PLEASE BOOKMARK THIS PAGE

PLEASE BOOKMARK THIS PAGE

|

|

|

The Colonel

What you have heard is true. I was in his house. His wife carried a tray of coffee and sugar. His daughter filed her nails, his son went out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on its black cord over the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English. Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to scoop the kneecaps from a man’s legs or cut his hands to lace. On the windows there were gratings like those in liquor stores. We had dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief commercial in Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was some talk then of how difficult it had become to govern. The parrot said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck themselves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

May 1978

Theme 3: Poems about Family Relationships

Source |

POET |

POEM |

Father/Mother/Siblings |

| Amniocentesis | Amniocentesis | ||

| *Peacock p.126f | Komunyakaa, Yusef | My Father's Loveletters | Father/ Son/ Mother (divorced) triangle |

| *Peacock p.128f | Ondaatje, Michael | Letters & Other Worlds | Father in his fear, desire to articulate, letters; alcoholic (cf. papa's waltz) |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 23 | Blok, Aleksandr | The Vulture | Mother and her baby son: "Grow and suffer, son" (Also about War ) |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 5 | Andrade, Carlos Drummond de | Travelling in the Family | Son to dead father - why were you silent? |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 127 | Hesiod | from THEOGENY: The Great Father Eating His Children | The great Kronos waiting to eat the children being born of Rheia |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 128 | Olds, Sharon | Saturn | he crunched the torso of his child, showing the son what a man's life is |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 129 | Olds, Sharon | The Guild | Young man sitting next to father learning cruelty and oblivion to pass on to next generation |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 130 | Roethke, Theodore | My Papa's Waltz | My Papa's Waltz Such waltzing was not easy |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 135 | Rumi | The Core of Masculinity | Pray for a tough instructor |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 137 | Lee, Li-Young | The Gift | Metal splinter -- I was seven when my father took my hand like this |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 138 | Lee, Li-Young | The Weight of Sweetness | father - son carrying peaches, son left behind SEE THINGS |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 141 | Hayden, Robert | Those Winter Sundays | What did I know of love's austere and lonely offices? |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 145 | Vallejo, Cesar | The Distant Footsteps | Father Sleeping in the parlor (Dying?) I am bitterness, distance, broken, descending, creaking |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 38 | Lee, Li-Young | A Story | Not being able to tell a son a story! Silence |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 41 | Joyce, James | On the Beach at Fontana | I wrap him warm.. In my heart how deep unending Ache of love! |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 46 | Madhubuti | Men and Birth: The Unexplainable | New Men present at birth, source of love and undying commitment.. |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 49 | Snyder, Gary | Changing Diapers | You and me and Geronimo are men |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 55 | Williams, William Carlos | The Turtle | I see the great turtle my son does |

| *Rag and Bone Shop 60 | Rilke | Sometimes a Man Stands up During Supper | children

and their fathers...The church in the East

|

|

|

Monday, February 28

|

Readings for Monday: __ two poems from our Rag and Bone anthology -- Theodore Roethke's "My Papa's Waltz," p. 130; and Robert Hayden's "Those Winter Sundays," p. 141. __Please purchase the Vintage Anthology from the bookstore and choose a poet you would like to work on. In class you will set up a time to meet with your small group to narrow your choice to one poet by Wednesday. __ We will have a somewhat shorter class again on Monday (we will meet until noon), but you can use the extra time to meet with your group if you are ready to discuss your choices |

Writing for Monday. __ Write an entry on either Roethke's or Hayden's poem. Please use the number 11 to start your subject line for easier reference, like this: 11. (Roethke or Hayden) // (Your Title) __ If you have the inclination, feel free to scour the net for images or biographical items about either Roethke or Hayden which we can use for class. Simply do an extra entry if you would like to alert us to some good source(s). |

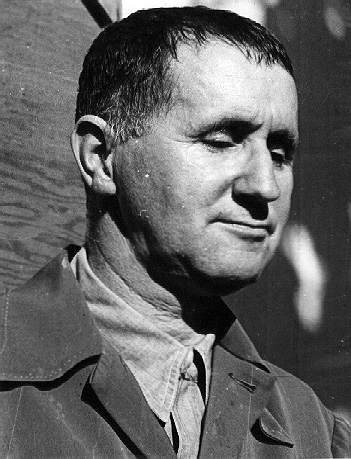

Theodore

Roethke

Robert Hayden

"My Papa's Waltz"

"Those Winter Sundays"

