode and the fluorine electrode would measure a voltage of 1.04 V.

That potential is generated by the reaction:

2Au (s) + F2 (g) → 2Au+ + 2F-

Notice that, because 2 electrons are needed to reduce the fluorine to fluoride, and because gold only supplies one electron, two atoms of gold would be needed to supply enough electrons.

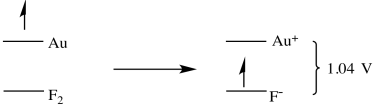

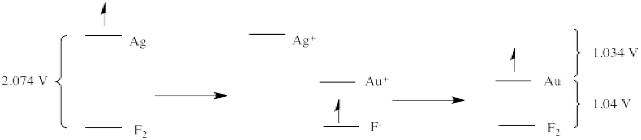

The reduction potentials in the table are, indirectly, an index of differences in electronic energy levels. The electron on gold is at a higher energy level than if it were on fluoride. It is thus motivated to spontaneously transfer to the fluorine atom, generating a potential in the circuit of 1.04V.

Figure RO4.1. The relative energy of an electron on gold and an electron on fluorine.

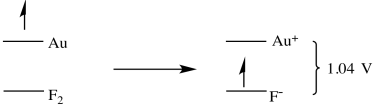

Silver metal is even more motivated to donate an electron to fluorine. An electron from silver can "fall" even further than an electron from gold, to a lower energy level on fluoride. The potential in that case would be 2.074 V.

Figure RO4.2. The relative energy of an electron on silver and an electron on fluorine.

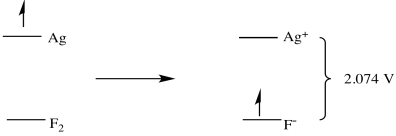

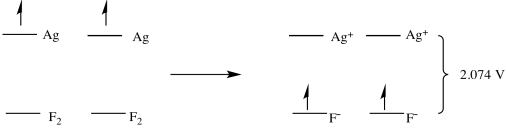

There are a couple of things to note here. The first is that, if potential is an index of the relative energy level of an electron, it doesn't matter whether one electron or two is transferred. They are transferred from the same, first energy level to the same, second energy level. The distance that the electron falls is the same regardless of the number of electrons that fall. A reduction potential reflects an inherent property of the material and does not depend on how many electrons are being transferred.

Figure RO4.3. Reduction potential is an intensive property. It does not depend on the number of moles.

Another important note is that, if reduction potentials provide a glimpse of electronic energy levels, we may be able to deduce new relationships from previous information. For example, if an electron on gold is 1.04 V above an electron on fluoride, and an electron on silver is 2.074 V above an electron on fluoride, what can we deduce about the relative energy levels of an electron on silver vs. gold?

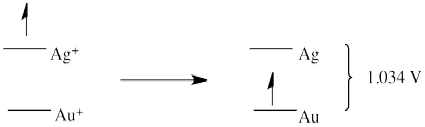

The answer is that the electron on silver is 1.034 V above the electron on gold. We know this because reduction potentials are "state functions", reflecting an intrinsic property of a material. It doesn't matter how we get from one place to another; the answer will always be the same. That means that if we transfer an electron from silver to gold indirectly, via fluorine, the overall potential will be the same as if we transfer the electron directly from silver to gold. So, the electron drops from silver to fluorine (a drop of 2.074 V). The electron then hops (under duress) up to gold (a climb of 1.04 V). The net drop is only 1.034 V.

Figure RO4.4. Different reduction potentials can be combined to obtain new reduction potentials.

That's the same value we would expect to measure if we took a standard solution of gold salts and a gold electrode and connected it, via a circuit, to a standard solution of silver salts and a silver electrode.

Figure RO4.5. The relative energy of an electron on silver and an electron on gold, obtained by comparing both with fluorine.

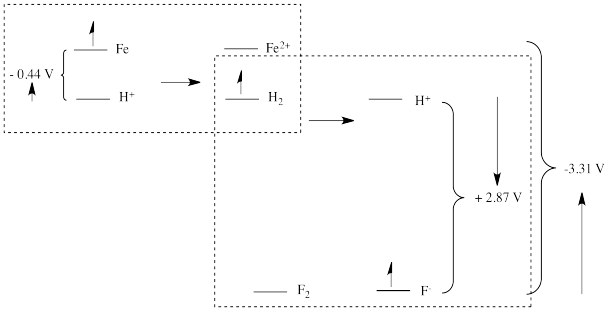

In fact, the table above doesn't reflect any experimental measurements; it's simply the table of standard reduction potentials from the previous page, with the reduction potential of fluorine subtracted from all the other values.

Figure RO4.6. Combining the reduction potential of iron with the reduction potential of fluorine to obtain the potential for the reduction of fluorine by iron.

In other words, mapping out the distance from iron to SHE (in terms of the reduction potential for Fe2+ + 2 e- → Fe(s)), together with the distance from SHE to fluorine gives the potential relative to IFE (imaginary fluorine electrode).

Problem RO4.1.

a) Show an energy diagram showing the relative energy levels when an electron is transferred from silver to gold(I) ion. What is the potential for this reaction?

b) Show an energy diagram showing the relative energy levels when an electron is transferred from copper to silver(I) ion. What is the potential for this reaction?

c) Show how the results of (a) and (b) can be used to determine the potential for the transfer of an electron from copper to gold(I) ion.

Problem RO4.2.

Frequently in biology, electron transfers are made more efficient through a series of smaller drops rather than one big jump. To think about this, consider the transfer of an electron from lithium to fluorine. (Neither of these species is likely to be found in an organism, but this transfer is a good illustration of a big energy difference.)

a) Write an equation for this reaction.

b) What would be the potential for this reaction?

c) This is a highly exothermic reaction; however, our imaginary organism that attempts to harness this reaction as an energy source is likely to burst into flames every time the reaction occurs. Comment on the organism's Darwinian fate.

d) Propose, instead, a series of reactions that the organism could use to slow down the release of energy. Suppose the organism, apart from fluorine and lithium, also harbors reserves of scandium(III), silver(I), copper(I), vanadium(II) and gold(I).

Show an energy diagram for this series of reactions and label the potential for each step.

e) Explain why this approach would more efficiently harness the energy of lithium's electron.

Problem RO4.3.

An "activity series" is a ranking of elements in terms of their "activity" or their ability to provide electrons. The series is normally written in a column, with the strongest reducing metals at the top. Beside these elements, we write the ion produced when the metal loses its electron(s). Looking at the table of reduction potentials relative to fluorine on this page, construct an activity series for the available elements.

Problem RO4.4.

Construct an activity series for the alkali metals using the following standard reduction potentials (relative to SHE): Fr, -2.9 V; Cs, -3.026 V; Rb, -2.98 V; K, -2.931 V; Na, -2.71 V; Li, -3.04 V.

Problem RO4.5.

In reality, the energy gap that leads to a reduction potential is sometimes more complicated than following an electron as it moves from one level to another. Use the activity series you have constructed for the alkali metals to compare and contrast the redox potential with your expectations of energy level / ease of electron donation based on standard periodic trends.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted on individual pages. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic,

Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by

Chris Schaller

is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: