Reactivity in Chemistry

Thermodynamics

TD4. Free Energy

Entropy and enthalpy are two of the basic factors of thermodynamics. Enthalpy has something to do with the energetic content of a system or a molecule. Entropy has something to do with how that energy is stored.

There is a bias in nature toward decreasing enthalpy in a system. Reactions can happen when enthalpy is transferred to the surroundings.

A reaction is favoured if enthalpy decreases.

There is also a bias in nature toward increasing entropy in a system. Reactions can happen when entropy increases.

A reaction is favoured if entropy increases.

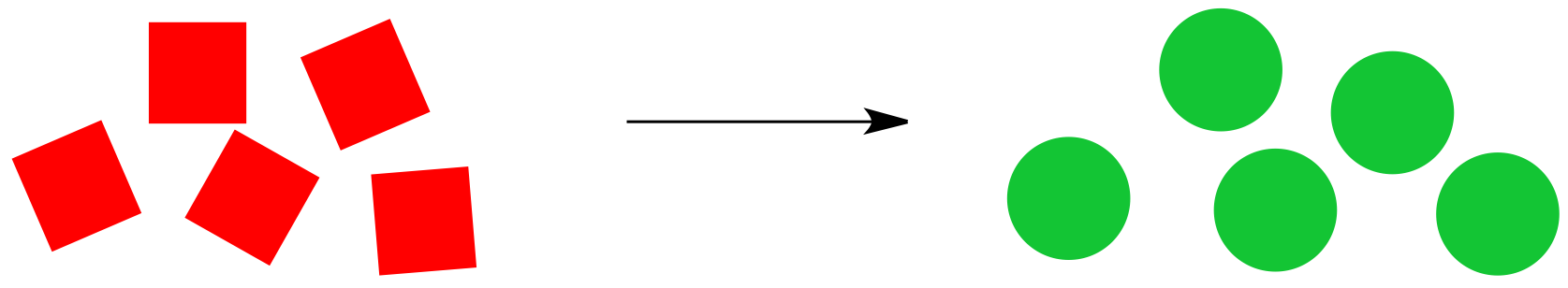

Consider the cartoon reaction below. Red squares are being converted to green circles, provided the reaction proceeds from left to right as shown.

Figure TD4.1. A cartoon for a generic reaction.

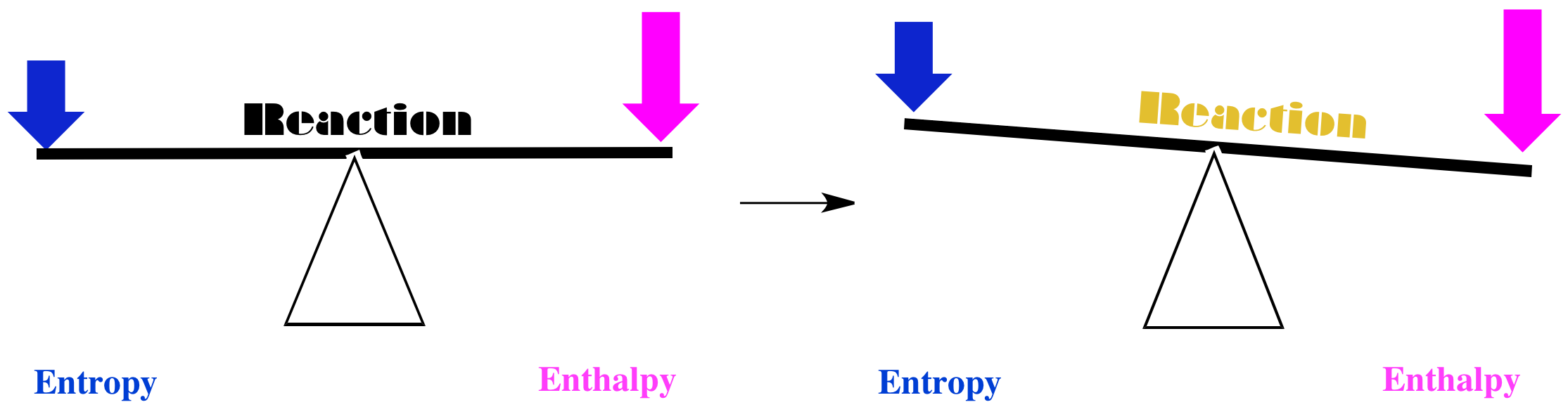

Whether or not the reaction proceeds to the right depends on the balance between enthalpy and entropy. There are several combinations possible.

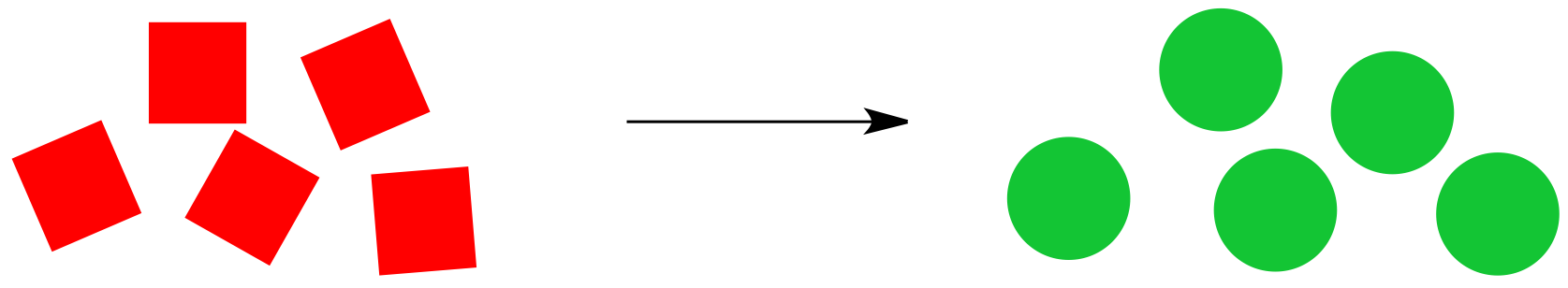

In one case, maybe entropy increases when the red squares turn into green circles, and the enthalpy decreases. If we think of the balance between these two factors, we come to a simple conlusion. Both factors tilt the balance of the reaction to the right. In this case, the red squares will be converted into green circles.

Figure TD4.1. Reactions are driven forward if entropy increases and enthalpy decreases.

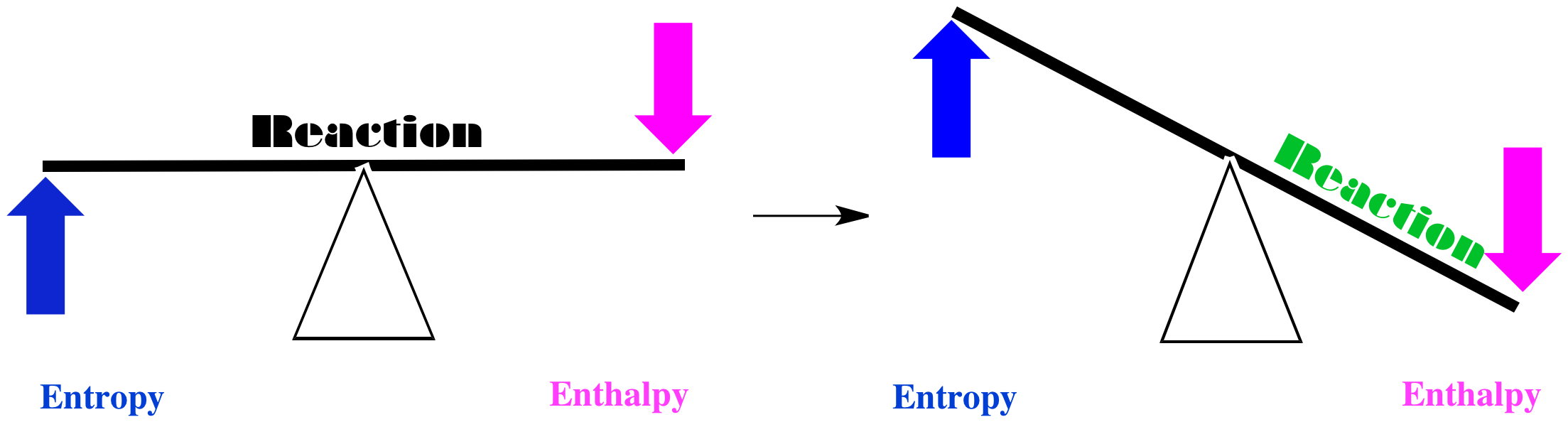

Alternatively, maybe entropy decreases when the red squares turn into green circles, and enthalpy increases. If we think of the balance between these two factors, we come to another simple conlusion. Both factors tilt the balance of the reaction to the left. In this case, the red squares will remain just as they are.

