Reactivity in Chemistry

Thermodynamics

TD5. Reversibility and le Chatelier

Sometimes, there is not a big difference in energy between reactants and products of a reaction. What happens then? Does the reaction go forward, because it will not cost a lot of energy? Or does it not proceed, because there isn't enough driving force?

For example, one simple reaction that occurs all the time is the reaction of water with carbon dioxide. This is a reaction that happens when carbon dioxide dissolves in lakes, rivers and oceans. It even happens in your own bloodstream.

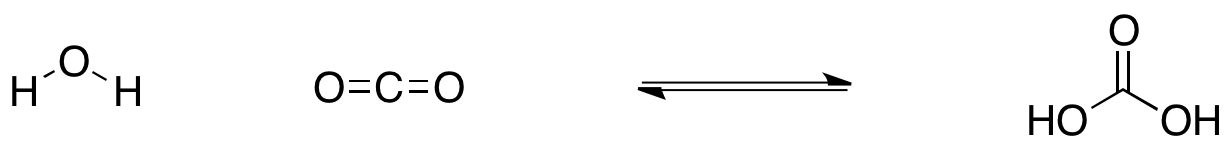

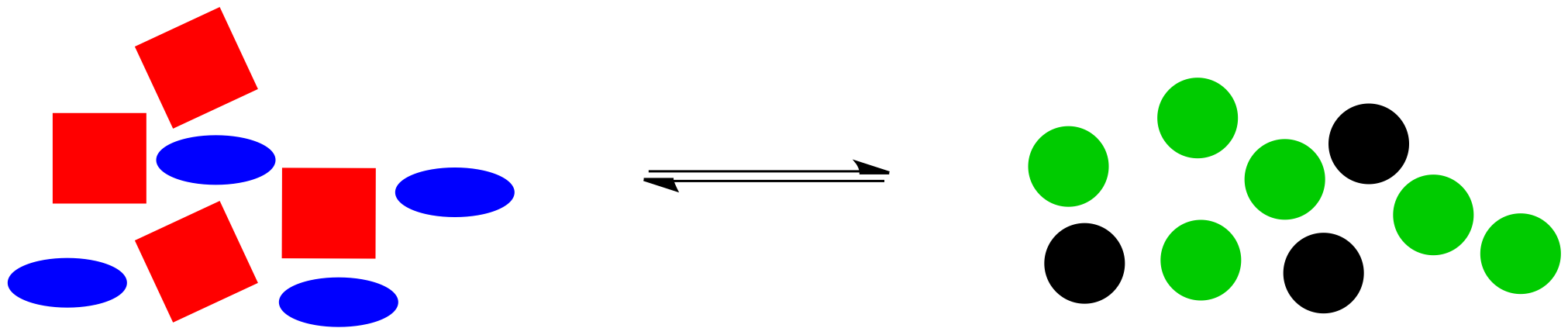

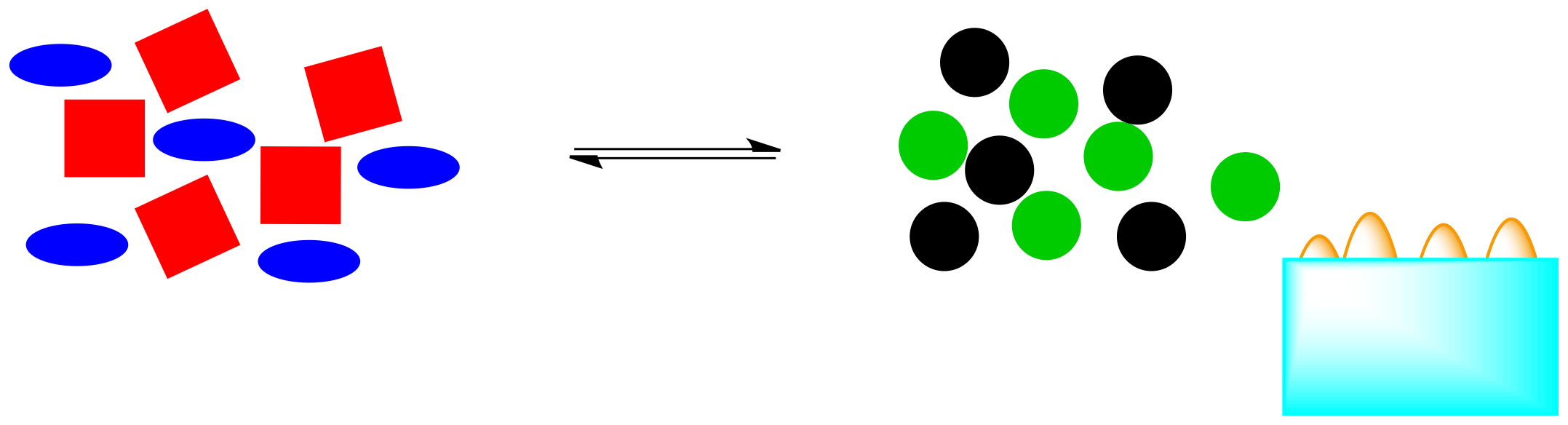

Figure TD5.1. Equilibrium between water plus carbon dioxide on the left and carbonic acid on the right.

Water reacts with carbon dioxide to form carbonic acid. However, carbonic acid also decomposes spontaneously in water. It reacts to form carbon dioxide and water.

In other words, this is a reaction that can go either direction. It can go forwards or backwards. It is an example of an equilibrium reaction. An equilibrium reaction is one that is energetically balanced, so that it really isn't favoured to go in either direction.

Equilibrium reactions are extremely important in nature, partly because of the forward and reverse capabilities that they offer. In essence, they are reactions with an "undo" button. The reaction can proceed in one direction when needed, and it can proceed in the other direction when needed.

However, there are some inherent limitations involved. Frequently, equilibrium reactions only proceed "partway". That is, a group of molecules will start to produce products. However, at some point those products will begin reverting to the starting materials again. Eventually the system will settle out as a mixture of reactants and products.

What if it's really important that we have the products of the reaction at one point, with none of the reactants? And if later on we need the reactants, but not any of the products? It would be useful if there were a way to control the direction of an equilibrium reaction, so that we could "push" it to one side or the other.

Control of equilibrium reactions can be remarkably simple. It follows a rule that was observed by Henri le Chatelier (ah-REE luh shah-tell-YAY), a French industrial chemist, around 1900. Le Chaletelier noticed that equilibrium reactions often shift direction if the conditions of the reaction are changed.

In general, adding any product of the reaction shifts the balance back toward the reactants. If any product of the reaction is added, the reaction makes more starting materials. Thus, adding more carbonic acid to a carbon dioxide - water - carbonic acid mixture would result in reverse reaction, producing more water and carbon dioxide. Adding more carbon dioxide, on the other hand, would lead to production of more carbonic acid.

