Reactivity in Chemistry

Aliphatic Nucleophilic Substitution

NS16. Nucleophilic Substitution in Synthesis: Alcohols and Ethers

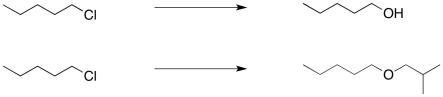

Nucleophilic substitution reactions can be useful in organic synthesis. Mostly they are used for the interconversion of functional groups. For example, an alkyl halide might be transformed into an alcohol, or into an ether.

Figure NS16.1. Formation of alcohols and ethers from haloalkanes.

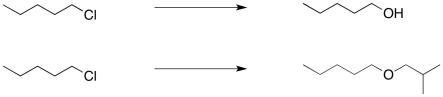

The trouble is, these seemingly simple steps can be very difficult. That's because the hydroxide needed to make an alcohol from an alkyl halide is really quite basic. So is the alkoxide that would be needed in order to turn an alkyl halide into an ether. Instead of substitution, you may get an elimination reaction.

Figure NS16.2. Complications in the formation of alcohols and ethers from haloalkanes.

Who cares? Well, you would care if you were working on the synthesis of an antimalarial drug that could save millions, or an anticancer drug, or anything of that nature. Maybe that ether forms the last crucial part of the pharmacophore that will bind the drug to its target. Without this reaction, it may be thousands of times less effective. So this little reaction could be very important.

Clearly, the best thing to do would be to make sure a substitution reaction happened, and not that elimination. We need the reagent to be a nucleophile, not a base.

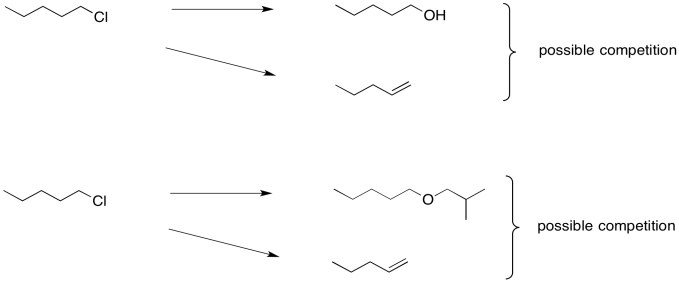

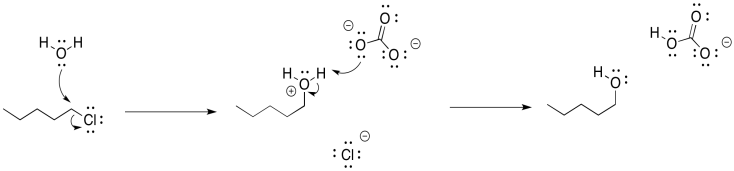

In the case of the alcohol synthesis, we could use water as the nucleophile, rather than hydroxide. Water is certainly less basic than hydroxide ion. It is still nucelophilic, though, because it still has a lone pair. If we add it to an alkyl chloride, the water will displace the chloride, and then the extra proton will be plucked off the positive oxygen atom by the chloride, leaving us with the alcohol.

Figure NS16.3. Formation of an alcohols from a haloalkane under weakly basic conditions.

That last step would form hydrogen chloride, a corrosive acid, and that could cause problems. To counteract that possibility, we will want to add a weak base so that the HCl gets neutralized. Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) or sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) may be good options, because they are mildly basic and they dissolve in water.

Figure NS16.4. The role of the weak base in carbonate-mediated formation of an alcohol.

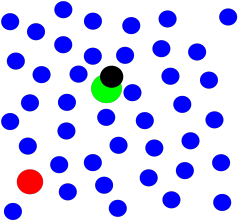

Alternatively, we could just use sodium hydroxide as the base. That gets us back to the original problem. However, in order to avoid elimination, we would use very dilute sodium hydroxide. We would keep its concentration low enough that the alkyl halide is much more likely to react with the water than with the hydroxide ion, for the simple reason that it is much more likely to run into a water molecule than a hydroxide ion. However, once that oxygen donor atom picked up a positive charge, it would be more attractive to the hydroxide ion, and the hydroxide would then come in for the proton.

Figure NS16.5. The role of dilution in changing the mechanism of elimination.

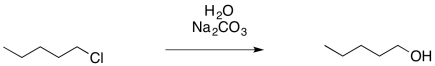

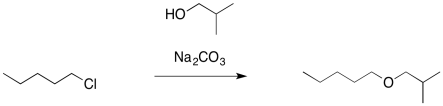

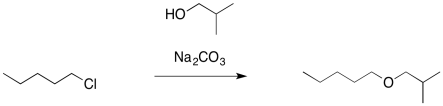

In the same way, if we wanted to make an ether, but the standard Williamson approach was causing problems, we could try another approach. We might use an alcohol as the nucleophile rather than the much more basic alkoxide ion. We would add a weak base to sponge up the extra proton and avoid formation of a strong acid.