Wednesday,

|

For Wednesday: __ Listen to the cassette tape handed out in class featuring the voices and poetry of Sandra McPherson and Linda McCarriston __ Time permitting, do some browsing on the web or in the library for images and biographical information on either Sandra McPherson or Linda McCarriston.

|

Writing for Wednesday: __ Write out in an entry -- as well as you can -- one of the poems by either Sandra McPherson or Linda McCarriston which you found most poignant in your listening to the tape. Then write an entry -- a line-by-line explication in a kind of reader-response is often the most effective and adequate approach to poems like this. Make sure you explore well beyond a simple paraphrase for each line, talking about the inner tensions of the poem, the ambiguities, and how you are forced to change your mind at every step along the way. Quote the text and pay close attention to the sounds of the words and how these sounds coincide or clash with the apparent sentence and line meaning. 12. (McPherson or McCarriston) // (A Title for Your Entry Which Helps Tease Us into Reading What You Have to Say)

|

Linda McCarriston

Sandra McPherson

"To Judge Faylan,

"One Way She Spoke to Me"

Dead Long Enough

"Bad Mother Blues"

A Summons"

"HELEN TODD: My Birthname"

Friday |

Writing for Friday, March 3: __Do a line-by- line explication of one of the following poems. *Rag and Bone Shop 127 Hesiod *Rag and Bone Shop 128 Olds, Sharon *Rag and Bone Shop 129 Olds, Sharon *Rag and Bone Shop 135 Rumi *Rag and Bone Shop 137 Lee, Li-Young *Rag and Bone Shop 38 Lee, Li-Young *Rag and Bone Shop 46 Madhubuti *Rag and Bone Shop 55 Williams, William Carlos 13. Poet's Name // Your Title

|

|

Reading for Tuesday: On Tuesday we will be hosting the Argentinian speaking poet, Gustavo Fontan in the first part of the class hour. Please read the following two short poems several times through and come with two questions for our guest. Scott has typed out the poems with their English translations here.

Rastros del Ausente / Traces of the Absent One 1 La noche horada su vientre. The night pierces its womb.

2 Las estrellas comportan un h�bito en la noche. The stars bear a custom in the night.

|

Writing for Tuesday: __Do a line-by- line explication of one of the following poems. *Rag and Bone Shop 127 Hesiod *Rag and Bone Shop 128 Olds, Sharon *Rag and Bone Shop 129 Olds, Sharon *Rag and Bone Shop 135 Rumi *Rag and Bone Shop 137 Lee, Li-Young *Rag and Bone Shop 38 Lee, Li-Young *Rag and Bone Shop 46 Madhubuti *Rag and Bone Shop 55 Williams, William Carlos 14. (Hesiod, Olds, Lee, Rumi, Madhubuti, Williams) // (Your Title) __ If you have time: Write a brief entry on one of Fontan's poems, "Traces of the Absent One," 1 & 2, shown here in the left column. (optional) 14.5 Fontan // Your Title |

Tuesday |

Writing for Tuesday, March 7. __Write an entry on another ONE of the poems listed above, this time choose just five lines from the poem and do a very close reading -- recording your impressions, thoughts, feelings, comparisons as you read from word to word. Do you think of other poems or literary works as you enter a particular image or ponder the poet's use of a particular word? Which single word strikes you most in these lines? 14 (Hesiod, Olds, Lee, Rumi, Madhubuti, Williams) // (Your Title)

|

Monday |

Gustavo Fontan was excited about meeting you -- he was still

pondering your questions later in the day. Thank you for showing him your good

hospitality! April Bernard will be meeting with Sr. Mara's class Thursday at 11:20, so won't be able to meet with us at that time. Professor Cindy Malone is in charge of her schedule until Friday should you like to meet with her individually or in a small group. Feel free to e-mail or call Cindy Malone if you are excited about this. Wednesday afternoon after 2 and Friday morning look quite open on April Bernard's schedule. Here's a bit more about her ... http://www.csbsju.edu/insidebooks/writer2.htm Your first draft of a 3-5 page paper on a Vintage poet is due March 15 (at least three of the poet's poems will be featured in your paper). Please meet with your small group to debate through each poem of your poet in preparation for writing. You may wish to meet during our regular Thursday time. Your group should sign up for a specific class period soon for your presentation, which should be completed by March 31. On April 7th we will have a mini-midterm which will give you the opportunity to review and rethink what you have learned so far. The first part will ask you to ponder in writing Rilke's Letters, Peacock's first two chapters, and Hirsch's first two chapters. In the second part, you can write about two or three of your "talismans" so far -- those poems which speak most deeply or mysteriously to your life. I will also suggest five or six additional poets, and you simply write about three of them. |

Your Entry for Monday, March

13: __ In an entry you may choose to react to the poet April Bernard -- like Anne's reaction in the public folder -- or choose one of the poems from Edward Hirsch's Chapter Two in How to Read a Poem .... and Fall in Love with Poetry. The three poems in the chapter are by Elizabeth Bishop, Pablo Neruda, and Jir� Orten. If you have time, you may choose to do both. 15. (Bishop, Neruda or Orten) // (Your Title) or 15. April Bernard // (Your Title) Please also take time to read Hirsch's close reading of the poem you have chosen and weave into your explication some brief commentary on his reading. Pictures and brief biographies of Bishop, Neruda and Orten are most welcome! |

| Here are our two reading groups

Please let me know if the following credit registrations are incorrect... |

Scott Williams 0 |

|

Theme 3 -- Poems about War and Political Engagement

|

Reading for Wednesday,

March 15: __ Read the poems by Celan, Sachs and Akhmatova. These are in the Pinter Anthology on the pages indicated. Writing for Wednesday: 16. Poet's Name // Your Title __ Your first draft of a 3-5 page paper on a Vintage poet is due Friday, March 17 before you go home (at least three of the poet's poems will be featured in your paper). This should be submitted both in hard copy and by e-mail. 17. Poet's Name // Your Term Paper Title

|

| Paul Celan Paul Celan was born in Czernovitz, in Romania, in 1920. Until 1918, this region of Romania had formed part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, a polyglot amalgam of nations stretching from Austria in the west to the Balkans in the south-east. Though each region spoke its own language, and many Jewish communities spoke Yiddish, German acted as the common language for the empire as a whole. The speaking of a good German marked an individual as both bourgeois and cultured, one who particpated in the cosmopolitan world of politics, art, literature and music. Celan grew up speaking German at home and Romanian at school. He also understood Yiddish. His father's interest in Zionism (the movement dedicated to the refounding of a Jewish homeland in Palestine) led to three year's education in a Hebrew school. Later he became fluent in French, Russian and Ukranian. A schoolfriend of Paul Celan wrote, 'We had no natural language. To speak good German was something you had to achieve. You could do it, but it didn't come of itself.' (John Felstiner, Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew (New Haven 1995), p. 6) However, German began as, and remained, his dominant language, in part through the insistence of his mother and her influence on his education. The first poet Celan remembered reading was Schiller and he wrote his first known poems, as a teenager, in German. German was both his mother's gift to him, which had made him a poet, and the weapon that killed her. The Germans deported his parents to labor camps in the Ukraine (ironically the region from which much of Romania's 20th century Jewish population had fled in the nineteenth century to escape brutal pogroms) in the summer of 1942. Neither survived more than a few months. Celan's father died of typhus: the Germans shot his mother that winter as unfit for work. Celan himself worked in several Jewish labor battalions before the Russians liberated Romania in 1944. Unwilling to live under Russian domination, or the communism towards which Romania moved in the 1940s, Celan moved first to Vienna, the one-time capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and then to Paris. Yet, though he could not live in a German-speaking culture, Celan could write in no other language. In 1948, just after he arrived in Paris, he wrote, "There's nothing in the world for which a poet will give up writing, not even when he is a Jew and the language of his poems is German.' (Felstiner, Paul Celan, p. 56) Dennis Schmidt calls German 'the language of his [Paul Celan's] deferred death.' Schmidt goes on to say that Celan's language is forced to "nourish itself...on words that have turned to 'black milk,' 'ash,' and the taste of cyanide on the tongue, 'bitter almonds,' by having been made serviceable for death." (Dennis Schmidt, Black Milk and Blue in Aris Fioretis, ed. Word Traces (Baltimore 1994), p. 114. German thus represented both death and Celan's only hope of communicating the horror through which European Jewry had lived. In the nearly thirty years that he wrote as a mature poet, Celan developed a German all his own, creating many more, and many less immediately comprehensible, metaphoric compounds like Deathfugue. The vocabulary of the German implicated in the Holocaust was inadequate, for Celan, to the task of expressing the agony of extermination. The creativity of his language and its metaphorical density became acts of defiance against the German that had executed his parents and the many millions like them. In his hands, language broke apart on the wheel of history and reformed in poetry. |

|

http://polyglot.lss.wisc.edu/german/celan/gallery.html

|

These first two paintings are called "Black Milk," (Schwarze

Milch). The third painting is titled "Sulamith."

Nelly Sachs, "Landscape of Screams"

Nelly Sachs (1891-1970), daughter of a

wealthy manufacturer, grew up in a fashionable area of Berlin. She studied music and

dancing and at an early age began writing poetry. After her escape to Sweden in 1940, Miss

Sachs took up the study of Swedish and devoted much of her time to the translation of such

Swedish poets as Gunnar Ekel�f, Johannes Edfelt, and Karl Vennberg.

Nelly Sachs's career as a poet of note started only after her

emigration, when she was nearly fifty years old. Her first volume of poetry, In den

Wohnungen des Todes (In the Houses of Death), 1947, creates a cosmic frame for the

suffering of her time, particularly that of the Jews. Although her poems are written in a

keenly modern style, with an abundance of lucid metaphors, they also intone the prophetic

language of the Old Testament. The collections Sternverdunkelung (Eclipse of

Stars), 1949, Und niemand weiss weiter (And No One Knows Where to Go), 1957, and Flucht

und Verwandlung (Flight and Metamorphosis), 1959, repeat, develop, and reinforce the

cycle of suffering, persecution, exile, and death which characterizes the life of the

Jewish people, and becomes transformed, in Nelly Sachs's powerful metaphorical language,

into the terms of man's bitter, but not hopeless, destiny. Of her poetic dramas, the

miracle play Eli (1950), broadcast in West Germany as a radio play, has been widely

acclaimed. Nelly Sachs has received awards in Sweden and Germany, among them the Prize of

the Swedish Poets Association (1958) and the "Friedenspreis des deutschen

Buchhandels" (1965). In 1961 her collected poems were published under the title of Fahrt

ins Staublose (Journey to the Beyond); her verse dramas in Zeichen im Sand

(Signs in the Sand). O the Chimneys, English translations of some of her poetry and

of her play Eli, appeared in 1967.

NOTE: Only nine women have received

(1901-1997) the Nobel Prize for Literature: Selma Lagerl�f, Sigrid Undset, Grazia Deledda, Pearl S.Buck, Gabriela Mistral, Nelly Sachs, Toni Morrison, Nadine Gordimer, Wislawa Szymborska

Anna Akhmatova, "I am not among those who left our land"

Akhmatova, Anna, pseudonym of ANNA ANDREYEVNA GORENKO

(b. June 11 [June 23, New Style], 1889, Bolshoy Fontan, near Odessa, Ukraine, Russian

Empire--d. March 5, 1966, Domodedovo, near Moscow), Russian poet recognized at her death

as the greatest woman poet in Russian literature.

Akhmatova began writing verse at the age of 11 and at 21 became a

member of the Acmeist group of poets, whose leader, Nikolay Gumilyov, she married in 1910

but divorced in 1918. The Acmeists, through their periodical Apollon ("Apollo";

1909-17), rejected the esoteric vagueness and affectations of Symbolism and sought to

replace them with "beautiful clarity," compactness, simplicity, and perfection

of form--all qualities in which Akhmatova excelled from the outset. Her first collections,

Vecher (1912; "Evening") and Chyotki (1914; "Rosary"), especially the

latter, brought her fame. While exemplifying the best kind of personal or even

confessional poetry, they achieve a universal appeal deriving from their artistic and

emotional integrity. Akhmatova's principal motif is love, mainly frustrated and tragic

love, expressed with an intensely feminine accent and inflection entirely her own.

Later in her life she added to her main theme some civic,

patriotic, and religious motifs but without sacrifice of personal intensity or artistic

conscience. Her artistry and increasing control of her medium were particularly prominent

in her next collections: Belaya staya (1917; "The White Flock"), Podorozhnik

(1921; "Plantain"), and Anno Domini MCMXXI (1922). This amplification of her

range, however, did not prevent official Soviet critics from proclaiming her

"bourgeois and aristocratic," condemning her poetry for its narrow preoccupation

with love and God, and characterizing her as half nun and half harlot. The execution in

1921 of her former husband, Gumilyov, on charges of participation in an anti-Soviet

conspiracy (the Tagantsev affair) further complicated her position. In 1923 she entered a

period of almost complete poetic silence and literary ostracism, and no volume of her

poetry was published in the Soviet Union until 1940. In that year several of her poems

were published in the literary monthly Zvezda ("The Star"), and a volume of

selections from her earlier work appeared under the title Iz shesti knig ("From Six

Books"). A few months later, however, it was abruptly withdrawn from sale and

libraries. Nevertheless, in September 1941, following the German invasion, Akhmatova was

permitted to deliver an inspiring radio address to the women of Leningrad [St.

Petersburg]. Evacuated to Tashkent soon thereafter, she read her poems to hospitalized

soldiers and published a number of war-inspired lyrics; a small volume of selected lyrics

appeared in Tashkent in 1943. At the end of the war she returned to Leningrad, where her

poems began to appear in local magazines and newspapers. She gave poetic readings, and

plans were made for publication of a large edition of her works.

In August 1946, however, she was harshly denounced by the Central

Committee of the Communist Party for her "eroticism, mysticism, and political

indifference." Her poetry was castigated as "alien to the Soviet people,"

and she was again described as a "harlot-nun," this time by none other than

Andrey Zhdanov, Politburo member and the director of Stalin's program of cultural

restriction. She was expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers; an unreleased book of her

poems, already in print, was destroyed; and none of her work appeared in print for three

years.

Then, in 1950, a number of her poems eulogizing Stalin and Soviet

communism were printed in several issues of the illustrated weekly magazine Ogonyok

("The Little Light") under the title Iz tsikla "Slava miru"

("From the Cycle 'Glory to Peace' "). This uncharacteristic capitulation to the

Soviet dictator--in one of the poems Akhmatova declares: "Where Stalin is, there is

Freedom, Peace, and the grandeur of the earth"--was motivated by Akhmatova's desire

to propitiate Stalin and win the freedom of her son, Lev Gumilyov, who had been arrested

in 1949 and exiled to Siberia. The tone of these poems (those glorifying Stalin were

omitted from Soviet editions of Akhmatova's works published after his death) is far

different from the moving and universalized lyrical cycle, Rekviem ("Requiem"),

composed between 1935 and 1940 and occasioned by Akhmatova's grief over an earlier arrest

and imprisonment of her son in 1937. This masterpiece--a poetic monument to the sufferings

of the Soviet peoples during Stalin's terror--was published in Moscow in 1989.

In the cultural "thaw" following Stalin's death,

Akhmatova was slowly and ambivalently rehabilitated, and a slim volume of her lyrics,

including some of her translations, was published in 1958. After 1958 a number of editions

of her works, including some of her brilliant essays on Pushkin, were published in the

Soviet Union (1961, 1965, two in 1976, 1977); none of these, however, contains the

complete corpus of her literary productivity. Akhmatova's longest work, Poema bez geroya

("Poem Without a Hero"), on which she worked from 1940 to 1962, was not

published in the Soviet Union until 1976. This difficult and complex work is a powerful

lyric summation of Akhmatova's philosophy and her own definitive statement on the meaning

of her life and poetic achievement.

Akhmatova executed a number of superb translations of the works

of other poets, including Victor Hugo, Rabindranath Tagore, Giacomo Leopardi, and various

Armenian and Korean poets. She also wrote sensitive personal memoirs on Symbolist writer

Aleksandr Blok, the artist Amedeo Modigliani, and fellow Acmeist Osip Mandelstam.

In 1964 she was awarded the Etna-Taormina prize, an international

poetry prize awarded in Italy, and in 1965 she received an honorary doctoral degree from

Oxford University. Her journeys to Sicily and England to receive these honours were her

first travel outside her homeland since 1912. Akhmatova's works were widely translated,

and her international stature continued to grow after her death. A two-volume edition of

Akhmatova's collected works was published in Moscow in 1986, and The Complete Poems of

Anna Akhmatova, also in two volumes, appeared in 1990.

"War has been given a bad name."

"War has been given a bad name."

original name EUGEN BERTHOLD FRIEDRICH BRECHT

Biographical information from http://www.cs.brandeis.edu/~jamesf/goodwoman/brecht_bio.html

(b. Feb. 10, 1898, Augsburg, Ger.--d. Aug. 14, 1956, East Berlin),

German poet, playwright, and theatrical reformer whose epic theatre departed from the

conventions of theatrical illusion and developed the drama as a social and ideological

forum for leftist causes.