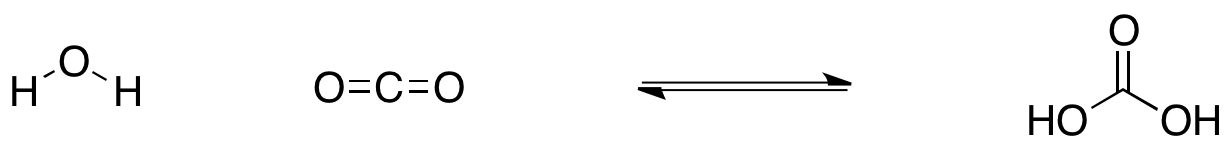

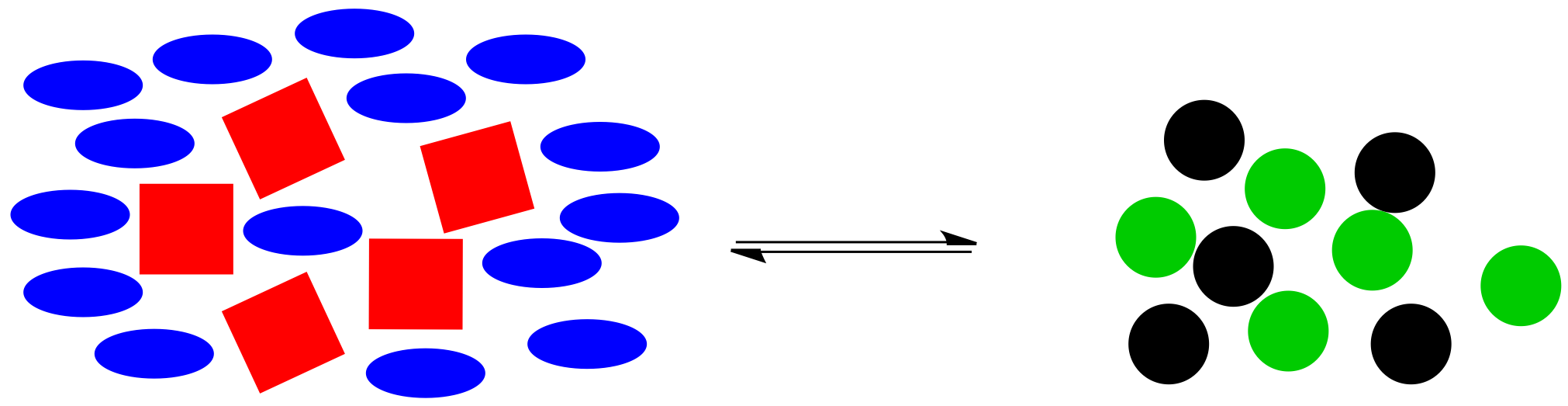

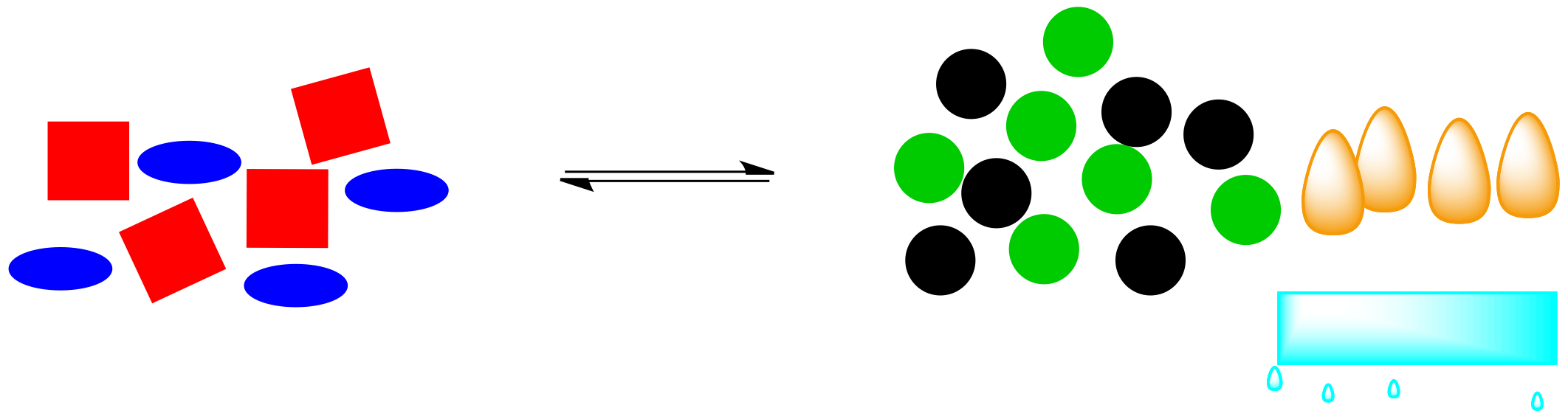

Here is a cartoon illustration of "le Chatelier's Principle" at work. Suppose red squares and blue ovals can react together to make black circles and green circles. Maybe there is a natural equilibrium in this reaction, so that the two piles of shapes are roughly equal in size.

Figure TD5.2. An equilibrium in a generic reaction.

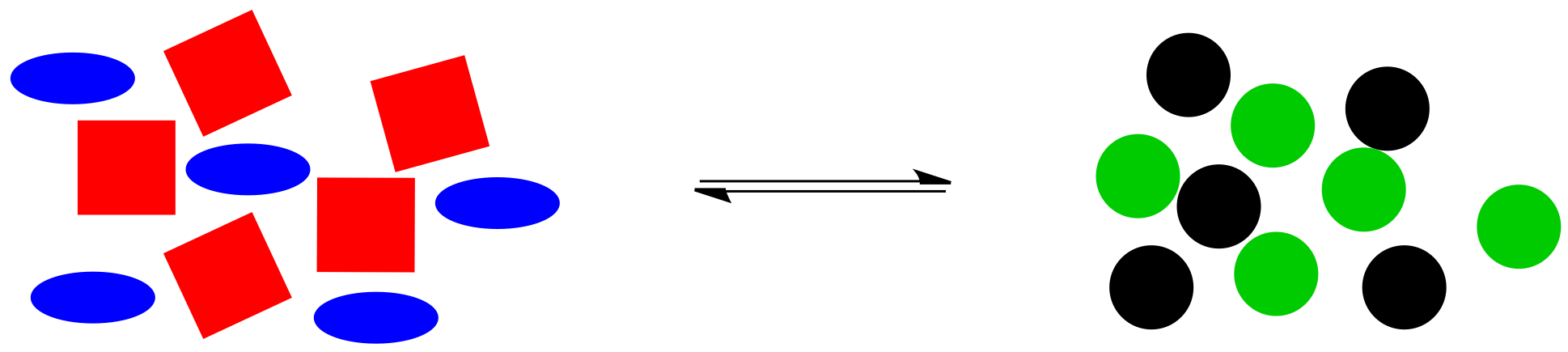

What would happen if something knocked this system off balance? For example, maybe black circles are highly volatile, and they float away through the air as soon as they are formed. The system won't be in equilibrium anymore, because some of those black circles will be gone. Without those black circles, the balance will be upset, with not enough things on the right side for the number of things on the left.

Figure TD5.3. The same equilibrium but some of the black molecules are lost to the gas phase.

Le Chatelier noticed that nature automatically corrects for such changes. If some of the black circles disappear, the reaction will kick into action again, using up some red squares and blue ellipses to produce more green and black circles. The exact numbers of shapes won't return to exactly the same as before, because some of the black circles have still gone missing, but the system will have shifted to use up more reactants on the left and to produce more products on the right, so that the overall ratio between right and left is restored.

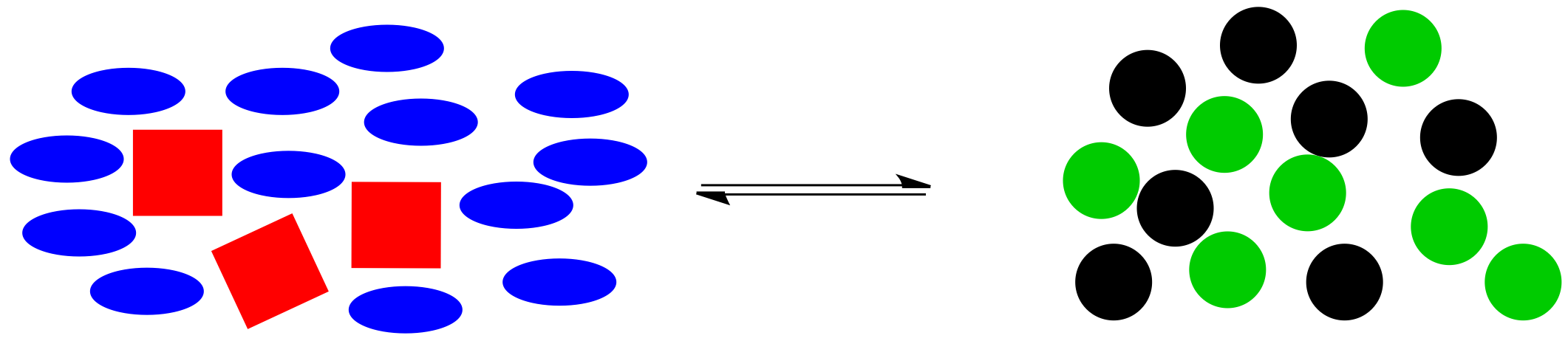

Figure TD5.4. Equilibrium shifts to the right, consuming more blue and red molecules to replace the lost black ones.