Figure TD4.2. Reactions are driven backward if entropy decreases and enthalpy increases.

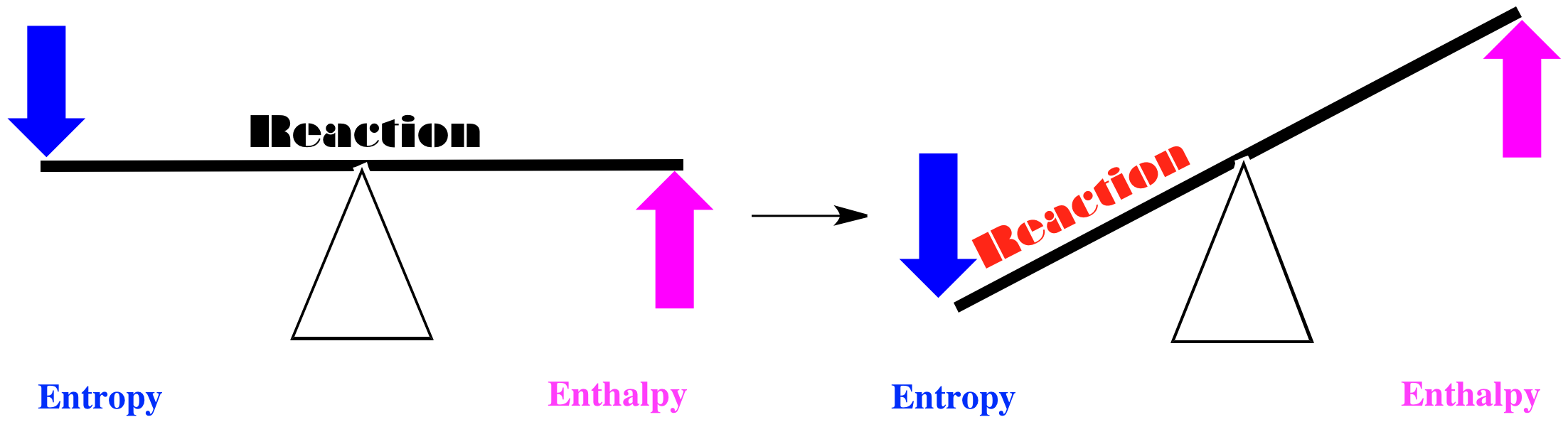

Those two cases are pretty straightforward. However, having two factors to consider can always lead to complications. For example, what if enthalpy decreases, but so does entropy? Does the reaction happen, or doesn't it?

In that case, we may need quantitation to make a decision. How much does the enthalpy decrease? How much does the entropy decrease? If the effect of the enthalpy decrease is greater than that of the entropy decrease, the reaction may still go forward.

Figure TD4.3. Things are much more subtle if both entropy and enthalpy decrease (or they both increase).

The combined effects of enthalpy and entropy are often combined in what is called "free energy". Free energy is just a way to keep track of the sum of the two effects. Mathematically, the symbol for the internal enthalpy change is " ΔH" and the symbol for the internal entropy change is "ΔS". Free energy is symbolized by "ΔG", and the relationship is given by the following expression:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

(note: that may look like "?G" = "?H" - "?S" in some web browsers, rather than DG = DH - TDS; the ? will show up as a Greek delta in Safari or Firefox)

The letter T in this expression stands for the temperature (in Kelvin, rather than Celsius or Fahrenheit). The temperature acts as a scaling factor in the expression, putting the entropy and enthalpy on equivalent footing so that their effects can be compared directly.

How do we use free energy? It works the same way we were using enthalpy earlier (that's why the free energy has the same sign as the enthalpy in the mathematical expression, whereas the entropy has an opposite sign). If free energy decreases, the reaction can proceed. If the free energy increases, the reaction can't proceed.

A reaction is favoured if the free energy of the system decreases.

A reaction is not favoured if the free energy of the system increases.

Because free energy takes into consideration both the enthalpy and entropy changes, we don't have to consider anything else to decide if the reaction occurs. Both factors have already been taken into account.

Remember the terms "endothermic" and "exothermic" from our discussion of enthalpy. Exothermic reactions were favoures (in which enthalpy decreases). Endothermic ones were not. In free energy terms, we say that exergonic reactions are favoured (in which free energy decreases). Endergonic ones (in which free energy increases) are not.

Problem TD4.1.