Until 1924 Brecht lived in Bavaria, where he was born, studied medicine (Munich, 1917-21), and served in an army hospital (1918). From this period date his first play, Baal (produced 1923); his first success, Trommeln in der Nacht (Kleist Preis, 1922; Drums in the Night); the poems and songs collected as Die Hauspostille (1927; A Manual of Piety, 1966), his first professional production (Edward II, 1924); and his admiration for Wedekind, Rimbaud, Villon, and Kipling.

During this period he also developed a violently antibourgeois attitude that reflected his generation's deep disappointment in the civilization that had come crashing down at the end of World War I. Among Brecht's friends were members of the Dadaist group, who aimed at destroying what they condemned as the false standards of bourgeois art through derision and iconoclastic satire. The man who taught him the elements of Marxism in the late 1920s was Karl Korsch, an eminent Marxist theoretician who had been a Communist member of the Reichstag but had been expelled from the German Communist Party in 1926.

In Berlin (1924-33) he worked briefly for the directors Max Reinhardt and Erwin Piscator, but mainly with his own group of associates. With the composer Kurt Weill (q.v.) he wrote the satirical, successful ballad opera Die Dreigroschenoper (1928; The Threepenny Opera) and the opera Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (1930; Rise and Fall of the Town of Mahoganny). He also wrote what he called "Lehr-stucke" ("exemplary plays")--badly didactic works for performance outside the orthodox theatre--to music by Weill, Hindemith, and Hanns Eisler. In these years he developed his theory of "epic theatre" and an austere form of irregular verse. He also became a Marxist.

In 1933 he went into exile--in Scandinavia (1933-41), mainly in Denmark, and then in the United States (1941-47), where he did some film work in Hollywood. In Germany his books were burned and his citizenship was withdrawn. He was cut off from the German theatre; but between 1937 and 1941 he wrote most of his great plays, his major theoretical essays and dialogues, and many of the poems collected as Svendborger Gedichte (1939). The plays of these years became famous in the author's own and other productions: notable among them are Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (1941; Mother Courage and Her Children), a chronicle play of the Thirty Years' War; Leben des Galilei (1943; The Life of Galileo); Der gute Mensch von Sezuan (1943; The Good Woman of Setzuan), a parable play set in prewar China; Der Aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui (1957; The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui), a parable play of Hitler's rise to power set in prewar Chicago; Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti (1948; Herr Puntila and His Man Matti), a Volksstuck (popular play) about a Finnish farmer who oscillates between churlish sobriety and drunken good humour; and The Caucasian Chalk Circle (first produced in English, 1948; Der kaukasische Kreidekreis, 1949), the story of a struggle for possession of a child between its highborn mother, who deserts it, and the servant girl who looks after it.

Brecht left the United States in 1947 after having had to give evidence before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He spent a year in Zurich, working mainly on Antigone-Modell 1948 (adapted from Hulderlin's translation of Sophocles; produced 1948) and on his most important theoretical work, the Kleines Organon fur das Theater (1949; "A Little Organum for the Theatre"). The essence of his theory of drama, as revealed in this work, is the idea that a truly Marxist drama must avoid the Aristotelian premise that the audience should be made to believe that what they are witnessing is happening here and now. For he saw that if the audience really felt that the emotions of heroes of the past--Oedipus, or Lear, or Hamlet--could equally have been their own reactions, then the Marxist idea that human nature is not constant but a result of changing historical conditions would automatically be invalidated. Brecht therefore argued that the theatre should not seek to make its audience believe in the presence of the characters on the stage--should not make it identify with them, but should rather follow the method of the epic poet's art, which is to make the audience realize that what it sees on the stage is merely an account of past events that it should watch with critical detachment. Hence, the "epic" (narrative, nondramatic) theatre is based on detachment, on the Verfremdungseffekt (alienation effect), achieved through a number of devices that remind the spectator that he is being presented with a demonstration of human behaviour in scientific spirit rather than with an illusion of reality, in short, that the theatre is only a theatre and not the world itself.

In 1949 Brecht went to Berlin to help stage Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (with his wife, Helene Weigel, in the title part) at Reinhardt's old Deutsches Theater in the Soviet sector. This led to formation of the Brechts' own company, the Berliner Ensemble, and to permanent return to Berlin. Henceforward the Ensemble and the staging of his own plays had first claim on Brecht's time. Often suspect in eastern Europe because of his unorthodox aesthetic theories and denigrated or boycotted in the West for his Communist opinions, he yet had a great triumph at the Paris Theatre des Nations in 1955, and in the same year in Moscow he received a Stalin Peace Prize. He died of a heart attack in East Berlin the following year.