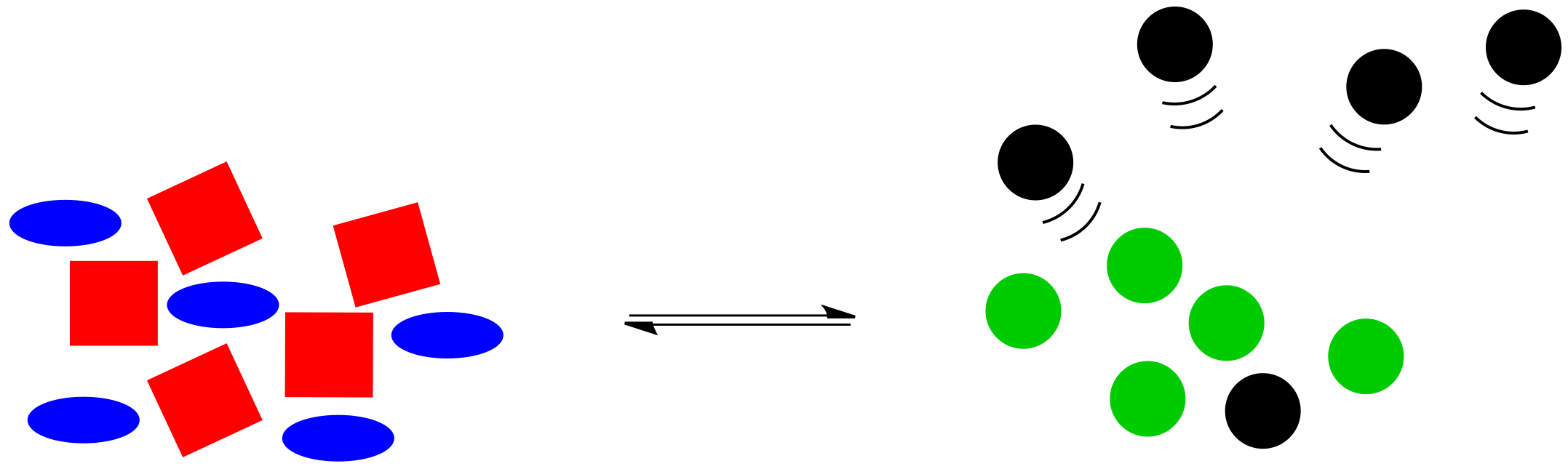

Alternatively, maybe we found a way to make the black circles stay where they are. Instead, we have dumped in a bunch of extra blue ellipses. Once again, the system is knocked off balance. This time, there is too much stuff on the left, compared to the amount on the right side.

Figure TD5.5. Equilibrium is disturbed when a bunch of blue molecules are added suddenly.

The reaction goes into action again. It uses up some of those extra blue ellipses (and, at the same time, some of the red squares) to produce more black and green circles, bringing the system back to the original ratio of right side shapes to left side shapes.

Figure TD5.6. Equilibrium shifts to the right to consume some of the extra blue molecules.

In general, if molecules are added to a system, the reaction will shift to bring the system back into equilibrium. If molecules are removed from the system, the reaction will also shift to bring the system back into equilibrium.

Furthermore, because heat can be consumed by (or produced by) reactions, temperature can sometimes be used to shift equilibria. If a reaction is exothermic, heat is a product of the reaction. Adding more heat will result in the reaction shifting to prooduce more reactants. Cooling the reaction (removing heat) would do the opposite: the reaction would shift to produce more heat, and more products.

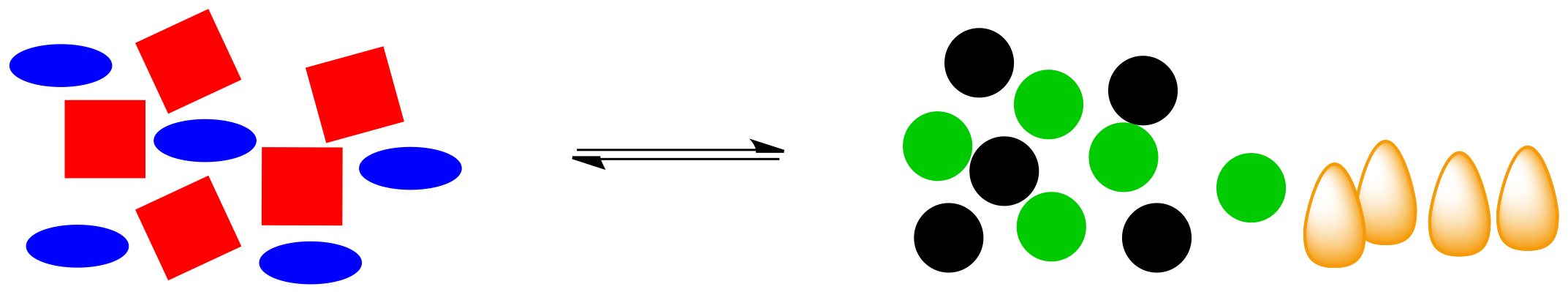

In the cartoon, we have a shape-shifting reaction again, but this time the reaction releases energy (those are orange flames, symbolic of the heat produced).

Figure TD5.7. An exothermic reaction produces heat as well as product molecules.

What happens if that energy is removed? For example, if heat is removed through addition of a pale blue ice cube, what will be the effect on the system?

Figure TD5.8. If an exothermic reaction is cooled, some of the heat will be consumed.

Those orange energy shapes (the "flames") were a part of the system. If they are removed, the system will have to shift in order to restore them. If the reaction pushes to the right again, more energy will be released, bringing the system back into equilibrium.

Figure TD5.9. The equilibrium shifts to produce more heat and more product molecules.

Problem TD5.1.

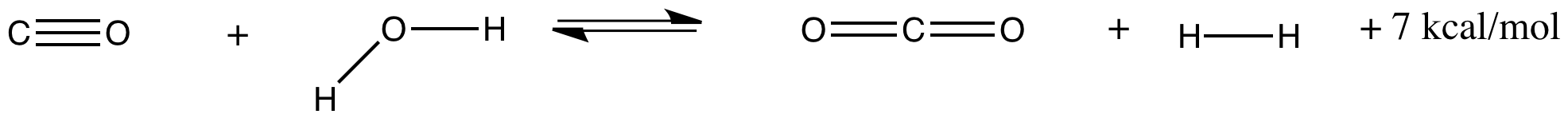

The water-gas shift reaction involves the production of hydrogen gas from steam and carbon monoxide. It is important both for the commercial production of hydrogen gas and for its application in fuel cells. At 300 K, the reaction (and an approximte energy produced) is shown below:

Explain what would happen if this gas-phase reaction is already at equilibrium and the following changes take place:

a) The pressure of steam injected into the reaction is doubled.

b) The temperature is raised to 450 K.

c) The CO2 produced is "captured" and removed as carbonate.

d) The temperature is lowered to 250 K.

e) The pressure of CO added is cut in half.

Problem TD5.2.

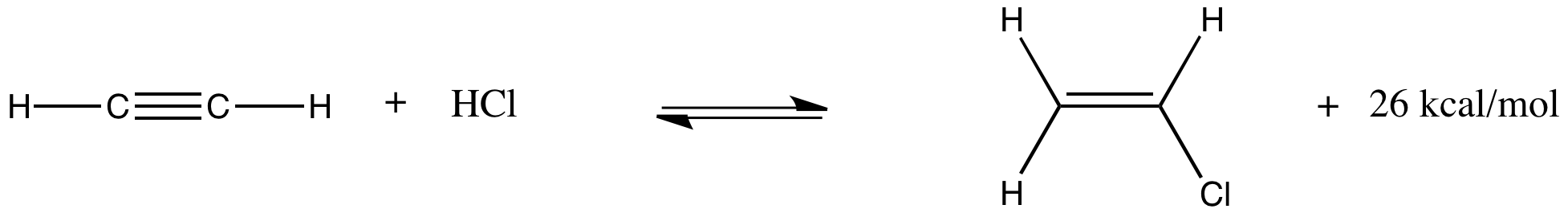

Hydrochlorination of acetylene (ethyne) is another gas-phase reaction. It is used to produce vinyl chloride, the starting material for the polyvinyl chloride commonly used to make the pipes in household plumbing. At 300 K, the reaction (and an approximate energy produced) is shown below:

Explain what would happen if the system is at equilibrium and the following changes take place:

a) The temperature is raised to 350 K.

b) The pressure of HCl is doubled.

c) The pressure of acetylene is cut in half.

d) The temperature is dropped to 250 K.

e) The overall pressure in the system is increased from one atmosphere to two atmospheres.

Problem TD5.3.

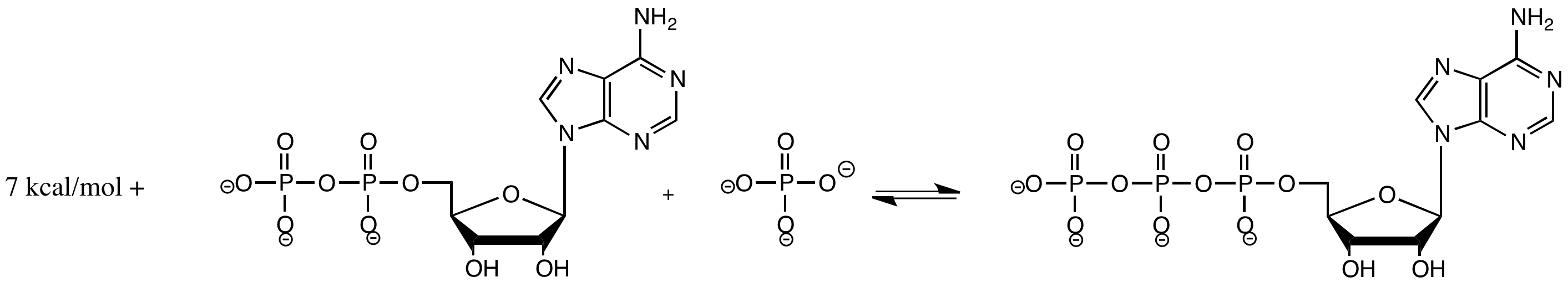

Production of ATP in the cell proceeds according to the reaction below, with an approximate energy indicated at 310 K.

If the system is already at equilibrium, explain what happens when the following changes take place:

a) The temperature is raised to 320 K (It's OK. This organism is really hardy and it can handle the temperature change).

b) The temperature is lowered to 300 K.

c) The supply of inorganic phosphate is doubled.

Problem TD5.4.

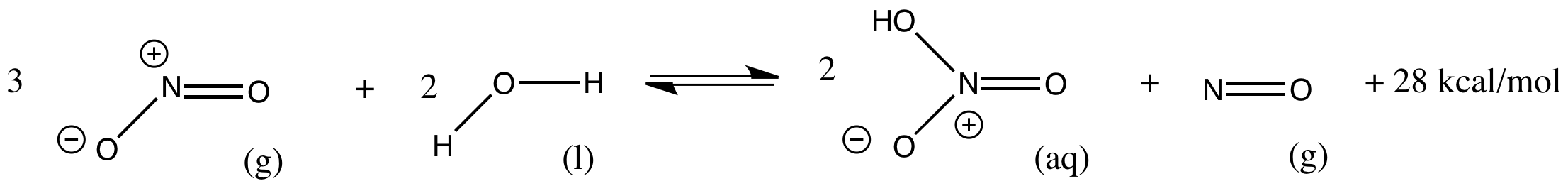

Nitric acid, HNO3, is a common industrial chemical. For example, it is used to make azo dyes that are employed in paints. Nitric acid production involves the following reaction, with an approximate energy change indicated at 300 K.

Note that this is a multi-phase reaction: it involves gases (g), liquids (l) and aqueous solutions (aq, something dissolved in water). Explain what would happen if production were run under the following conditions:

a) The NO2 gas is introduced into a chamber that contains a tank of water. After reacting for a while, the gas is released and the water, containing the aqueous solution of nitric acid, is drained from the tank.

b) The NO2 gas is introduced into a chamber that contains a tank of water. Periodically, the water is drained from the tank, and new water is introduced, without releasing any gases.

c) The NO2 gas is continually introduced into a chamber, and there is a vent that slowly releases gases from the chamber at all times. There is also a constant flow of water into and out of the chamber.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted on individual pages. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and

Inorganic Chemistry by

Chris Schaller is licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation:

Back to Web Materials on Structure & Reactivity in Chemistry