Imagine a reaction in which the effects of enthalpy and entropy are opposite and almost equally balanced, so that there is no preference for whether the reaction proceeds or not. Looking at the expression for free energy, how do you think the situation will change under the following conditions:

a) the temperature is very cold (0.09 K)

b) the temperature is very warm (500 K)

Problem TD4.2.

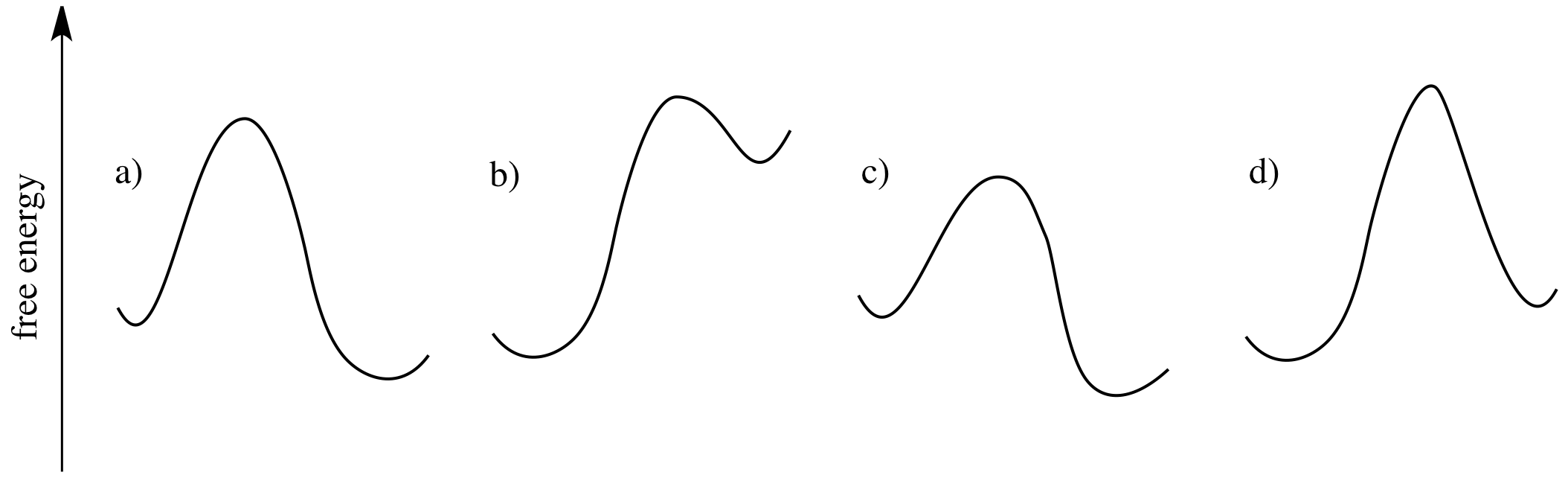

Which of the following reaction profiles describe reactions that will proceed? Which ones describe reactions that will not proceed?

How Entropy Rules Thermodynamics

Sometimes it is said that entropy governs the universe.

As it happens, enthalpy and entropy changes in a reaction are partly related to each other. The reason for this relationship is that if energy is added to or released from the system, it has to be partitioned into new states. Thus, an enthalpy change can also have an effect on entropy.