Brecht was, first, a superior poet, with a command of many styles and moods. As a playwright he was an intensive worker, a restless piecer-together of ideas not always his own (The Threepenny Opera is based on John Gay's Beggar's Opera, and Edward II on Marlowe), a sardonic humorist, and a man of rare musical and visual awareness; but he was often bad at creating living characters or at giving his plays tension and shape. As a producer he liked lightness, clarity, and firmly knotted narrative sequence; a perfectionist, he forced the German theatre, against its nature, to underplay. As a theoretician he made principles out of his preferences--and even out of his faults.

| For Friday, March 17: __ Write a brief entry on Celan, Sachs, or Bertold Brecht's "War has been given a bad name."

18. Celan, Brecht or Sachs // Your Title __ Your completed first draft about a Vintage Poet's works. 17. Poet's Name // Your Term Paper Title

|

|

| Blok, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich http://webserver.rcds.rye.ny.us/id/poetry/Lindsay'spoetrypage.html

(small pic above and bio). Blok, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich (1880-1921), Russian poet, the leader of Russian symbolism, a counterpart of the European literary movement (see Symbolist Movement) strongly influenced by the Eastern Orthodox faith. He was born in Saint Petersburg and educated at Petersburg University. Blok's early cycle of mystical love poems Stikhi o prekrasnoy dame (Verses About the Lady Beautiful, 1904) equated divine wisdom with the feminine soul. Thereafter, as in Neznakomka (The Unknown Woman, 1906), his poetry took on a darker, pessimistic tone, but even his most melancholy works display his characteristic lilting musicality. In 1917 the Russian Revolution gave him new hope, and he turned against what he perceived as the sterile intellectuality of symbolism. Skify (1918; The Scythians, 1920), an ode alternately passionate and melancholy, expresses his faith in Russia's victory over the West. His last and most famous work, Dvenadtsat (1918; The Twelve, 1920), is a more ambiguous expression of this hope. In the last years of his life, however, he became disenchanted because of the Soviet requirement that authors express party views rather than individual feelings.  http://www.litera.ru:8085/stixiya/authors/blok.html

(pic) http://www.litera.ru:8085/stixiya/authors/blok.html

(pic)

|

__ Read through and thoroughly annotate the rest of the War poems from your Pinter Anthology (see matrix below for titles and page numbers). __ Prepare to discuss in class "The Vulture" by Aleksandr Blok on page 23 of the Pinter Anthology. (The only writing assignment will be your annotations, questions and creative insights. Simply jot them in your book to prepare for discussion.) __ The second half of class you will meet in your presentation groups to brainstorm ideas about how to present your Vintage author and her or his poems in an imaginative way. Presentations start on Thursday. Check with your presentation partner(s) if you have a question about the date of your presentaiton. |

Poems to have read and annotated by Tuesday, March 28.

Source |

POET |

DATE - poet or poem |

POEM |

War, Engagement Political |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 31 | Celan, Paul | 1920-1970 | Deathfugue | Death of Jews in concentration camp |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 110 | Sachs, Nelly | 1891-1970 | Landscape of Screams | History of Screams OT + CT. Knife into throats. Silences. Ashen (like Celan's Death Fugue |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 115 | Segalen, Victor | 1878-1919 | Mongol Libation | Libation is Drink in Awe at courage of opponent: "Do us the honor of being reborn among us." |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 1 | Akhmatova, Anna | 1889-1966 | I am not among those who left our land | Rage at new dictatorship |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 99 | Prevert, Jacques | 1900-1977 | Pater Noster | ironic celebration of earth's wonders GOD beauty vs EARTH misery... Our Father who art in heaven / Stay there .. (beauty of the earth) with the straw of misery rotting in the steel / of cannons. |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 63 | Levi, Primo | 1919-1987 | Shema | Grief at war, nazi camps. Ausschwitz at 24. CURSE. VOICE. GRIEF. You who live secure / In your warm houses ... Consider whether this is a man (woman) ... may your house crumble / disease render you powerless / ... |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 108 | Ritsos, Yannis | 1909-1990 | Search | His house being searched - hatred of Greek dictatorship - murder of loved one? |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 49 | Jouve, Jean Jouve | 1887-1976 | We have amazed by our great sufferings | Sufferings of war brings the cosmic horsemen of the last judgement. We have become ... the caterpillar horsemen / Of the last judgment. (Hitler, Fascism, second coming. |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 23 (Prepare this one thoroughly for Tuesday's class discussion) | Blok, Aleksandr | 1880-1921 | The Vulture | How long must the mother wail? / How long must the vulture wheel? ( Woman's perspective.) Vulture and mother - what do they represent? |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 24 | Brecht, Bertolt | 1898-1956 | War has been given a bad name | "The way it has been conducted on this occasion" |

