CO22. Conjugate Addition

Conjugated systems are structures that contain alternating double and single bonds (or, in some cases, a double bond that is next to an atom with either a lone pair or a vacant orbital). Conjugated systems are usually at lower energy than regular double bonds because the electrons involved in bonding are delocalized; they are spread out over a greater area and thus can have a longer wavelength.

Figure CO22.1. A conjugated ketone or enone.

For example, the -bonding system for 3-butene-2-one (or methyl vinyl ketone) is described by orbitals involving both the carbonyl group and the alkene group. These two groups become linked together so that there is not longer an independent carbonyl nor an independent alkene, but one "enone" (a term taken from the words alkene and ketone).

Figure CO22.2. Frontier molecular orbitals for an enone.

Because of that extra stability, it might not be surprising that conjugated carbonyls are often a little slower to react than regular carbonyls. The surprise is that conjugated carbonyls can sometimes give additional products in which addition does not take place at the carbonyl.

Figure CO22.3. A conjugate addition.

The product shown above is called a conjugate addition product, or a 1,4-addition product. In conjugate addition, the nucleophile does not donate to the carbonyl, but instead donates to an atom that is involved in conjugation with the carbonyl. This additional electrophilic position is sometimes called a "vinylogous" position (from the word vinyl, which refers to that CH=CH2 unit next to the carbonyl).

-

Conjugate additions (or 1,4-additions) can occur when a carbonyl is attached to a C=C bond.

Problem CO22.1.

Draw a mechanism with curved arrows for the conjugate addition shown above.

Problem CO22.2.

Regular additions to carbonyls are sometimes called 1,2-additions, whereas conjugate additions are called 1,4-additions. Show why.

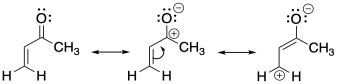

Remember that we can look at another resonance structure of a carbonyl, one that emphasizes the electron-poverty of the carbonyl carbon. It's not a good Lewis structure because of the lack of an octet on carbon, but it does reinforce the idea that there is at least some positive charge at that carbon because it is less electronegative than oxygen. Extending that idea, we can draw an additional resonance structure in a conjugated system. That third structure suggests there may be some positive charge two carbons away from the carbonyl, on the β position on the double bond.

Figure CO22.4. Resonance structures of an enone.

The idea that there are two electrophilic positions in an enone is reinforced by the picture of the LUMO (the lowest-energy "empty" frontier orbital, the virtual place where an additional electron would probably go). When a lone pair is donated to an electrophile, the electrons are most likely to be donated into the LUMO.

Figure CO22.5. A more accurate picture of the LUMO of an enone.

Although it isn't obvious from the cartoons we often draw for molecular orbitals, quantum mechanical calculations suggest that the LUMO is "larger" at the carbonyl position as well as the β-position on the vinyl group.

How can it be larger on some atoms than others? A molecular orbital is an algebraic combination of atomic orbitals. In this case,

LUMO = apC1 + bpC2 + cpC3 + dpO

in which pC1 is the p orbital on the carbon on the left, pO is the p orbital on the oxygen, and so on. The letters a, b, c and d are just numbers; they are the coefficients in the equation. The result of the molecular orbital calculation in this case suggests that the numbers a and c are a little bigger than b and d. Incidentally, it also suggests that a and d have opposite sign from b and c (maybe a and d are positive numbers whereas b and c are negative numbers), meaning that a and d are out of phase with b and c.

In any case, we sometimes think of the large LUMO on particular atoms as being an easier "target", an easier place to throw the incoming electrons. These mathematical results really just reflect what we would expect from the resonance structures.

Problem CO22.3.

Indicate whether the following systems are capable of undergoing conjugate addition, and show why or why not.

Having two possible products of a reaction can be confusing. How do you know which one will result? Often, you don't know. Frequently, both products result, so there is a mixture of commpounds. However, one product often predominates. In conjugate addition, there are a few different factors that may tilt the reaction in one direction or another.

Possibly the simplest reason is steric effects. Maybe one of the electrophilic positions is more crowded than the other, and the nucleophile can access that position more easily.

-

Addition of a nucleophile often occurs at the least crowed electrophile.

Figure CO22.6. Steric crowding in direct vs. conjugate addition.

Problem CO22.4.

In each of the following cases, indicate whether the addition of a nucleophile will be via 1,2-addition, via 1,4-addition, or an equal mixture.

The hard/soft acid characteristics of the two electrophilic positions also influence the reaction. The carbonyl position is closer to the oxygen, of course, and it makes sense that the oxygen would have a greater influence on this carbon. The carbonyl position, with its more concentrated positive charge, is a harder electrophile. The vinylogous position, with less positive charge, is a softer electrophile.

Figure CO22.7. Hard and soft characteristics of an enone.

-

Carbonyls are hard electrophiles.

-

Vinylogous positions are soft electrophiles.

Soft nucleophiles are more likely to react with soft electrophiles, and hard nucleophiles are more likely to react with hard electrophiles. The amount of negative charge concentrated at the nucleophilic atom is the biggest factor determining hardness. The lower the charge, or the more spread out the charge, the softer the nucleophile.

There are a couple of common factors that can influence the amount of charge at the nucleophile. One of them is simply whether there is charge at all: a neutral nucleophile like an alcohol, an amine, an or a thiol is relatively soft. They are not equally soft; the alcohol is the hardest of the three and the thiol is the softest. All three are capable of undergoing conjugate addition with enones. Another factor is conjugation, which spreads out the charge. Conjugated nucleophiles tend to be softer. Also, the electronegativity of the attached atom can be important in a semi-anionic nucleophile. A less electronegative lithium or magnesium atom makes for a harder carbon nucleophile in a Grignard or alkyllithium reagent, compared to when the alkyl is bonded to some other metals. Notably, copper is more electronegative than magnesium or lithium, and so alkylcopper compounds are softer nucleophiles than Grignards and alkyllithiums.

Problem CO22.5.

Indicate whether the following nucleophiles are more likely to undergo 1,2-addition or 1,4-addition.

There are other factors that play roles in influencing the course of these reactions. Sometimes the mechanism of reaction is slightly different under different circumstances. The presence of Lewis acid catalysts can also influence reactivity in these systems, but not always in a predictable way. In most cases, the presence of a Lewis acid makes the addition more likely to proceed in a 1,4-fashion through a mechanism that involves polarization of the conjugate position. However, there are a few more complicated cases in which an interaction between the Lewis acid and the nucleophile ends up delivering the nucleophile to the regular carbonyl position.

Figure CO22.8. Lewis acid activation of an enone.

-

Lewis acid catalysts can influence whether a reaction proceeds via 1,4-addition.

Problem CO22.6.

Fill in the products of the following reactions.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted on individual pages. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and

Inorganic Chemistry by

Chris Schaller is licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation:

Back to Carbonyl Addition Index

Back to Web Materials on Structure & Reactivity in Chemistry