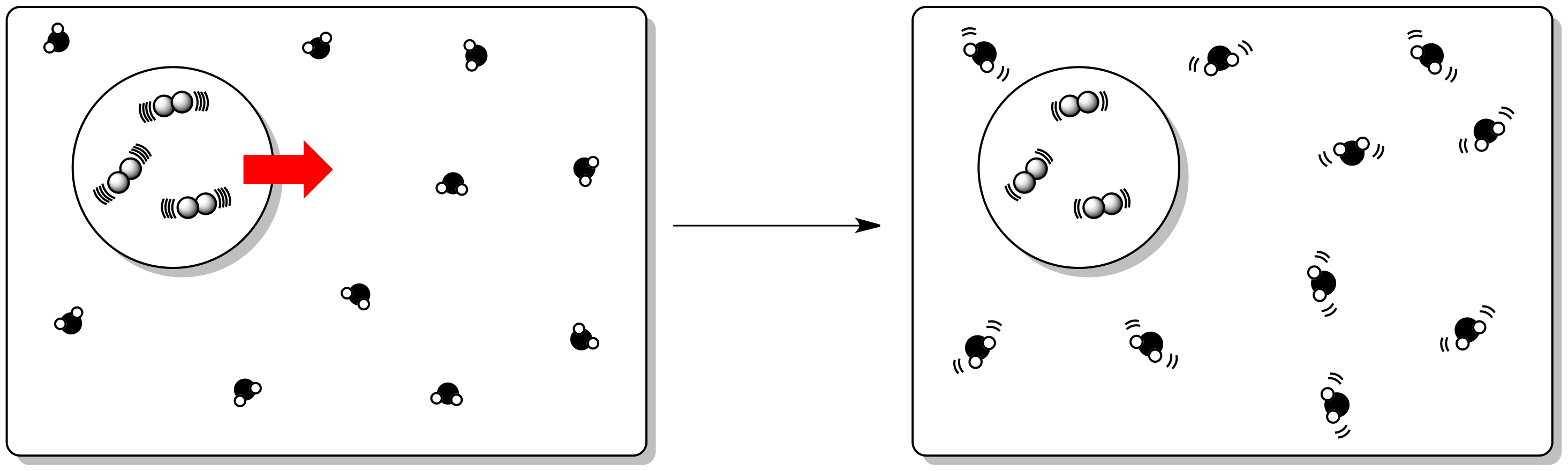

Figure TD4.4. An exothermic reaction releases its energy to the surroundings.

Specifically, the internal enthalpy change that we discussed earlier has an effect on the entropy of the surroundings. So far, we have just considered internal entropy changes.

In an exothermic reaction, the external entropy (entropy of the surroundings) increases.

In an endothermic reaction, the external entropy (entropy of the surroundings) decreases.

Free energy takes into account both the entropy of the system and the entropy changes that arise because of heat exchange with the surroundings. Together, the system and the surroundings are called "the universe". That's because the system is just everything involved in the reaction, and the surroundings are everything that isn't involved in the reaction.

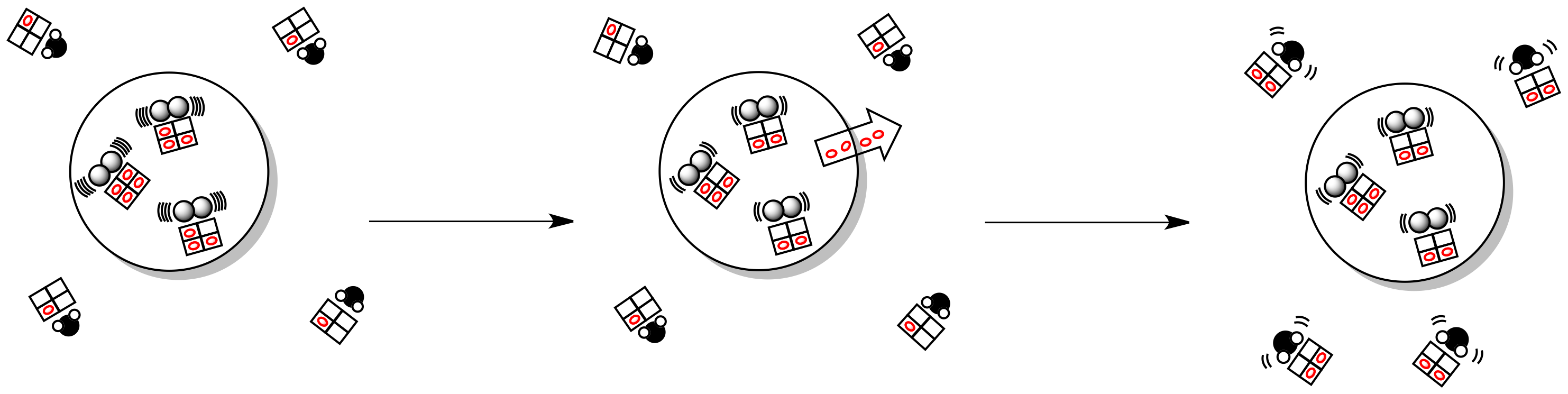

Enthalpy changes in the system lead to additional partitioning of energy. We might visualize that with the mailbox analogy we used for entropy earlier. In this case, each molecule has its own set of mailboxes, into which it sorts incoming energy.

Figure TD4.5. An exothermic reaction increases the entropy of the surroundings.

Looked at in this way, thermodynamics boils down to one major consideration, and that is the combined entropy of both the system and its surroundings (together known as the universe).

For a reaction to proceed, the entropy of the universe must increase.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted on individual pages. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and

Inorganic Chemistry by

Chris Schaller is licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation:

Back to Web Materials on Structure & Reactivity in Chemistry