| *Pinter 99 Poems 18 | Aragon, Louis | 1897-1982 | The Lilacs and the Roses | I shall never forget the bouquets of lilacs (going to war) nor the bouquets of roses (retreating from war). |

| For Thursday, March 30: ___ Read the poems in Edward Hirsch's Chapter Two How to Read a Poem .... and Fall in Love with Poetry by Elizabeth Bishop, Pablo Neruda, or Jir� Orten -- and write an entry on ONE of the poems. If you find an image on your poet on the web, please include that. Choose and quote specific words or phrases for your explication. Include some discussion about Hirsch's ideas concerning your poem, especially insights you found most helpful. 19. (Bishop, Neruda or Orten) // (Your Title) __ Read the poetry of Taslima Nasrin, Vintage Anthology, pp. 401-405, and also the following information supplied by Ann, Jeff, Jenn and Tim to prepare for the presentation in class by |

Taslima Nasrin http://www.humanists.net/nasrin/poetry_by_taslima_nasrin.htm

Taslima Nasrin http://www.humanists.net/nasrin/poetry_by_taslima_nasrin.htm

The poem "Border" differs significantly from "Happy Marriage" in the means by which the wife comes to terms with her husband's dominion over her. In "Border," the speaker is restrained by her husband forbidding her to escape, but also by her duties as a mother and as the nurturer of the family. She realizes that escape will not be easy; she sees it as being quite an obstacle, but she has confidence in her ability to survive and make it on her own. In the first stanza she compares the hardships she must conquer to a river that must be crossed, but despite the fact that she knows she can do it, her family ". . . won't let me swim, won't let me cross" (Wright 19).

In the second, third, and fourth stanzas, the speaker

discusses the freedoms that await her on the other side of the "river;" she

revels in the notions of being able to do things she has not done in years, since her

youth. She first discusses dancing in an open space, and enjoying the freedom of a vast

field, alone--she looks to the future and resolves to someday dance in that open space.

Next, she addresses the idea of "playing keep-away," something she once did as a

child. She is determined to ". . . raise a great commotion playing keep-away

someday." Finally she confesses that she has not cried out of loneliness in a long

time, and once again she promises to cry. In each of these instances, she makes a promise

to go across, find some freedom, and "return."

In the final stanza, she looks ahead at the "river" and to the possibilities

that await her on the other side. Nasrin ends the poem with the line "Why shouldn't I

go? I'll go." The ending of the poem gives the reader a great sense of hope for the

speaker -- she realizes her oppressed state and desires to get out of it; she knows she

has the capabilities to do so; she also knows her responsibilities to her family, but she

does not let that stand in the way of achieving the freedom she has promised herself. This

concern for the self is something refreshing that is found in Nasrin's poetry--according

to the traditional expectations and values of South Asian society, women are constantly

expected to sacrifice their own personal freedom and happiness for the sake of husbands,

children, and family. However, through the poem "Border," Nasrin reaffirms the

woman as a human being who has duties and responsibilities to her family, but is also

worthy of satisfying her own desires and aspirations. http://www.emory.edu/ENGLISH/Bahri/Nasrin.html

| Jen, Jeff, Ann and Tim (Nasrin) bravo!

brava!

Whatever pictures and biographical information or quotes you would like to supply

by e-mail ahead of time, it will be posted here. |

For Monday, April 3: __ Write a brief entry about the presentation given by Jen, Tim, Ann and Jeff on Taslima Nasrin. Include at least one or two quotes from the poetry they covered. How do you know and understand this poet better after their presentation? What aspects of how they taught the poet were particularly effective? 20. Jeff, Ann, Jen and Tim // Nasrin Presentation // Your Title __ Write a brief entry on one of the poems by Dahlia Ravikovitch or Ryuichi Tamura which will be presented next time. (Pinter Anthology, pp. 329ff and 457ff, respectively). 21. Ravikovitch or Tamura // Your Title

|

Go to

Daisy Zamora

(This table if for Fr. Mark's reference)

|