Figure NS16.6. The use of a weak base in ether formation.

Problem NS16.1.

Provide a mechanism for the following reaction.

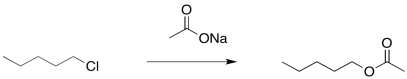

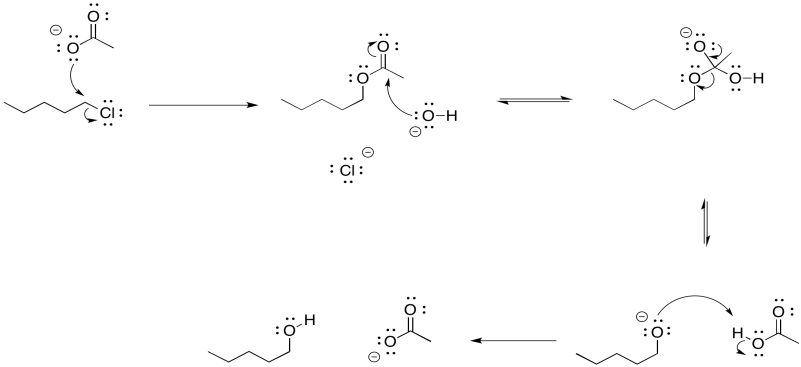

There is another approach to limiting the amount of elimination during a substitution step to form an alcohol. It also involves the use of a more stable nucleophile than a hydroxide ion. However, it employs a more reactive anionic nucleophile, rather than the neutral water. If an acetate ion is used instead, very little elimination usually occurs. An ester is formed as a product. There isn't much elimination because the acetate ion is resonance stabilised. More stable nucleophiles often undergo substitution rather than elimination.

Figure NS16.7. Formation of an acetate from an alkyl halide.

Of course, we didn't want an ester; we wanted an alcohol. No problem. Esters can be saponified relatively easily -- that is, broken down into an alcohol and a carboxylate. Just add a hydroxide and water. Now the stronger carbonyl electrophile is a better target for the hydroxide and the reaction is pretty well assured to get to the right place.

Figure NS16.8. Saponification of an ester to make an alcohol.

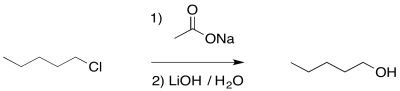

Overall, the reaction is actually a sequence of several events.

Figure NS16.9. Mechanism of alcohol synthesis via an acetate intermediate.

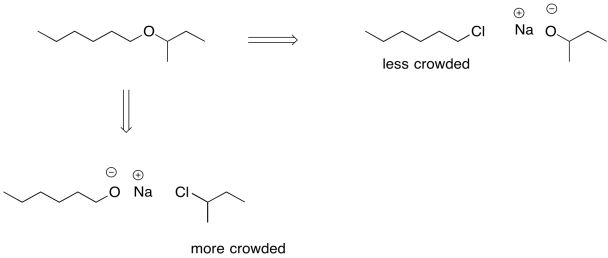

We can't take the same approach in ether synthesis. An ether is an oxygen bridge between two tetrahedral or sp3 carbons; we can't have resonance stabilisation and still have those two sp3 carbons. Instead, another strategy is sometimes employed during addition of an anionic nucleophile to an alkyl halide. An alkoxide ion is still employed, but care is taken in how the alkoxide and the alkyl halide are chosen. Because the ether is symmetric -- it is two tetrahedral carbons attached to an oxygen -- either side could originate as the alkoxide and either side could originate as the alkyl halide.

Figure NS16.10. Retrosynthetic strategies for an ether.

If the alkyl halide is chosen so that steric crowding is minimized, there is a lower chance of an accidental collision between the alkoxide and a beta hydrogen on that alkyl halide. In some cases, we might even be able to choose the alkyl halide so that elimination is not possible at all. If possible, we can use an alkyl halide that doesn't have any beta hydrogens.

Figure NS16.11. Williamson synthesis of an ether.

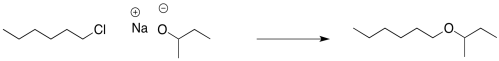

In general, the use of alkoxide ions as nucleophiles can be pretty successful if done carefully, and this approach to making ethers even has its own name. It's called the Williamson ether synthesis.

Problem NS16.2.

Propose Williamson ether syntheses of the following compounds.

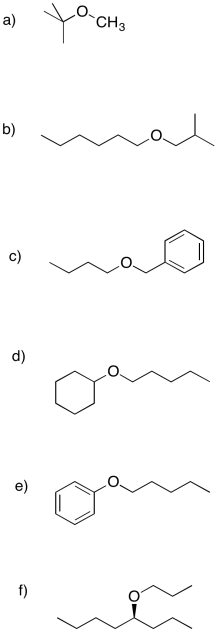

Problem NS16.3.

Provide products of the following reactions.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with other authors as noted). It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Send corrections to cschaller@csbsju.edu

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: